The Final Solution: A Lost Voice of the ’60s San Francisco Sound Emerges

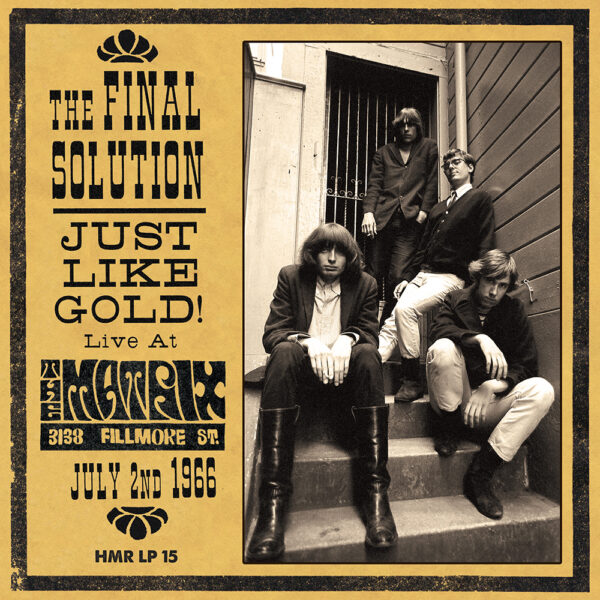

The legendary, yet little-recorded, San Francisco band The Final Solution has finally received a long-overdue official anthology of their extant recordings with the release of ‘Just Like Gold: Live At The Matrix 1966’ on High Moon Records.

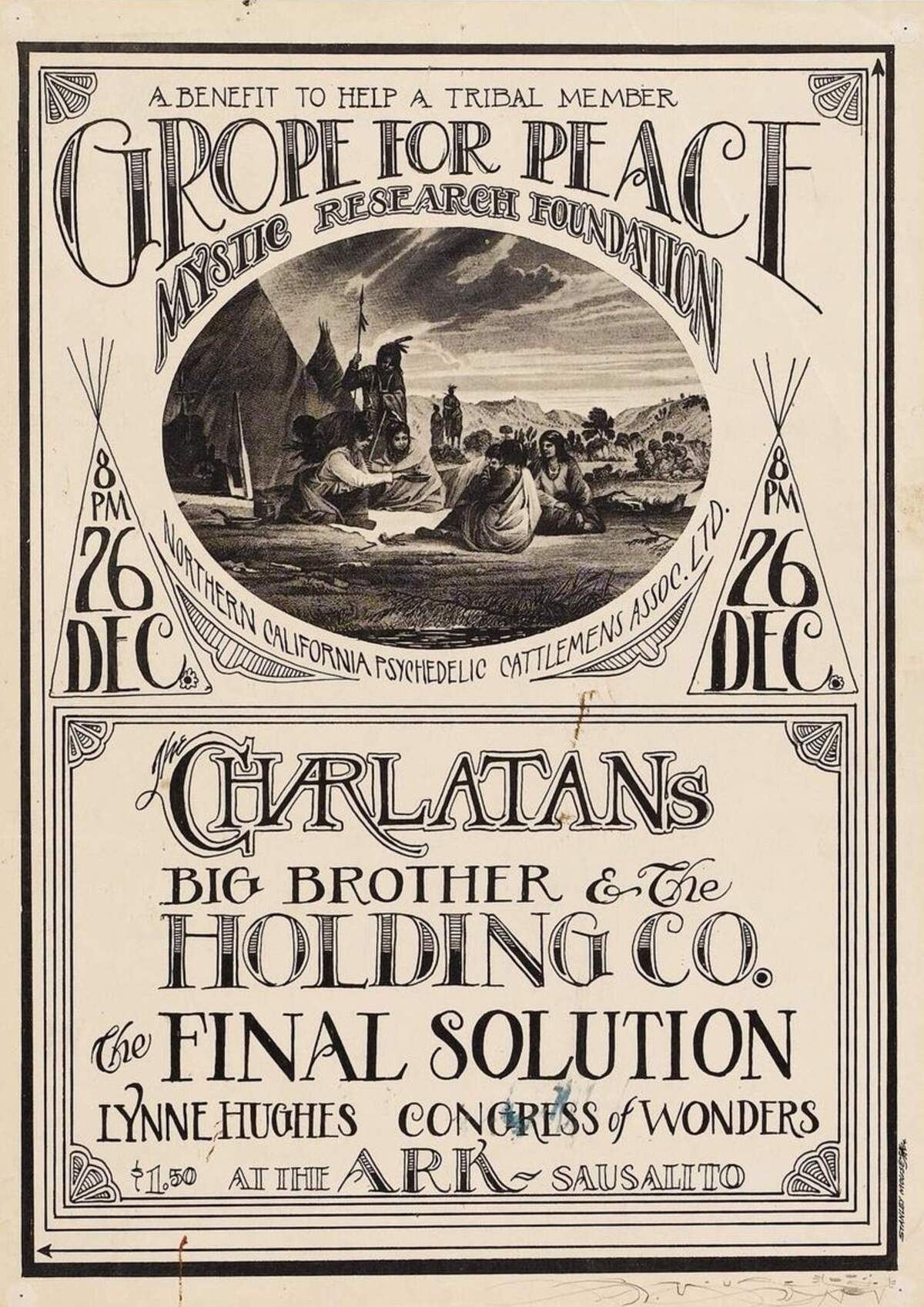

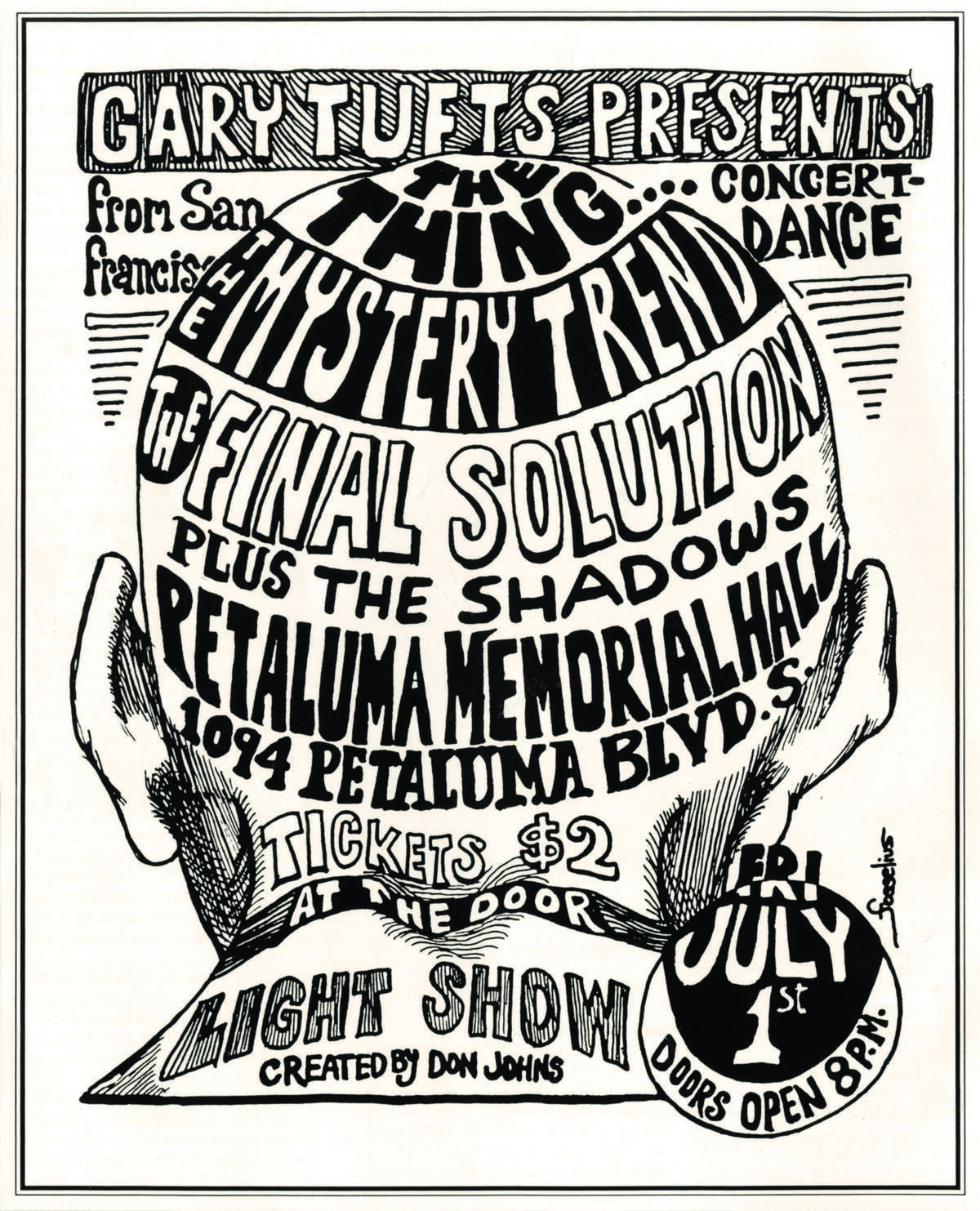

Though the group’s career was over before the Summer of Love even began, they were an intriguing part of the mid-1960s San Francisco rock scene, sharing a bill with prominent acts like Quicksilver Messenger Service at the Fillmore Auditorium.

