Clemmons Interview on Damn The Machine: Inside the Past, the Present, and the War Within

David Judson Clemmons invites listeners to step into a carefully curated portrait of his artistic life with a set of vinyl releases that span decades of creation.

In collaboration with Village Slut Records and 7 People Records, this series brings together his most recent solo vision, the long awaited return of the Damn The Machine debut, and two archival collections that reveal the band’s earliest creative moments.

At the center is ‘Everything A War,’ Clemmons’ deeply personal statement on a lifetime shaped by reflection, conflict, and hope. Clemmons has long believed in the power of song to inspire and comfort, and this record represents the clearest distillation of that belief. It is music formed by decades of living, learning, and letting sound speak where words cannot.

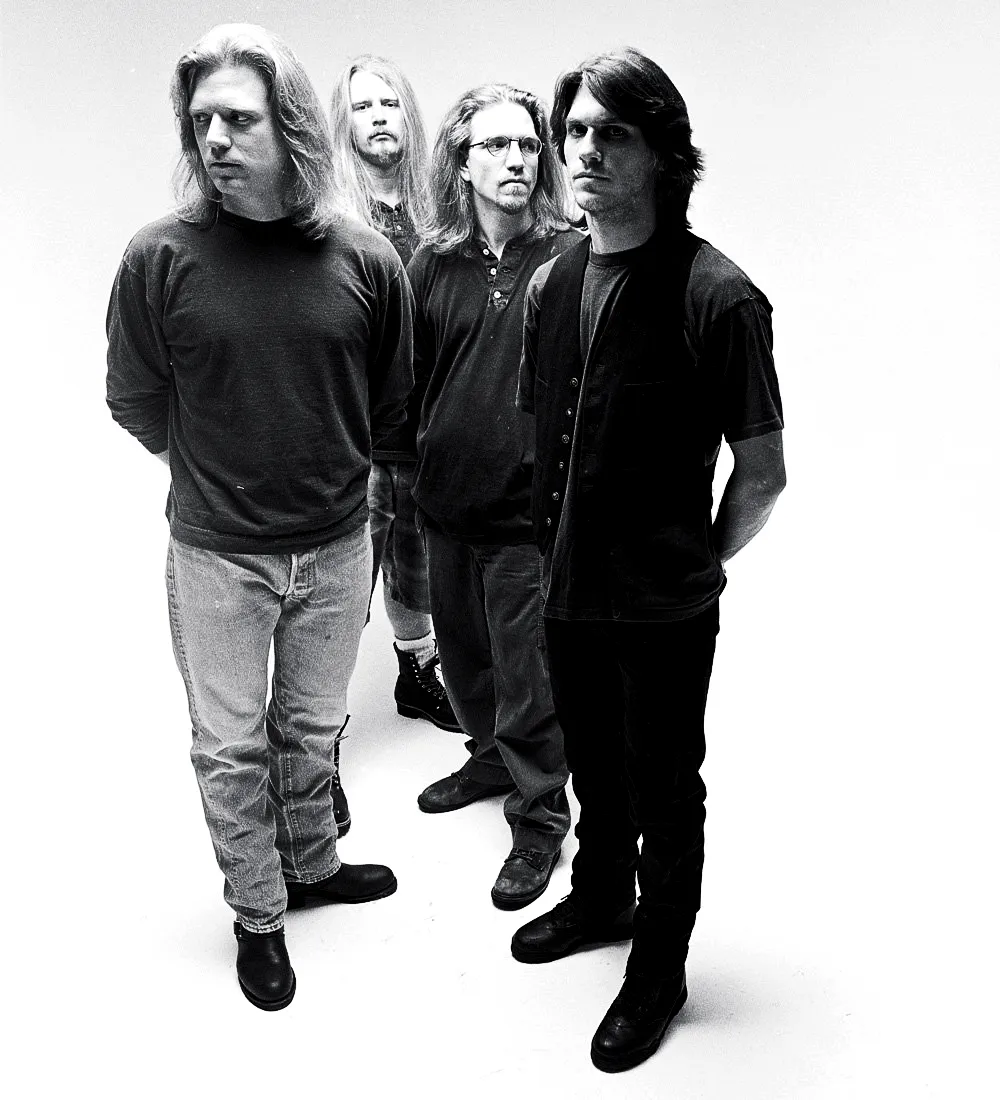

Equally significant is the first ever vinyl edition of Damn The Machine’s seminal debut. Created through an intense and rare creative connection between Clemmons, Chris Poland, Dave Randi, and Mark Poland, the album remains a fearless exploration of form, texture, and emotion.