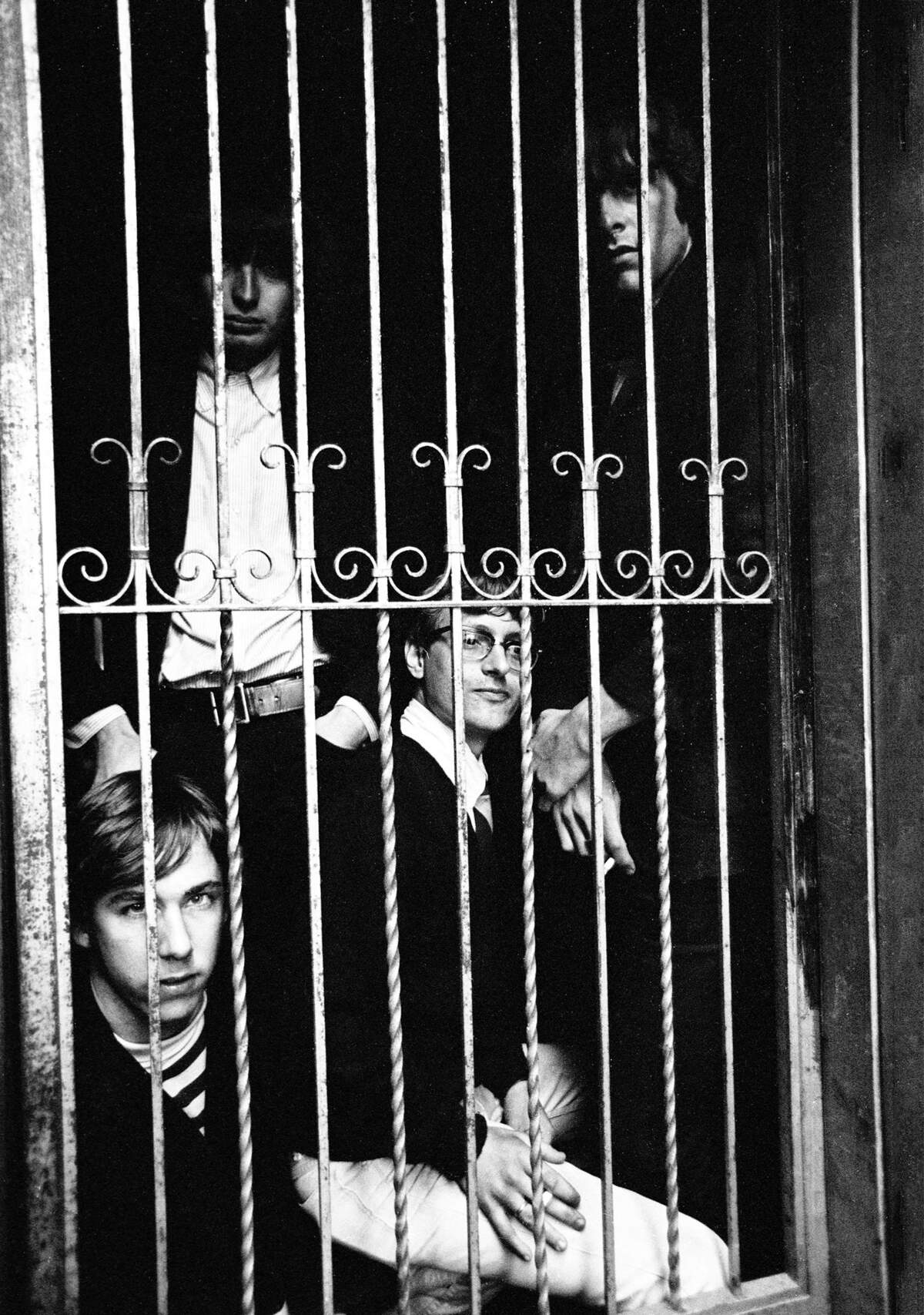

Comprising bassist Bob Knickerbocker, guitarist Ernie Fosselius, drummer John Chance, and guitarist/vocalist John Yager, the band was a product of the ferment at San Francisco State, a melting pot of personalities that fuelled the burgeoning bohemian scene. Their music was a cutting-edge folk-punk sound, brimming with the heady air of early psychedelia.

The core of the release is a blistering live set recorded in July 1966 at San Francisco’s famed Matrix club. Drummer John W. Chance recalls that the band filled in as a last-minute replacement for The Great Society. The performance, captured by Peter Abram’s tape deck, clearly demonstrated the band’s diversity and musical chops.

The album showcases original songs that prove the band’s untapped potential. Tracks include the “distinctive raga feel” of the opening ‘Tell Me Again’ and the Dylan-esque folk-rock of ‘Bleeding Roses’. John Chance notes the album’s emotional centerpiece, ‘The Time is Here and Now,’ felt like their “real anthem because it reflected everything we lived and felt in our daily lives.”

The original Matrix reels have been newly transferred by Alec Palao, who also undertook extensive audio preparation and restoration work, before being expertly given the final mastering touch by Dan Hersch. The result is a sound that is remarkably deep, sharp, and clear—at times akin to a studio recording. This authorized High Moon Records release also includes rehearsal tracks featuring later drummer Jerry Slick, and comes packaged with a lavish booklet containing a detailed essay by Palao himself, adding essential historical and musical context.

The band members’ philosophical stance, captured in the music, was one of generational solidarity and a critique of conformity, encapsulated by the motto they adopted: “There is No Final Solution”. For John Chance, hearing the remastered music now is “like hearing the music for the first time”. He hopes the band’s legacy will be to help listeners get a “little high, psychedelicized, and seeing yourself as the originator of your own life”.

“There is No Final Solution”

John, let’s start at the very beginning. You and the other members, Bob Knickerbocker, Ernie Fosselius, and John Yager, were all connected through San Francisco State. Can you take us back to that time in 1965? What was the atmosphere like, and what inspired you all to come together and form The Final Solution?

John W. Chance: OK. Let’s go back to 1965. Actually, let’s go back to June of 1964, when my best friend Tom King and I moved into the Haight Ashbury. At that time, the Haight was a run down neighborhood of unfashionable old Victorians. Golden Gate Park’s panhandle was just a block away. We had been looking for a cheap place to rent since we were both going to SF State in the fall, and then we found the seven room third floor flat at 1732 Page Street for $115 a month. Actually, that was outrageously high since a typical San Francisco rental then was about $40 a month. We figured we would split the rent by bringing in other people. Well, we weren’t the only ones with that idea who already had, or were students now doing the same thing all over the Haight. This area was, as we would find out, populated by artists, ex-beatniks, and just plain way out cats. For example, on the first floor, 1730 Page, lived Chris Newton, a guitar playing folk singer; the poet Allen Cohen, later founder of The Oracle and a major spokesman for the Haight; and one or both of the Thelin brothers, Jay and Ron, who started the first Psychedelic Shop. Frequent visitors there were Chet Helms and Danny Rifkin, who may have briefly lived there.

The Haight then was really off campus student housing. People you would see at State you would see there, and vice versa. Rodney Albin, Mike Daley, Dan Hicks, drummer for The Charlatans, Richie Olsen, who played bass in The Charlatans, actually I had known him back in 1962 when we were both music majors at State. I was living at 326 Castro then, Rock Scully, a graduate student, and Danny Rifkin, later both managers for The Grateful Dead, Jamie Leopold, later double bass player with Dan Hicks and His Hot Licks, as well as Bob, Ernie, and Jane, whom I would all later meet. Many other people I would recognize by face only, having seen them at State and on Haight or Page Street.

Now we were all affected in one way or another by the Beatles and Beatlemania. I am sure it was not just Grace Slick who got the idea from them of starting a rock and roll band. Bob had even bought the Paul McCartney Beatle bass, the Hofner 500 1 bass guitar. He was living with Ernie at the time, and I think they mutually agreed to start a group. Later, my roommate Gary Tufts said they needed a regular drummer to replace Doug, their conga player, so I auditioned. Sixteen year old John Yager, whom we always called The Kid, joined as rhythm guitar and vocalist. He had been taking guitar lessons from Jerry Hahn. Since John had skipped two grades, he had already graduated from high school. Then with us he turned seventeen.

The other big influence on campus had been Bob Dylan and a few other folk singers of the early 60s. His plea for integration, ‘Blowing in the Wind,’ 1963, his anti-war ‘A Hard Rain’s a Gonna Fall,’ 1963, his ‘Masters of War,’ 1963, which decried America’s hypocrisy, and especially his ‘The Times They Are A-Changin’,’ 1964, seemed to speak for us, expressing how we all were thinking and feeling. A new way of thinking and living was on the rise, and we were it. But by 1964, many folk singers, bluegrass and jug band members from the old coffeehouse days were switching to electric guitars: Jerry Garcia, Country Joe McDonald, David Crosby, Paul Kantner, Jorma Kaukonen, Ernie Fosselius, and on and on. Folkies with amplified guitars. Folk music gradually blended itself into folk rock. And of course, Bob Dylan made the switch to electric himself as well, but that was later in 1965. Still, it was more proof of our revolution, the changing of the times.

State College was a lively center for music. You would see musicians wandering around all the time, whether they were students or not, since so many people knew each other. Groups often played, I guess for free, in front of The Commons on the grass. I saw Buffalo Springfield and The Great Society there. New groups were forming in the Haight and at State. These were the places to be. One day, while sitting in the Commons, Luria came in passing out posters for the first Family Dog Longshoreman’s Dance Concert, A Tribute to Dr. Strange. Naturally, Dr. Strange had already been my favorite Marvel comic book character for quite some time. He split a comic with Nick Fury, Agent of SHIELD. We recognized each other at once. She was Loretta, then Loret, Castell, whom I had known since 1961.

Way back then, as a student at Petaluma High School, PHS, I had gone with the other members of my band The Shephards, including Dexter Parker, to see folk singers Kristina Parker and Caryl Esteves, both 1960 graduates from PHS, perform the first song I ever wrote, The Ballad of Charlie Starkwether, 1959, at a coffee house in San Francisco. Later, at their apartment, I met Loretta Castell, a political activist who had been to Cuba, illegal at the time, and had also recently been hosed down the steps of San Francisco’s City Hall when protesting the House Un-American Activities Committee, HUAC, hearings there. She gave me an Aldermaston button, soon to become the Peace button, which became the leading symbol for peace over the next twenty years. Another time, in 1962, when she had broken up with her husband Michael, we had gone to a mountain retreat I had access to in Corte Madera, where she would cry to weepy pop music.

But now she was way beyond all that and was deep into the psychedelic music scene, like so many of us. She had taken a major role in the new Family Dog with Chet Helms and now went by the name Luria. Later on, she is known for her famous quote, We need a place to dance. The times were certainly a changing. Frankly, during the peak years of 1964 to 1965, we were all living in a dream. A free spirited mecca for artists and musicians. An anarchic subculture. Anything that stretched the limits of understanding, including drugs. Free access to people’s flats for Friday night parties. Mocking conventions. A sense of generational solidarity different from other generations.

The band’s early days were spent playing Haight Ashbury dives, which eventually landed them a month-long residency at the Red Dog Saloon. What do you remember most about those gigs, and what was it like to be an up-and-coming band in such a vibrant and competitive scene?

Of course, as I have tried to make clear in the liner notes to our newly released album, ‘Just Like Gold,’ I learned in high school and knew full well the historical meaning of Hitler’s “final solution to the Jewish problem,” which was to gas to death the prisoners in Germany’s Auschwitz concentration camp with Zyklon B. I objected to our adopting the name. My mother winced and was shocked by our taking it as a name as well, and I had tried to get Bob and Ernie to change it to “The Present Tense” because of the song we played, ‘The Time Is Here and Now.’ They were totally against it, probably owing to Bob’s and Ernie’s eccentric, surrealistic, and offbeat senses of humor. That became obvious to me the more I got to know them. You can hear it in a couple of our songs’ lyrics that the name was not intended to refer to anything from World War II but had a new meaning: no solution is total.

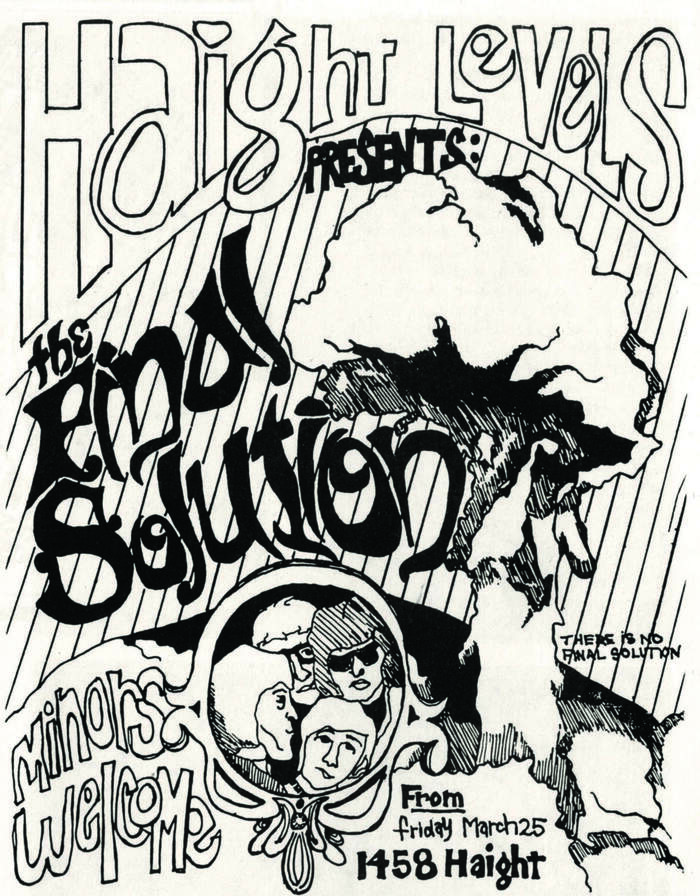

So at our Haight Levels gig, we adopted as our motto “There is No Final Solution,” which was suggested by Ernie’s sister, who designed the poster by the way. I wanted this to be the name of our album release, but I did not mention it to Alec Palao. Maybe for our next one. Bob and Ernie thought there was no final solution other than to live life as it is. Their philosophy was similar to that expressed so lyrically in Bob Dylan’s song ‘My Back Pages’ (1964): “Fearing not that I’d become my enemy in the moment that I preached,” and “Good and bad, I define these terms quite clear, no doubt somehow, ah but I was so much older than I am younger than that now.” In other words, anyone programming a final solution is wrong. You may have even heard Wolfgang Niedecken’s Kolsch cover version.

Two of Bob and Ernie’s songs seemed to carry their philosophy and the message that there was no final solution. In ‘You Lost Your Ego,’ described in the “psychedelic” section below, there is a cut version on the original Pine Street rehearsal tape where Jerry Slick played the drums. Its repeated line “it just is” referred to the idea that any philosophy that sets rules or advocates methods of change is not really needed because life just is. Do not preach it—just be an example and live it. There is no need to push philosophies on people. Just live the life you mean, whether you are peace marchers or self-proclaimed drug or free love addicts. In ‘Tell Me Again,’ the lyrics say, “Tell me again that you have the answer now and I’ll tell you again there is no question anyhow.” Bob had a habit of writing on objects with flow pens—for example, on a table he would write “this is not a table,” and on a 7-Up can, “this is not a can.”

The band’s name did not really set us apart from anyone in the Haight, since our musical sensibilities, including minor keys, strong guitar solos, vocalized disenchantments, introspections, and irreverence, spoke for themselves. As is well documented in various books and histories of San Francisco from 1964 to 1969 (see the list of my “Memory Joggers” at the end of the interview), when baby boomers left high school and entered the world, many who were seeking to freely express themselves suddenly noticed that they had moved to a progressive artists’ colony of free-thinking young people, musicians, beatniks, freaks, and college students—the Haight Ashbury. As a musical part of this new rock and roll centered youth rebellion, with its disenchantment of straight traditional values and American hypocrisies, we were just adding another voice to this rising tide of creative free living.

There were literally a hundred local musical groups up and down the Bay Area Peninsula, and strange names were not uncommon: “The Vejtables,” “Quicksilver Messenger Service,” “The Mojo Men,” “The Tikis,” “Count Five,” “Country Joe and the Fish,” “Moby Grape,” and the wonderful “Grateful Dead,” which by the way was not the Department of Defense’s official military band for America’s annual Veterans Day Parade. I do not think people in the Haight paid much attention to the names, since it was really all about the music itself anyway. The anthem there had long been Martha and the Vandellas’ “Dancing in the Streets,” released in July 1964. I doubt that the suit-and-tied business majors at San Francisco State were flocking to be fans of “Big Brother and the Holding Company” because of its name. If they did, they would probably switch to hippie clothing.

Well, we auditioned at the Red Dog at the end of June. In mid-July we signed a six month contract with Mainstream Records. They wanted us to record in Los Angeles in August. They gave us a list of numbers to perform there: ‘The Time is Here and Now,’ ‘If You Want,’ two slow songs by Ernie, ‘Walking Alone’ and ‘Live Love,’ and two fast numbers by the Kid, both of which we frequently opened with, ‘All Good Things’ and ‘My Room’s on Fire.’ They would pick two to record.

The first week of August we began a month long gig at The Red Dog Saloon in Virginia City, Nevada, where The Charlatans had started. I was not looking at the big picture the way Bob and Ernie were, as they were the driving forces behind the group. I was actually two people: one was a student, since I was still heavily involved in my college work. I was just going with the flow. Fame would come when it came.

I loved playing at The Red Dog. The décor inside the place was fantastic, with all red velvety walls and period lighting, except for Bill Ham’s light machine on the stage. We played Thursday through Sunday nights, with room and board provided. We even practiced there during the day. We tried out different songs, including Ernie’s “Baroquen Window” guitar solo and my song ‘Tired,’ a couple of times. That was the second song I had written about a dream-fantasy girl I knew at San Francisco State, the first being “If You Want.”

We were off three days a week, so we often hung out at different bars and restaurants and even took side trips to Carson City and San Francisco, the City. Jane Dornacker came up one week, and we went over to The Bucket of Blood, where she would sing and play piano. One time I took my violin because I wanted to sit in with their country music band. While sitting at the bar and needing a light for my cigarette, I asked the big booted cowboy next to me, “Have you got a match?” He barked, “Yeah. Your face and my ass!” He then pulled my hair down and pounded my head on the bar twice.

A little later, he asked, “Can you play the violin?” I got up on the stage, fiddled in the background with the country band, and then went up to the microphone to accompany them on ‘Under the Double Eagle’ (1908), an old German march that was a country music staple. I mostly faked it with a lot of heavy foot stomping. When I got back to the bar, the same cowboy bought me two beers and made me drink them both at once. Ah, music conquers all.

Virginia City was going to hold its annual camel and ostrich races. I was staying in a house where the food was being stored by the camel wrangler. I do not ever recall being paid by the Red Dog. One night, in order to eat, I took some of the cabbages and carrots and made a soup for myself and my girlfriend, who had come up that week with some other friends from Santa Rosa and the City. One of them, Don Lingle, was eager to ride a camel. He did, but the ostriches were so recalcitrant that they never raced. Ernie made a fifteen minute musical exploration of this and our other adventures on his ‘Virginia City Summer Symphony’ (1966). If I ever played it for you, that might make Ernie try to contact me after all these years.

The core of this new release is the live recording from July 1966 at The Matrix. Can you describe that night? What was the energy like, and did you have any idea that Peter Abram was running a tape recorder?

First of all, it was a setup. Bob and Ernie knew Jerry Slick, as they were all in the Radio TV Film [RTF] Department at State. Bob made a deal. The Great Society was actually appearing at the Matrix that week, but they agreed to call in sick so we could replace them. Well before show time, we were all sitting in a parked car off Divisadero Street, smoking a joint and listening on the car radio to the very entertaining, humorous, and musical DJ Sly Stone, who was on the Oakland black radio station KDIA. It turns out he was also working as a record producer for Autumn Records. Ernie, however, never smoked pot or took any drugs.

Then we carried all our equipment in, set everything up, and played two sets, between which we smoked another joint in the back room. You can hear the pleased reception we got on the LP and CD. These are live moments captured of Haight Ashbury’s sensibilities.

We took the whole thing in laid back stride. Bob and Ernie maintained their usual reserved coolness, while the Kid and I were anxious to play before our first club live audience. Bob always wrote out the sequence of songs, and ‘The Time is Here and Now’ was usually first. I did not know Peter was always recording the performances, as he had done for The Great Society. Peter also produced the album releases of their sets at the Matrix: ‘Conspicuous Only in Its Absence’ and ‘How It Was,’ in 1968.

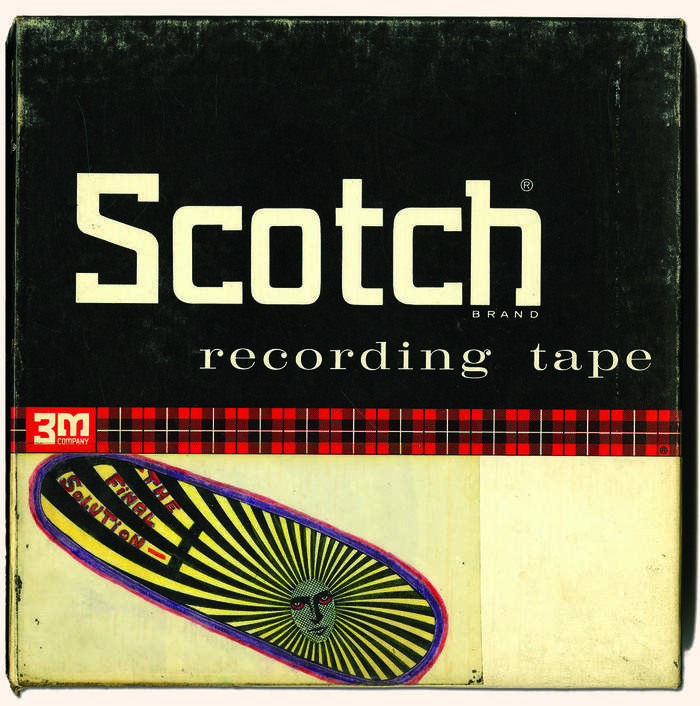

As we were leaving, Peter gave a reel-to-reel seven inch per second tape copy to Bob, who did not want to hear it, so he gave it to me. Of course, all these years later, I gave it to Alec Palao, and here we are.