Completing the collection are’ The Last Man’ and ‘Day One.’ These releases offer an unfiltered window into the earliest days of the band, capturing raw takes, instinctive performances, and the energy of discovery. Together, these records form a time capsule that honors where it began, celebrates what endured, and affirms what is still to come.

“It feels very full circle”

You had this huge October release with three different albums. Your recent solo work, the classic Damn the Machine debut, and those old DTM demos. That is a massive slice of your career. When you look at all of it together, what is the one big story or theme that ties everything from then to now together. Is there a new kind of narrative that pops out at you, seeing it all lined up?

David Judson Clemmons: Well, at first glance, it feels very full circle. What comes to mind is how these two albums, Debut and ‘Everything A War,’ define a certain aspect of my style. At the same time, there were three decades of struggle and about twenty albums in between that all have their own stories to tell. It feels different now than it did in the eighties, but it is almost like it took this period of time in between to complete the sandwich, so to say.

Back when you were making the first ‘Damn the Machine’ album, you and Chris Poland wondered if you were getting too far out and flying over everyone’s heads. Now, more than thirty years later, you are putting it back out there for a new generation. Do you still feel like the music is ahead of its time, or do you think listeners have finally caught up to what you were trying to do?

The combination of styles and influences from Chris and myself definitely showed in our work together. It was a one in a million collision of different perspectives that just harmonized great together. It feels more now like we were steps ahead than it did then, honestly. We were so close to the music in the creation phases back then, really living each part of every song. We would call each other after rehearsals all excited about little things we did that day. We were pushing forward as far as we could, but to see it in an out of body way and judge it back then was not really possible. Now, after a long break, I may have gone ten years without listening to the album, and it is easier to appreciate it.

You called the demo collections, ‘The Last Man’ and ‘Day One,’ a time capsule. When you went back and listened to those super early DTM tracks, what did you rediscover about your younger creative self. Did you hear any cool little bits or ideas that you might have tucked away and later used on your new solo album, ‘Everything A War’?

The styles are so different. DTM writing was coming from a similar place mentally, but it came out more in the form of tight, compact riffs, puzzled nicely together with no empty space. I did discover things in the old recordings, hearing some vocal stuff and guitar work that I had long forgotten, but there was no real connection with my current writing. I have been through a lot over these years, and my newer writing has more than enough fuel to burn. I have never suffered from writer’s block, rather the opposite, so I just enjoyed having the old tapes. That part was really a wonderful thing. But the old recordings mostly showed a raw, energetic, naive side of me that is long gone, more than any inspiration for new material.

Your recent album, ‘Everything A War,’ is a deep look into your whole life’s journey. The title itself suggests a constant fight. It was first released digitally, but now you are putting it out on vinyl, which is a much more solid, physical thing. Does putting it on vinyl feel like it gives the album more weight or a sense of permanence?

Yes, a vinyl release is always more satisfying than a digital release, and I am so glad things developed in a way that made it possible. I have constantly longed for peace, whether in the mind or on the streets, and I ponder over and over how humans can do the things they do. We have conquered so many more difficult problems, and our science has taken us so far, and yet we do the same stupid stuff to each other as since the beginning of civilization, like zero development as a species. This brings me to this title.

You mentioned that with the other guys in Damn the Machine, there was an explosion of creativity. Can you describe what that felt like. Was it like you were all on the same wavelength, or something more. How was that different from working on your solo stuff, where you are probably more in your own head?

It was great to have Mark and Dave Randi there to bring all this guitar mess to life. It was a big soup of sound sometimes. I remember being amazed at how a few guitar parts could develop into such massive songs. We talked a lot during writing, about different rhythm ideas and how to play certain sections to get a vibe that was fresh. It was so much more dynamic and full of air than my solo stuff that I had been doing with Dave McClain in Ministers of Anger. Playing with Chris really opened my mind to how much is possible without just killing the listener with constant pressure. He is a master of guitar dynamic. This is a big part of the DTM sound.

The vinyl releases are all unique. Silver for your solo album, blue and turquoise for the DTM debut, and black and clear for ‘The Last Man’. You clearly put some thought into this. What is the story behind the different colors and designs. Are you trying to give each record its own unique vibe?

Well, I would like to say I really planned that and had a big secret Taylor Swift style meaning behind it, but it was more about what color fits combined with what color the pressing plant had in stock, combined with not duplicating colors on different releases. That is the real truth. For Debut, Chris wanted blue, and I added the turquoise because I thought it was a nice alternative. Now we added purple too, since the CD booklet had purple in it, so we pulled from that a bit. ‘Day One’ in red is awesome. It is so fun to pull that out of the sleeve. That matches the great cover from Chris Corrado, so that was an obvious choice.

You have said that you care most about how your songs might push people in a positive direction. Your music spans everything from intense progressive metal to more laid back singer songwriter tunes. How do you see a positive direction playing out differently for a fan of ‘Damn the Machine’ versus a fan of your solo work?

DTM fans are nice people, mostly, but they are more based in the thrash and guitar god genre. My fans for my personal work are also mostly nice people, but less guitar god based and more song based. People who listen to Nick Cave, Johnny Cash, Townes Van Zandt, Pink Floyd, and Neil Young. So there is some crossover, but also some differences. Mentally, the thought processes are similar. It has always been my goal as a musician to inspire, provoke good thought, and never judge people for who they are or what they believe in. I could never get into that kind of radical stuff. I am a highly focused, super easygoing dude, focused on holding onto positive energy no matter what happens. My idea of a great day is a coffee with the sunrise, a chat with a ninety year old lady at the bus stop, a good riff or two, and a call with an old friend.

Chris Poland joked that he liked the raw demos on ‘Day One’ better than the final album. That is a great line. Looking back, what do you think is the real value of those unpolished, rough recordings. Is there something honest or true in them that sometimes gets lost in a big studio production?

Yes, for sure, but we were insanely over practiced, so parts of the album and demos are hard to tell apart. Still, there is a rawness in the demos that I really love. It is just part of the deal when you get in the studio, especially for me. I was as green as they come. Big producer, big machines, and I had no idea what they even did back then. The difference is there, but we were lucky. Brian Malouf is a great soul and captured us just as he wanted, as live as possible with no multi tracked guitars. The guitars on the debut album are simply Chris on the left and me on the right. Sometimes it switched, but we did not stack any guitars. It is raw and exactly as we played it.

You have been making music since the early nineties, when things were all about major labels and CDs, and now you are in the world of indie releases and streaming. These new vinyl reissues kind of sit in the middle of all that. What is the biggest lesson you have taken away from each era, and how did that influence your decision to partner with Village Slut Records and 7 People Records for this project?

I started my own label in 2004, just after getting tired of waiting around for people to move. I was writing a lot of music and could not get it out fast enough, so I found a great distribution partner and started my own label. I added the Seven People Records sub label just recently in 2024. It got a bit more serious over the last years as I am now shipping to stores and a few distributors, but it is still a hobby that mostly just covers costs. I used to sneak flyers on the copier at work, handing them out. Then I sent postcards. Then I called and texted. Then I sent emails. Now I make stories and reels. It just keeps changing, but the music is what keeps me current and makes me keep sharing it with the world in whatever way is available. The biggest lesson through all these changes is really to trust your inner voice. That could have helped me a lot back in the eighties and nineties.

You worked with a band to create Damn the Machine’s music, but your solo stuff is more of a singular vision. How do you switch gears between a creative process that is all about collaboration and one that is more personal and controlled. Do you find one more satisfying than the other, or do they serve different purposes for you as an artist?

I like both, but I am not a big fan anymore of spending endless hours in the practice room. I write and choose my favorite material at home when I am in a good mood, and then I bring it to the guys in the practice room to test it out. I am lucky to have great people around me and I always somehow have had great bandmates. I do a lot of the vision part myself, but my band helps me carve out the final versions. Switching gears is easy because this has become like a yearly event for me. Creating, collecting ideas, throwing them at musicians, and seeing what comes back. If nothing comes back, I try another musician, throw it in the trash, or try it acoustically. There is always a way forward.

You once said that you like to hide behind your songs and let them work their magic. When you are re releasing music from decades ago, is it easy to still feel that distance, or does it pull you right back into the emotions and memories from when you first wrote those songs?

As much as they are a part of me, it is such a long time ago that there is a degree of separation that protects both me and the music from any emotional danger. I feel even more today that I hide behind the songs than I did in the past. I really appreciate the creative process and some of the shows, but my main goals are in creating and releasing, setting the songs in stone, and leaving them there.

The title of your latest album, ‘Everything A War,’ is very powerful. When you look at your entire musical journey, from the early explosive days of Damn the Machine to your more recent personal songs, do you see your whole career as a kind of war, maybe against creative burnout or something more personal. What does winning that war look like to you?

That is funny and very accurate. Rolling Stone magazine wrote something very similar. I remember a line that said, “We do not know if Clemmons has won his war now with ‘Everything A War,’ but he definitely sounds satisfied.” I love that quote. In my opinion, this album is the closest I have come to my dream album, a collection of everything I have learned, and many of my best friends working together with me.