The album opens with ‘Tell Me Again,’ which has a distinctive raga feel, and ‘Bleeding Roses’ is described as Dylan-esque. What were the specific influences behind these two songs?

I do not know if Bob, Ernie, or I were consciously adapting anything from The Great Society. They knew Jerry Slick, who was also in the RTF Department at SF State, and they had seen The Great Society perform. The Society even performed once outside the SF State Cafeteria on the Commons. Now, if you listen to their version of ‘Sally Go Round the Roses’ (1966; album release 1968), with Grace Slick on the organ, it is definitely raga scale music. This was not unfamiliar to us in the audience, since all of us cool cats in the Haight had long been dabbling with Eastern philosophies, listening to records of Northern Indian Ravi Shankar’s raga music or to Sandy Bull’s ‘Inventions’ album (1965). So many millions of young people throughout the world, of course, had been introduced to Indian music because it was featured in the Beatles’ second film, ‘Help!’ (1965).

From the time I moved to the Haight in June 1964, I was introduced to and encountered a world of people, whom we called groovy cats or really hip cats, who were into all kinds of different philosophies. These ranged from the works of the Beats, mostly Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg, to Hinduism, Bahai, Buddhism and Zen, including Alan Watts, the book of the I Ching (mentioned in Country Joe and the Fish’s ‘Not So Sweet Martha Lorraine,’ 1967), G.I. Gurdjieff, Aleister Crowley, Carlos Castaneda, and even the esoteric Madame Blavatsky and The Urantia Book, which I still have a copy of. There was even a Mystic Book Store with all these works displayed way up on upper Polk Street, across from the groovy bars, restaurants, and clothing stores everyone went to. One such bar there is featured in Ernie’s famous Hardware Wars film.

Everybody was aware of or into raga type music, as we were when we were already including ‘Tell Me Again’ in our sets in March. Then came the movie Help! (1965) and George Harrison being the first Western musician to actually play sitar on a record with ‘Norwegian Wood: This Bird Has Flown’ in December 1965. Then Brian Jones played sitar on ‘Paint It Black’ by the Stones in May 1966, which the media proclaimed as the start of raga rock, a style that had long been part of the Haight Ashbury musical scene. Donovan followed suit, of course, including Indian instruments playing a fantastic break on ‘Three Kingfishers’ from the ‘Sunshine Superman’ album in August 1966.

Everyone was into raga type changes, keyboard explorations, and key of D guitar tunings. We had been playing ‘Tell Me Again’ since at least early March. Since Jerry Slick was a good friend of Bob and Ernie, I am betting that it was the way The Great Society transformed ‘Sally Go Round the Roses,’ which had a limited release as a single in 1966, and also ‘White Rabbit,’ which featured a long raga-like solo by Peter Vangelder on the saxophone, that had the biggest influence on them. Peter, by the way, was studying sarod and sitar at the Ali Akbar College of Indian Music in Marin County, along with Darby Slick, their guitarist and Jerry’s brother.

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band was the first non-San Francisco group to play at the Fillmore Auditorium on May 25 to 27, 1966, in a concert put on by The Family Dog. Mike Bloomfield on guitar had backed Bob Dylan when he went electric at the Newport Folk Festival. Maybe Bob and Ernie were at this concert, I do not know. The band played their thirteen-minute ‘East-West’ piece, written on LSD after listening to Ravi Shankar one night. The song did not appear on any LP until the band’s second album in August 1966, East West. ‘Section 43’ by Country Joe and the Fish, a semi-raga inspired instrumental, did not come out until their second EP in June 1966. But I do not think we paid much attention to it; ‘Tell Me Again’ sounded better.

As mentioned above, Bob wrote the words to ‘Tell Me Again’ as a partial expression of his philosophy. Usually Bob would write the words to the songs and Ernie would create a melody. There was no melody for this one, so Ernie just said to the Kid, “Make up a song,” and he did.

Ernie told me one time that he did not understand the words to ‘Bleeding Roses’ and that they did not make any sense. Bob had written the words in imitation of the ambiguities and seemingly odd juxtapositions in some of Bob Dylan’s lyrics, such as ‘Tombstone Blues’ (1965) and ‘Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again’ (1966). A lot of popular songs of the time also had equally off the wall lyrics. Whenever we played ‘Bleeding Roses,’ I could not help but see images of the Vietnam War: the fields of bleeding roses were too thick to walk through, and the fields of those roses were too much for you. In other words, the “bleeding roses” were the dying Vietnamese—women, children, and soldiers. That is the thing about ambiguity in poetry; it can be about whatever you think it is.

I do not think I was copying anything from The Great Society’s song ‘Someone to Love’ when I wrote ‘If You Want,’ although I had a reel-to-reel tape of the Society that I probably got from Bob. The chorus of the song was the typically common repeated chorus structure from many past hit ABA songs of the late fifties and early sixties. That is why “Someone to Love” sounded so pop, unlike most of their other songs. So “if you want to say that” just automatically popped into my head, followed by one of the Kid’s typical negativities: “it’s no good for you.” Actually, I had used it before in several other songs I had already written. I told the Kid I wanted a sitar for the break in the middle of it, but Ernie did not have access to one, so he did his best wobbling around on his guitar.

‘Just Like Gold’ is the title track and a standout. What is the story behind that song? What was the band’s songwriting process like?

The Kid wrote it; he was seventeen at the time. I thought he was influenced by ‘Paint It Black’ (1966) by The Rolling Stones, but who knows what was going on in his mind? I never could figure out exactly what it was about, but the minor sounding “downness” was good enough for me, especially with Ernie’s fuzz guitar. When the Kid introduced it at practice, Bob, Ernie, and I just made up our parts. Bob liked to play in a low minor key style. Usually, my approach was to follow and accompany whatever was being played, like in my days playing written parts for drums, tympani, xylophone, and other percussion instruments in junior and senior high school bands in Petaluma.

As for his lifestyle, I knew very little. He usually made decisions by throwing the I Ching, though I do not think he did that during practice. We just hung out to play music together. The Kid was a very fertile songwriter and always seemed to be writing new material. Throughout my association with him and his music, he could write tender songs about love, such as ‘Inside Your Life,’ ‘Ramona,’ and ‘September Morning,’ as well as songs with lots of off-the-wall ambiguities about the negative aspects of life and society, such as ‘The Streets of Sodom,’ ‘The Valley of Fire,’ ‘Capital Killing,’ and the just plain obscure ‘The Roman Marshall Variation’ and ‘The Tide of the Old Ocean’s Lies,’ all from 1968.

He would play a new song for us, and Bob and Ernie would decide whether to take it or not. They always did. When the band first started playing together, we would open with one of his 1966 songs, ‘All Good Things (Must End Someday)’ or ‘My Room’s On Fire,’ the latter based on the true story of all our equipment burning up in a fire.

He and I spent a lot of time together, even though I was the oldest member of the group and he was the youngest. We would either be playing guitar at his or my apartment, where we wrote ‘If You Want’ together and initially worked up ‘Truck Driving Son a Gun’ (1965), a song I wanted to sing. Then we would present what we had done to Bob and Ernie at practice, and they would fill out the parts.

Usually when we practiced, Bob or Ernie, singly or together (Ernie writing the music), had already written songs that the Kid and I would learn. We did some of Ernie’s songs when we auditioned for Mainstream Records, including ‘Walking Alone’ and ‘Live Love,’ both from 1965. The only times we ever jammed to make up a song, besides ‘The Star Spangled Banner,’ were when we took the chords from ‘Born in Chicago’ by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band (1965) and jammed on it, with the Kid making up new words. We called it “BEFD Mojo,” but it is called ‘You Say That You Love Me’/’Got My Mojo Working’ on our album.

‘Bo Diddley Meets Sandy Nelson’ on the original Matrix tape was also an instant jam we made up, probably started by me. These two covers were an opportunity for Ernie to play the harmonica, of which he had several in different key signatures. He kept them in a jar of water.

For a band that was so active, very little was recorded in a studio setting. Why do you think that was the case, and do you feel the live recordings truly capture the essence of The Final Solution’s sound?

We did not really have a good, strong manager like Chet Helms or Danny Rifkin. I was never involved in any negotiations, since I was usually attending classes at SF State during the daytime. We did an audition for Mainstream Records, and they signed both us and Big Brother and the Holding Company. We also did another audition for Golden Gate Records. The one the group did without me was at SF State, where they named it as being by “Chuckles the Chipmunks and the Swine.”

Probably because Bob, Ernie, and Jerry were all in the Radio TV Film Department, we made a tape in its recording studio. With Mike Wright manning the controls, we did seven instrumental takes of ‘If You Want.’ We never did get to the vocal tracks. The best version was Take 7, with Ernie’s solo sounding a little Jefferson Airplane like. I put the take on various cassette tapes. A year or so later, Ernie and I tried to turn it into a radio commercial. (See our commercial, “Universal Trousers,” below.)

We got tighter the more we played, occasionally performing at the San Francisco Art Institute’s outdoor lawn area. To me, the group really became great sounding with Jerry Slick. On our CD, you can hear real differences between the four Matrix songs and their Pine Street rehearsal versions. I will explain them in a little bit. But I have to say, after hearing the fantastic new remastering done on our album by Alec Palao and Dan Hersh, the music sounds like it was recorded in a studio.

The Matrix recording features a unique arrangement of “America the Beautiful.” What was the thought process behind taking on such a well known patriotic song and giving it your own spin?

At one practice, we were trying to come up with a sign off song to end each set. The Grateful Dead initially used “Teddy Bear’s Picnic” and Quicksilver Messenger Service may have even used ‘Happy Trails.’ Ernie and Bob, with their ever present wit and offbeat humor, began playing ‘The Star Spangled Banner.’ The Kid joined in, playing screwed up, off kilter, distorted chords that reflected how we all felt about America’s twisted adventure in Vietnam. These were the years when the elephant in the room was the Vietnam War. Although none of us were peace marchers, it was automatic among all of us in the Haight that America’s Cold War trance was antithetical to the world we were creating and living in. It was something we ignored, lived outside of, and in our own way counteracted by offering a better alternative lifestyle, the world of peace and love, “Make Love, Not War,” and “War Is Not Healthy for Children and Other Living Beings.”