Okay, last one. We have some spare time and you can choose three albums we will listen to. What would you play?

Neil Young, ‘Rust Never Sleeps’

Jackson Browne, ‘Late For The Sky’

Bjork, ‘Homogenic’

Thanks for the great questions. I enjoyed answering them.

Klemen Breznikar

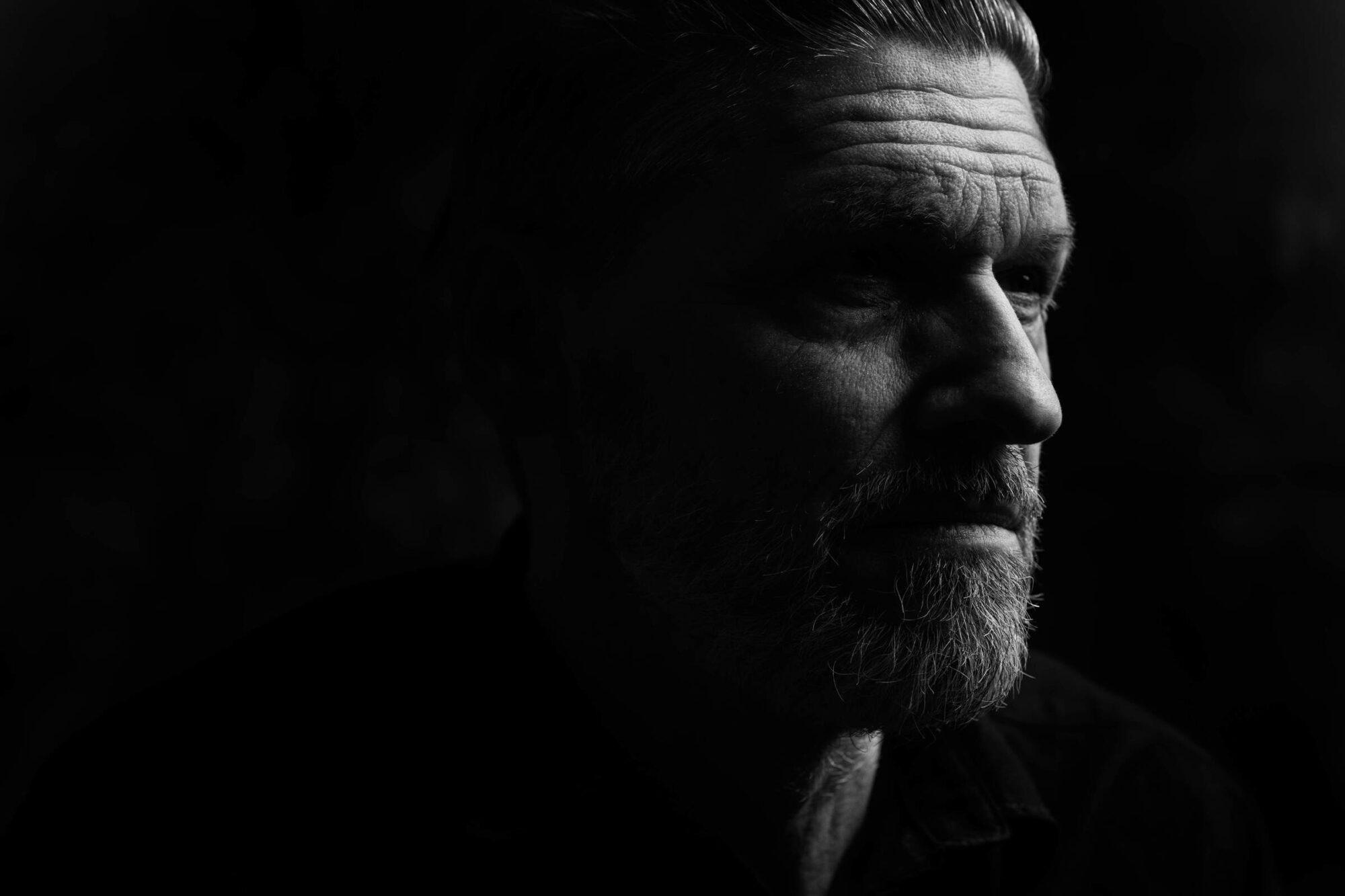

Headline photo: David Judson Clemmons (Photo credit: Caroline Wimmer)

David Judson Clemmons Website

Damn The Machine Website