It later turned out that in December 1965, The Committee, San Francisco’s improvisation comedy troupe, wanted a rock version of the national anthem to open their second hour. One of their members, Howard Hesseman, who years later became an actor on the television comedy show WKRP in Cincinnati, asked Quicksilver Messenger Service to do it. They made the tape, complete with cowbell, for a dime bag of pot. I do not know if they ever played it on stage.

When we opened for them at the Fillmore in May 1966, I do not think they did it, but we did, to close our set. As soon as we started, the whole audience formed a huge conga line, bunny hopping all around the giant ballroom in a large circle. That was our statement against the war.

Even after all these years, my favorite version of ‘The Star Spangled Banner,’ other than the one my daughter Kristina sang to open a San Francisco Giants baseball game against the Cincinnati Reds, which she sang like it was a love song, is the one Jimi Hendrix played at the Woodstock Festival in 1969. He made it sound like the bombs were really bursting in air, over Vietnam.

Life in the Haight Ashbury neighborhood at the time was famously a mix of creativity and anarchy. Can you share a funny or crazy story from your time playing gigs or just hanging out?

Since I was so busy with classes at State, I never hung out with Bob and Ernie very much except during practice and gigs. In those early days of summer 1966, the Haight itself was becoming more and more crowded with free spirited and bohemian types from all over the country, including teenagers, runaways, and even pre teens. On Haight Street, there was really nothing to do except hang out with whoever was there.

Sometimes, for fun, if we were driving down Haight in Don John’s car, Bob would yell out the window to the street people, “Get a haircut. Get a job.” These were the same things we had been yelled at countless times by “squares” driving past us on those same streets back in 1964 and 1965. Bob, of course, had longer hair than anyone on the street. This was his joke on the invaders. I guess that is about as crazy as we got.

You may have seen short films of us on YouTube. There we are walking or running along Ocean Beach or in the Children’s Playground of Golden Gate Park. I am not in them. Since I was spending my days at State College, that is Don Johns in dark glasses as my stand in.

The ultimate crazy time was in 1968, when my later band, Revolution, played at a Sexual Freedom League party on Parnassus Street in someone’s large basement, with mattresses all over the floor. This was decades before the free internet porn we all know today. The band was the Kid and me, my girlfriend’s brother Bob on bass, and a guy named Sid on guitar, with his wife singing. The SFL advocated for free love and was the brainchild of Jefferson Poland, a radical rabble rouser who hung out at State College. Bob had taken us to one of their meetings, and soon we were recruited to play for one of their big parties. Everyone was encouraged to be naked, but only our bass player took off all his clothes. The Kid thought it was ironic when he sang “The Streets of Sodom” to the vertically engaged audience.

Once, I was at a party at Allen Ginsberg’s house near the Department of Motor Vehicles at the end of the Panhandle. The Byrds’ first album was playing on a turntable. Because of Allen’s fame, the house was jam packed, with just enough room to squeeze past people, as he did, fully naked, right past me. Being partly or even fully naked was not unheard of at gatherings in the park, whether concerts or not.

Although I never hung out much at Hippie Hill, since I studied best at home, or went to the Human Be In in Golden Gate Park, I had taken acid that day and eventually wound up at the Fillmore to watch The Doors. That was when Jim Morrison talked about what had happened earlier, including the arrival of someone by parachute. I remember now that I had actually been there for that part.

One of my most treasured memories was actually from around 1973. I saw a poster advertising Mike Bloomfield and Nick Gravenites playing at what I believe was a drugstore in Lower Pacific Heights. I walked over there with my newest girlfriend, and in the far back corner of the store there they were, sitting on the floor. Mike played and sang, and Nick just sang. They had been performing together like this since the early 1960s, years before Paul Butterfield or The Electric Flag. We sat right in front of them as they played a full set. They were so professional that if I closed my eyes, it sounded like I was listening to four musicians. It was a key psychedelic experience, like the time I was walking along Ocean Beach and saw a giant swordfish leap up and arch across the water. Did I really see that? Yes, I did.

Did you get any airplay back then?

No, but local media were beginning to take notice of the San Francisco Music Explosion. Many groups were sought after to make radio jingles for popular commercial products. One that The Charlatans made was based on their classic ‘Alabama Bound’ (1966). It was a ‘Groom ‘N’ Clean’ hair grooming ad, which you can find on their compilation album ‘The Amazing Charlatans,’ finally released in 1996.

Somehow, Ernie was contacted by the ad agency that produced radio commercials for Levi’s Jeans. They may have had one aired by a San Francisco group, but I do not remember which one. He and I prepared a demo tape to play in their Marina offices. Part of it featured new words, about Levi’s jeans of course, set to the excellent instrumental ‘Take 7’ of ‘If You Want,’ which we had recorded at SF State. It was now called “Universal Trousers,” because Ernie thought trousers was a funny name for pants. I have attached the words below, so you can sing along while listening to the Matrix version of “If You Want.” Unfortunately, we were not signed by the ad agency.

“Universal Trousers” (Fosselius, Yager, Chance)

Sing it to the track of “If You Want: Take 7” or the Matrix version (Yager, Chance)

Verse #1: Everybody in San Francisco,

No matter what he does,

No matter how he thinks

Or how he cuts his hair,

He has at least one pair.

Chorus: A pair of Levis,

I’ve got a pair of Levis.

You’ve got a pair of Levis,

The Universal Trousers

Universal…

[Verse #2 is lost; Everybody in San Francisco,

So just repeat No matter what she does,

Verse #1 No matter how she thinks

With she /her] Or how she cuts her hair,

You know she’s got at least one pair!

Chorus: A pair of Levis,

I’ve got a pair of Levis.

You’ve got a pair of Levis,

The Universal Trousers

Universal Trousers…….. Levis!

What about psychedelics? Did you experiment with any, and do you feel any of that influenced the music?

Okay, now let’s get psychedelic. As I have already mentioned, moving to the Haight meant we were all free to live life the way we wanted, without convention or restrictions. It was a time to develop our own interests and deepen personal experiences, with introductions to trying new things, including drugs.

Over that first year, the first was Romilar, a potent narcotic cough medicine, which I tried a couple of times whether I was sick or not, from the SF State Pharmacy. Then I tried marijuana, LSD, DMT, Hawaiian Wood Rose seeds, peyote, and “magic mushrooms,” which a friend of mine’s friend brought back from Mexico. It was at 1730 Page Street that I first learned how to smoke pot. In Chris’s room, he played The Rolling Stones’ first album from 1964. I was thinking what a grungy looking bunch of bums, not clean like The Beatles. I had never wanted to listen to them. But on pot, as I called it, time seemed to slow way down. Each note of ‘I’m a King Bee’ seemed to last a long, long time, and I felt like a part of it. The three minutes of the song seemed like ten. I could not believe my ears and what had happened.

In November, at Chris’s place, I experienced the same intense involvement with The Kinks’ amazing ‘Got Love If You Want It’ from 1964, among others.

For my second time on pot, I experimented by listening to my own musical preferences, like The Beach Boys, to see what would happen. Listening to familiar music while “stoned” felt like being allowed to pass through hidden doors, opening up new feelings, experiences, and insights into the songs and performances. The arrangements and deliveries on their first three albums, ‘Surfin’ Safari’ (1962), ‘Surfer USA,’ and ‘Surfer Girl’ (both 1963), became revelations to me. Their integrated blending was so fluid and complete, each member of the group was like fingers on a hand, an image I usually tried in vain to explain to others.

I even tried singing my own songs while on pot and attempted to write new ones, a few of which found their way into ‘Chickaluma: America’s Greatest Musical,’ a project Tom and I had been co-writing since 1961 in Petaluma. At Kinko’s Printing, I finally had the revised edition printed in 2014. Music and marijuana went together; they played a major role in the life and sudden explosion of the Haight Ashbury music scene. It was always a thrill for me to listen to music while high.

So what about psychedelics? Some far out people lived around the corner in a large Victorian on Cole Street. I would visit my friend Fud, a groupie of our band; Lance Stevens, an abstract painter; a girl and her boyfriend who were meth users; and the intellectual Doug, whose last name I never knew. In the earliest days of LSD, it was common to have a guide to lead you through the experience, following the outlines set by Dr. Timothy Leary. Doug acted as the guide while I took the LSD. I lay down flat on a Tibetan type rug in his room after swallowing the sugar cube and waiting for its effects. He played recorded sitar or sarod music. Doug guided me by reading from Leary’s The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead (1964).

After the tingling and floating sensations on my back, one of the first major effects began: dechronicization, a sense of moving outside the conventional sense of time. Then dynamization started, where visually everything I saw began to move, bend, wiggle, and dance.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead is a guide for navigating the three bardos, the process of death, and rebirth into another form. Dr. Leary used the process as a metaphor for the experience of ego death, or depersonalization, a feeling of losing the sense of self and suddenly having an awareness of undifferentiated unity. The psychedelic internal journey was a metaphorical death-rebirth experience.

I was listening to Doug reading in his low, calm, soothing voice from the works of Ramana Maharshi, a Hindu sage from India regarded as a jivanmukta, or liberated being. Maharshi recited aphorisms that canceled out old ways of thinking and described the liberation of self. I felt cleansed. Roger Corman, who took LSD with his cast and crew while preparing for the movie The Trip (1967), called the experience “wonderful.” As Nick Gravenites sings in ‘Psyche Soap’ from the movie, “Psyche soap is the only soap that makes you clean inside.”

LSD is such a strong, personal journey. I am not sure how many times I took it, but it must have been somewhere around ten to twenty five times between 1967 and my last three times in the 1980s.

What were its effects on our music? Mostly indirect, and maybe a little direct. Ernie never took any drugs. The Kid, however, besides smoking pot, got hung up on methamphetamine for a while, and he was high on meth at the Ark performance. Bob probably took LSD, as most of us did. “Psychedelic” meant enhanced awareness of the moment, so you can guess its influence on the awareness of life’s immediacy in ‘The Time is Here and Now,’ ‘Tell Me Again,’ and ‘Nothing to Fear.’ Both Ernie and Bob were very singular, iconoclastic individuals. Many of their songs railed against ideologues, those who tried to impose their trips on others because they had found the true path, as in ‘Tell Me Again.’

One of our early songs, ‘You Lost Your Ego,’ part of which is on the ‘Pine Street’ tape, goes, “You lost your ego and you told me all about it / I can tell you’re humble by the way you shout it.” One of the worst cases was a local self-important guy who told me that he had given LSD to his three year old daughter, later known in life as Courtney Love. And who knows who was being referenced in ‘Misty Mind,’ ‘Just Like Gold,’ or ‘Bleeding Roses.’ Was it describing a bad trip?

In 1968 I wrote a song about LSD, ‘Here We Are Today (The LSD Song).’ Part of it goes: “Just let it go now / down to the ground / here we are today / Realize the power of the part you were given to play / realize the fullness of the heart that was given to you / because here we are today.” We were already “pretty far out” in our ways of life and thinking. Psychedelics did not really change who we were, but they were glorifying and liberating. Psychedelic meant consciousness expansion, which was key to how we wanted to live and relate to others, to blow their minds. As a forty year teacher of English as a Second Language, my goal was to expand non-native speakers’ minds by giving them greater control over the rational, critical thinking world of English. Question authority. As Bob Weir wrote, “We weren’t all stoned all the time. But we were all artists, musicians, and freaks all the time.” Once a freak, always a freak.

I could go on, so I will continue just a little more. While teaching at Treasure Island Job Corps, one of the math teachers, JT, was from Tibet. At that time I was doing my own research into the Tibetan Book of the Dead, listening to a cassette lecture tape I had, and watching the two-part documentary The Tibetan Book of the Dead: A Journey (1994) narrated by Leonard Cohen. This was because my older brother, who was living in Las Vegas, was failing health-wise. Recovery did not look possible, and death seemed near. He was in hospice care.

When all the academic instructors had a big dinner at a Spanish tapas restaurant, I told JT how, for all those years, I had thought the book was about taking LSD. We had a long discussion about its true nature over many beers. I learned a lot from the ever cheerful JT.

Later, in February 2013, my wife and I made our last trip to Las Vegas to prepare for his death and disposition. He had been moved to a hospice in Henderson, Nevada. He talked to our cousins on the phone and acknowledged my wife’s presence by squeezing her hand. I met with him privately, trying to soothe and comfort him, explaining everything I had learned from the book about accepting change, the process of dying, and letting go. I did my best to encourage him to let go and see the clear light. I do not know if anything I said helped him transition out of his body, but I felt I had been positive in helping him move on.

Here I am in the 2020s, living on Maui, Hawaii. My daughter is a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and sometimes uses ketamine in her therapy. In fact, psychedelics are back. In our current internet world, where information on everything is instantly accessible, why not go to psychedelicstoday.com? Oh, you already have?

After the Matrix recording, Jerry Slick of The Great Society played drums on a handful of rehearsal tracks. How did that collaboration come about, and what was it like playing with him?

When Grace Slick moved to The Jefferson Airplane as a vocalist, The Great Society disbanded. Jerry Slick was now available as a drummer. Since I felt I had to make a choice between school and the band, I decided to return to pursuing my major, American Studies, full time at San Francisco State. I was constantly reading books and writing essays and term papers for all of my classes, so it was time to focus on one or the other.

Jerry became my permanent replacement as the new drummer for The Final Solution. Since I was now out of the group, I never played with him or the band, except once, as noted below. I still liked to hang out and listen to them. I could not let go of the experience and the music. I was kind of like an appendix, serving no function but just hanging around.

That is how I got hold of the ‘Pine Street Rehearsal Tape.’ Pine Street was where the Kid was now living with his cousin and where the band rehearsed, which I wanted to hear. Ernie loaned me a five-inch reel-to-reel tape with some of their rehearsed music, and I kept it. This tape is where the six rehearsal versions on our ‘Just Like Gold’ CD came from. The whole tape had been bootlegged by Bill Combs, but not very well, back in the 1980s.

Here is the important part. Not only did Jerry bring his own drum set and distinctive drumming style to the band, he helped reshape and rearrange all of our songs so much that I thought of the group as “The New Final Solution.” You can compare on the CD how different the original versions are from the rehearsal versions under the new collaborations of Jerry and Ernie. Jerry also added parts of some Great Society songs into ours, which is described later on.

The rehearsal recordings with Jerry Slick, like ‘Nothing To Fear’ and ‘Blacklash,’ seem to have a different feel. What can you tell us about the lyrical and musical shift the band was exploring during that time?

The shift was primarily due to Jerry Slick becoming the new drummer. I am sure that by Jerry and Ernie essentially rearranging virtually all their numbers, the group’s interest in playing and their musical energy were both revitalized. Some sections of The Great Society’s songs were added to ours.

‘Nothing to Fear’ had been a collaboration by Bob and Ernie from their early days. Ernie gave it an unusual guitar rhythm, but I do not remember us ever performing it as part of our regular sets because it was too difficult. With Jerry Slick, however, it was revived using a drum pattern he had developed with The Great Society. In fact, several of the tracks on the Pine Street rehearsal tape feature him just playing the drum part so that Bob and the Kid could learn the rhythm. That middle part was in 8/4. It was actually the song ‘Arbitration’ by The Great Society that was added to Bob and Ernie’s original version of ‘Nothing to Fear.’ The cut you hear on the CD is just a shortened version of 4:01 without the long guitar solos Ernie played in live performance. When it was taped at the Ark in December 1966, it was 8:44 with long solos at the beginning and in the middle, and it was powerfully mind boggling for those attending. Unfortunately, the reel-to-reel tape was poorly recorded at 3 ¾ ips. Ernie did not like the shortened version eventually used for the CD because it omitted the major guitar solos. I felt it was disco-like in a weird way, definitely danceable and groove worthy. Alec must have agreed because he chose it for the CD.

Although not credited to him on our album, I think the Kid wrote ‘Blacklash.’ It sounds like his style, with lines like “train rolling and I don’t know where,” and he was always writing new songs anyway, even though Bob and Ernie were not. The “slow down then gradually speed up” part, so well played by Ernie in live performances, was actually the Society’s song ‘Father’ inserted in the middle of this two-part song.

Now I have to tell you about how they changed ‘Bleeding Roses.’ They made it more classical by modifying parts of it, reducing the number of verses and solos, and giving Ernie just one solo. The song went from 3:45 to 2:54. I was so impressed with it that in 1971 I made a note-for-note transcription for the group I was with at the time, The New Age Orchestra. I wrote out sheet music parts for two violins, trumpet with Chordovox, tenor saxophone, trombone, bass, and rhythm guitars while I played the drums. I have two versions of it on a CD.

When I joined this new group, I asked their original guitarist, who wrote their charts for songs like ‘A Summer Place’ and ‘Love is Blue,’ how he did it. He told me that you just put down the notes you want them to play. So that is what I did. I got a page showing the ranges and key signatures of orchestral instruments, and off I went. I taught myself. I would go to a piano practice room at State College, even though I was not a student there, and copied the notes from the tape. The group was the house band for a large commune I lived with for four years, but that is another story. I eventually wrote my own charts for ‘Dahil Sa Iyo,’ ‘Silent Night,’ ‘Mission Impossible,’ ‘Mexican Polka,’ ‘Life Goes On’ from the movie “Zorba the Greek,” and even a song by John Yager, among others. I also copied from printed sheet music for ‘Long and Winding Road,’ ‘Here Comes the Sun,’ ’25 or 6 To 4,’ and more. Well, that was then, was it not?

The song ‘Misty Mind’ appears in both live and rehearsal versions. What made that song so important to the band? What was the story or meaning behind it that you felt compelled to revisit it?

You are going to need a séance to call up Bob’s ghost to get the answer on that one. The words certainly fit Bob and Ernie’s view, as shown in other songs, that “life just is” and their rejection of ideologues who were trying to push their trip on others. On the original, I tried to play contrasting times to Bob and Ernie, who wanted part of it in ¾ time. I said people cannot dance to that, and Bob replied that we played dance concerts. I treated the whole thing as if it were in 6/8, which made the ¾ parts sound like triplets. I loved playing this one, not only for the drumming but also for the chorus, which I felt were positive affirmations of the anarchic lifestyle we all lived and were a part of. I would always sing along on the chorus.

When the new formation of the group was playing at a bar regularly, they wanted me to do ‘Misty Mind’ with them to show how the drum part went. I was not the only one who dropped by to see them play. In fact, I was sitting between Grace Slick and Michael McClure, the beat poet. I played it with the band, and I guess everyone was suitably unimpressed. If you compare versions, you can hear that they did switch the middle part to a definite ¾. When the Kid complained to Ernie that he never got a solo, Ernie told him to do the ¾ part in ‘Misty Mind,’ and he did. His early guitar lessons with Jerry Hahn, guitarist for The John Handy Quintet, certainly paid off, in addition to John Yager’s extreme talent.

I saw them again play a complete and powerful set indoors in the atrium of the New Fox Plaza opening on Market Street in December. I think the last time I heard them play was at The Ark in Sausalito. The Ark was a converted paddle wheel boat that doubled as a restaurant and dance ballroom called “The Gathering of the Tribes.” When they played there, gradually increasing the length and frenzy of the new versions of ‘If You Want,’ ‘Misty Mind,’ and ‘Nothing to Fear,’ the ballroom’s overloaded and frenzied crowd of wild dancers cheered and whooped with exhaustion and sweat. I watched the whole thing sitting next to Nick Reynolds of the Kingston Trio near the entrance. Another psychedelic moment for me, since when I was in my first rock and roll group, the Shepards, we used to sing Kingston Trio songs back in 1959. I have the cassette somewhere of their Ark performance, but as I mentioned, it was very poorly recorded. You can clearly hear everything I have described above.

‘Truck Driving Son Of A Gun’ is a fiery cover that stands out from the other tracks. What is the story behind that song being in your setlist, and what was the band’s approach to playing covers?

Of course, I could never sing as low as Dave Dudley, who did the original in 1965, but I thought the song was unhip enough for our group to play. I had heard it on a country radio station I listened to occasionally and had bought it from a used record bin, along with one by Sugar Pie De Santo, Hank Snow’s ‘Honeymoon on a Rocket Ship’ from 1963, and George Jones’ ‘If I Don’t Love You Grits Ain’t Groceries’ from 1963. I played the record for the Kid in my apartment on Waller Street, where we worked out the version, then took it to practice. Ernie and Bob, who worked out their own lick, were appropriately amused by it. Ernie was able to play his country style licks, as he does on ‘You Lost Your Ego’ and my own song ‘Mr. Fixit Man’ from 1965, which we later taped one time in his apartment on 17th Street, and which I usually did as my opening song when I performed by myself.

Now, as for covers, as I have mentioned above, I guess we did them to allow Ernie a chance to play one of his harmonicas. I am going to go out on a limb here, but I think Ernie may have been influenced by Paul Butterfield’s harmonica playing on his eponymous album from 1965, The Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Ernie definitely had a knack for it, as you can clearly hear on our LP and CD. What I called The New Final Solution, with Jerry Slick as the drummer, did one of The Great Society’s songs, ‘Grimly Forming’ from 1966, which is full of the usual verbal ambiguities. Their original version is on one of their albums.

In a scene full of bands like Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead, what do you think made The Final Solution different? What was your perspective on the hippie scene as a whole, and did you feel like you were part of it, or outside of it?

It was our attitude and musical style that made us different. Bob and Ernie were both deep sources of creativity and very individualistic, following their own jaundiced eyed muse. It seemed like they had a mind meld. Bob plays the role of Ham Salad in Ernie’s fantastic spoof movie Hardware Wars. Our songs were mostly introspective and about developing awareness. ‘The Time Is Here and Now’, ‘Tell Me Again’, ‘Misty Mind’, and ‘Nothing to Fear’ state their philosophy. The Kid fits right in with his ‘All Good Things’ and ‘Just Like Gold’. Both the positive side of living life as it is and the negative side of criticizing those ideologues who did not are present in the music. Musically, you can sense the minor sounding moods of ‘Bleeding Roses’ and the down sounding ‘Just Like Gold’. For me, part of the real inventiveness was Ernie’s unique harmonica playing and his tinkly, ringly, raga esque guitar style. And we do not forget the Kid’s contributions.

The great days of the Haight were from 1964 to 1966. From the time I moved there, as I have said, it was a colony of outsiders, artists, and college students distancing themselves from the conformities and strictures of the 1950s. A Hard Day’s Night was released in July 1964. With the Beatles’ free spirited behavior and their mocking of convention, this fit right in with what we were doing and thinking, a sense of generational solidarity. I must have seen it ten times between July and September, as did many of my friends. That solidarity ultimately became the flower children and the world youth revolution of 1968.

More and more groups were starting up, and some became very popular, even getting record contracts. The Haight started showing its true nature with the new Psychedelic Shop, the Oracle, and the Print Mint. Media attention mushroomed and brought hundreds of youth, then thousands. Haight Street became one way, always clogged with cars and crowded with street people and tour buses, adding to the insanity. This was all an explosion we did not appreciate or bother with.

We all felt ourselves to be outside of the hippie scene since, as artists, and I as a student, we were following our own paths. I focused on my classes and other interests at State. We, the baby boomers born in the 1940s, were now being invaded by flower children born in the 1950s. To be sure, some people’s motives were on the right track. They wanted to bring and share their artistic talents and expand their experiences. But the overwhelming majority had been uninformed and pushed by media hype. Bob and Ernie were too idiosyncratic and moved elsewhere, Ernie to 17th Street above Market.

Here are the words to one of Ernie’s early songs, ‘Walking Alone’ from 1965, which we performed but later dropped. I think you will get the idea. Incidentally, this was the very first arrangement I did for the New Age Band, later Orchestra.

Walking Alone

Carl Ernst Fossilius

First verse:

Walking, walking alone

Walking out on everything I have known

For if I stayed

I would die every day

I must go and find my way

Second verse missing

Bridge:

Walking alone

My mind is free

And the air is fresh and clear

The past and the future

Mean nothing to me

The moon is bright and life is here

‘The Time Is Here and Now’ is a propulsive, energetic track. When you listen back to it, does it bring you back to that specific moment on stage? Can you describe the kind of energy the band generated during your live performances?

Yes! Every time I hear it, it is like the first time. I felt it was our real anthem because it reflected everything we lived and felt in our daily lives. I was enthusiastic about everything connected with the song, and I wanted to show it. I wanted to punch the rhythm along. So from the great semi Byrds sounding beginning, I did not just hit the snare drum on the afterbeat, but on every beat instead. In my usual spur of the moment playing, I think I was directly copying the drum part from ‘Uptight (Everything’s All Right)’ from 1965 by Stevie Wonder, since it was popular that week and was also about the same tempo. This style of drumming was then not uncommon in the pop hits of the day. You can hear it on ‘Oh, Pretty Woman’ from 1964 by Roy Orbison, but also on many Motown hits such as those by The Four Tops: ‘I Can’t Help Myself’ and ‘The Same Old Song’ from 1965, ‘Bernadette’ from 1967, and Martha and the Vandellas’ ‘Nowhere to Run’ from 1965.

As for reaction, ‘The Star Spangled Banner’, which we called ‘America, America’, was our response to America’s policies of cold war paranoia in Vietnam. It delighted and amused listeners as a skewed, messed up version of current American life, especially at The Fillmore. Most of us were not political activists, but we surely did not approve of the War, especially in countering it by espousing and trying to live a turned on life of peaceful coexistence. Fans were into our philosophical songs like ‘Tell Me Again’ and ‘Misty Mind’ at the Fillmore. Most other places the band played, the Haight Levels, The Matrix, the San Francisco Art Institute, The Red Dog Saloon, and the Fox Plaza, were not dance venues. But when they played at The Ark in December to an overflow dance crowd, the response was electric, especially to their longer guitar and bass centered numbers like ‘Misty Mind’, ‘Blacklash’, and the powerful eight minute version of the psychedelic ‘Nothing to Fear’. The band with Jerry Slick was really tight and hot then.

The band broke up before the Summer of Love even began. What led to that decision, and what did you and the other members go on to do?

First of all, as Ernie has mentioned in our album notes, the group did not have a strong, super business like dynamic manager like Danny Rifkin or Chet Helms. Gigs were far between. Secondly, all of us had long been disaffected and disenchanted by the ruination of the Haight Ashbury caused by the media. Every block of Haight Street was crammed with squatters, runaways, or street people who had answered the media’s call. It had now become a one way street, with Grey Line sightseeing tour buses going up Haight explaining how hippies lived. A depressing environment, except for the enthusiasm of the audiences the group played to. Third, and I am guessing here, Ernie and Bob were probably getting bored, since they had no new material, except for ‘Grimly Forming’ and ‘Blacklash’, and probably wanted to get back into filmmaking and other personal projects.

I kept going to SF State. I finished my B.A. in American Studies and went on to get a California State Teaching Credential, and ultimately started my student teaching at Tamalpais High School in Mill Valley. I continued to make up songs with Ernie and the Kid separately during 1967-68. I would go to their flats and participate in their making reel to reel tapes, including Ernie’s ‘Paranoia Symphony’ from 1967 and the ‘Virginia City Summer Symphony’ from 1967, about our adventures while playing at the Red Dog there.

In 1968, the Kid and I started a new group, “Revolution,” basically a trio with Bob Hodges, my ex girlfriend’s brother, playing bass. The Kid wrote twelve songs, copies of which I have, for the group, which at one time included a guy and his wife, but they were not on the Kid’s wavelength. So they did not last past the Sexual Freedom League’s dance orgy we played for.

In 1969, Jerry, Bob, and Ernie were involved in animation and music for a new program that would start on PBS in the fall called ‘Sesame Street’. Grace Slick did the vocals for the Jazz Numbers series. Jerry went on to a career in filmmaking. See information about his later career on the Internet.

Meanwhile, in addition to his private eccentricities, Ernie has carved out for himself a successful career in the world of professional major films in various capacities, including editing and doing voice overs. I do not want to shock you, but his thirteen minute spoof film Hardware Wars from 1978, made for eight thousand dollars in San Francisco, has grossed over one million dollars. It features Bob Knickerbocker as Ham Salad. You can still find the local Oakland TV Creature Features segment with Bob Wilkins where Ernie is hawking his Hardware Wars merchandise, including the three colored metal lunch box, toothpaste, and Hardware Wars deodorant, his typical dry, offbeat humor.

Bob married Jane Dornacker, who had been with us since the beginning but had never played in the group. She was represented as a plaster torso. She and Bob unfortunately died in 1986. In fact, at the end of that year, while my family and I were living in Japan, I heard the final broadcast of her helicopter crash, she was a traffic reporter in New York then, replayed over Armed Forces Radio. I still have a tape I made of her playing the piano and singing a couple of her songs back in 1967. Also, I have a copy of ‘Rock and Roll Weirdos’ and ‘Pyramid Power’ by her group Leila and the Snakes.

Let’s talk about the incredible journey of this release. For decades, these tapes were thought to be lost to time. How did High Moon Records get involved, and what was it like for you to hear these recordings for the first time in so many years?

The tapes were never lost. I had them, or at least copies that Bob had given me. In 1984, I loaned them to a classmate of mine from Petaluma High School, Bill Combs, who made bootleg CDs. This was long before the Internet existed widespread; initially it was called the information highway. Years later, probably in 2006-07, after the Internet had really kicked in, while I was still working at Treasure Island Job Corps, another teacher, James Kramer, gave me a copy of ‘Trashbox’, apparently from ‘Pebbles’ from the UK, that had five CDs of wild psychotic garage punk. One of those included the full version of The Final Solution’s ‘So Long, Goodbye’. There was also a brief bio of us with our names misspelled. By 2008, Final Solution songs started appearing on YouTube, with pictures of The Haight Levels poster, our Berkeley Grateful Dead poster, or the Sausalito Ark’s ‘Gathering of the Tribes’ poster from December 1966.

Then in 2009, Kramer, as everyone called him, asked me to go with him to the grand opening of the Museum of Music and Design (the “rock and roll museum” he called it) in San Francisco’s Civic Center, emceed by an Alec Palao. Actually, I already owned a copy of Alec’s amazing book, ‘Love is the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets 1965-1970’ (Rhino Entertainment 2007), which not only contained hundreds of pictures, but had complete descriptions of over 70 different Bay Area groups and sample recordings, with four CDs included that contained all those songs. I was eager to go, if just to get Alec’s autograph for his book, which I brought in a bag with pictures of our group (we weren’t in Alec’s book). At first, we couldn’t get in as we had no purchased tickets, so we just sat outside next to Ron Nagle of The Mystery Trend. I asked him if he had seen Ernie lately, but he hadn’t, since Ernie was so reclusive.

Later, we were let in anyway and saw Alec introduce the acts. The museum displayed clothes worn by Janis Joplin and others in sealed cases, music posters on the wall, and various other memorabilia all over the huge room. I think Sal Valentino and some others from former San Francisco groups performed. So did Alec, who played the bass guitar to accompany Ron Nagle at his electric piano playing and singing ‘Johnny Was a Good Boy’ (1967), the amazing record by The Mystery Trend. Ron admitted that the song was ‘inspired’ by the case of Charles Whitman, the ‘Texas Tower Sniper,’ who, after killing his wife and mother, killed seventeen people from a university tower using multiple weapons in 1966. This was also the basis of the 1968 film Targets starring Boris Karloff with Tim O’Kelly as the sniper. The Mystery Trend’s album, ‘So Glad I Found You,’ was finally released in 1999. So The Final Solution has finally followed in their creaky footsteps.

Meanwhile, I walked up to Alec and identified myself as the drummer for The Final Solution and asked him to autograph his book. He was pleasantly surprised, since he knew of our group, signed my copy, gave me his card, and, if I’m remembering this right, said he would get in touch with me. He did. He came over to my house in San Francisco in June 2022 just when I was going through all my stuff and preparing to move to Kahului, Hawaii, where I was going to live near my daughter Kristina, her husband, and two children. I had long since put The Final Solution’s music on cassettes and my computer, so I gave Alec the Matrix and Pine Street reel-to-reel tapes, and maybe some others, including a reel-to-reel tape of Revolution, a group the Kid and I formed in 1968, and maybe a cassette with Ernie’s music and one of Jane Dornacker singing a couple of songs. He took me to lunch at my favorite Japanese restaurant nearby, and boom. Two years later, he contacted me here in Hawaii to write notes for the upcoming album ‘Just Like Gold.’ And bingo, now here we are.

Frankly, playing the ‘Just Like Gold’ CD is like hearing the music for the first time. As I was always a fan of The Final Solution and their music, not just my drum playing, I continued listening to the songs countless times over the years, usually once a year, and now here I am at 81. But what Alec and Dan Hersch have done in remastering the tapes is staggering. I am always overwhelmed listening to it. I even hear myself singing and playing parts I had never heard before. The sound is all so deep, sharp, and clear. It sounds like it was recorded in a studio or from a live broadcast on very expensive sound equipment. It all sounds more professionally done. The blending of the instruments is amazing; the added depth to the sound is remarkable. Whatever technical magic and wizardry you performed gives the songs a richer, fuller sound. The track selections on the LP now give a great sonic picture of the free-time lifestyles of those early Haight Ashbury days. I am so blessed to have this wonderful gift of love from Alec. I cannot thank you enough.

Now that the music is out there, have you reconnected with the other surviving members of the band? What has that experience been like?

Ernie is hard to reach. I have not heard from him yet. Maybe if I “threaten” to release some of his early tapes, he might call me, just kidding. Bob is long dead, and the Kid, probably as well. Jerry Slick passed away in 2020 after a strong career in making promotional videos. I need to say a little about Bill Brach, the main photographer of almost all of our album photos. I think Herb Greene took one or two. After the group broke up, I became good friends with “Brach,” as we always called him. We would hang out at his or my place to listen to or play music, and often played Hex, a three-person chess game, with a mutual friend who had designed it. I think we drove up to The Inn of the Beginning in Cotati, California, to see Clifton Chenier or Dan Hicks and his Hot Licks. Brach now lives in New Mexico. I think I will call him tomorrow. My only other contacts lately have been with the ‘shadowy’ figure Don Johns and Richard Falvey, who used to play and sing piano duets with Jane Dornacker. Naomi, Bob and Jane’s daughter, is grown up now and maintains an active and passionate presence on Facebook regarding international political issues. And me, well, it is back to the beach in Kihei.

If you could go back to that night in July 1966, what would you say to your younger self on that stage at The Matrix?

Well, as you can tell from my recollections here, I was not a major or even a minor player in the history of the Haight Ashbury. I never took the Acid Test, hung out with the Merry Pranksters, flaked out on Hippie Hill, never jammed at 1090 Page, since we were busy with our own overflowed parties at 1732 Page, nor did I go to the “Summer of Love.” Well, I did go to the Human Be-In and later to the Fillmore to watch and hear The Doors. I was mostly a student. I was a dot, a speck, just dust in the wind. Now, sitting here in the far future from then, with “the ashes of time burned away” (Lightning, Suzanne Vega / Philip Glass 1986), what would I say to my younger self? Could I have changed anything by saying ‘stick with the band and make sure you all get to LA to record’? Would life have turned out differently or not? Is it the result of free will or determinism? Are there multiple timelines, like strands of spaghetti coming out of a box from a single central point? Would I never have a career teaching English? Well, I did, it turns out. Looks like it has all been determinism, at least until I can find a wormhole that takes me to an alternate reality.

Do you want to know about the present perfect tense? That is easy. You are. I am. Everyone is: started in the past and continues into the present and future. The same applies for the present perfect continuous: “I’ve been living on Maui for the past three years and will continue to be so doing. See you on the beach in Kihei sometime!”

P.S. Thanks for the opportunity to participate in this interview. It has really taken me back as well.

What do you hope people take away from listening to this album? What do you see as the band’s legacy?

For me, the amazing technical wizardry that so beautifully enhances the album’s music creates a sonic picture for listeners of exactly what it was like to be in the Haight Ashbury then. Our music in theme and content was a part of the Zeitgeist of that era. I guess you could say it came out of the culture, everybody sharing the same way of life and thought. It was a time of a new change in consciousness, which ultimately led to the massive upheaval and influx of alienated, disillusioned, and media-fed American youth from all across the country.

I just found a quotation from the poet Allen Cohen, who sums it all up very well. He died in 2004, with his place in Haight Ashbury’s history a little underappreciated. This is from the CD-ROM Haight Ashbury in the Sixties, Part 3 (available from www.rocument.com/haight):

“The beat and hippie movements brought the creativity of an anarchistic artistic subculture and a secret and ancient tradition of transcendental and esoteric knowledge and experience into the mainstream of cultural awareness. It gave us back the sense of being originators of our lives and social forms instead of the hapless robot receptors of a dull and determined conformity. The freedoms that became real to us have not been beaten back. The values of compassion, creativity, social equality and love and peace will be victorious over war, fear, control and injustice. It is up to each of us to work together in creating a world that will survive and flourish.”

Well, as an old hippie myself, my style may have changed, but not the mission. As the world continues moving towards transhumanism and the Singularity, I hope that our music’s legacy will be to help get you a little high, psychedelicized, and seeing yourself as the originator of your own life.

The time is here and now.

It just is.

Klemen Breznikar

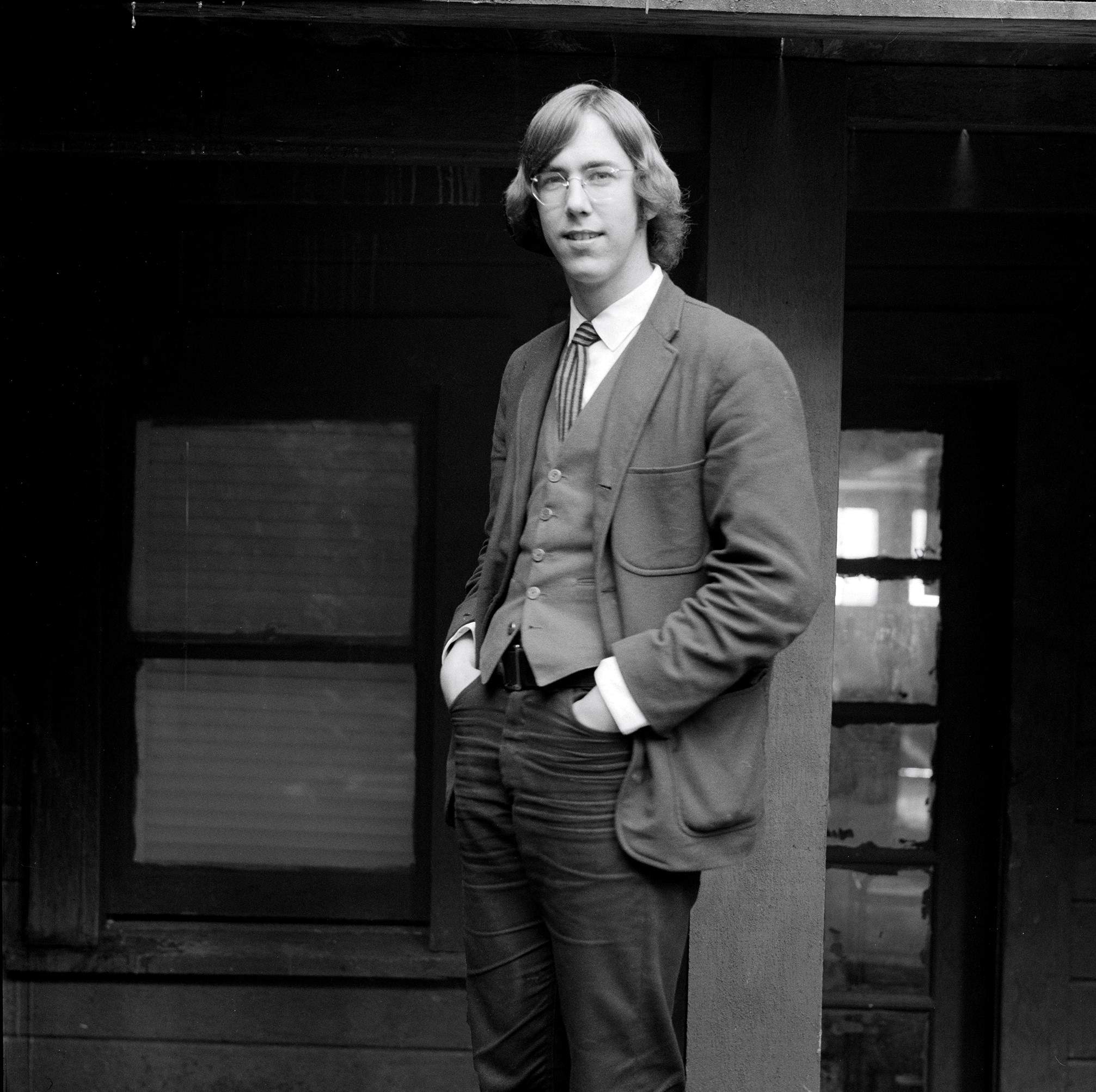

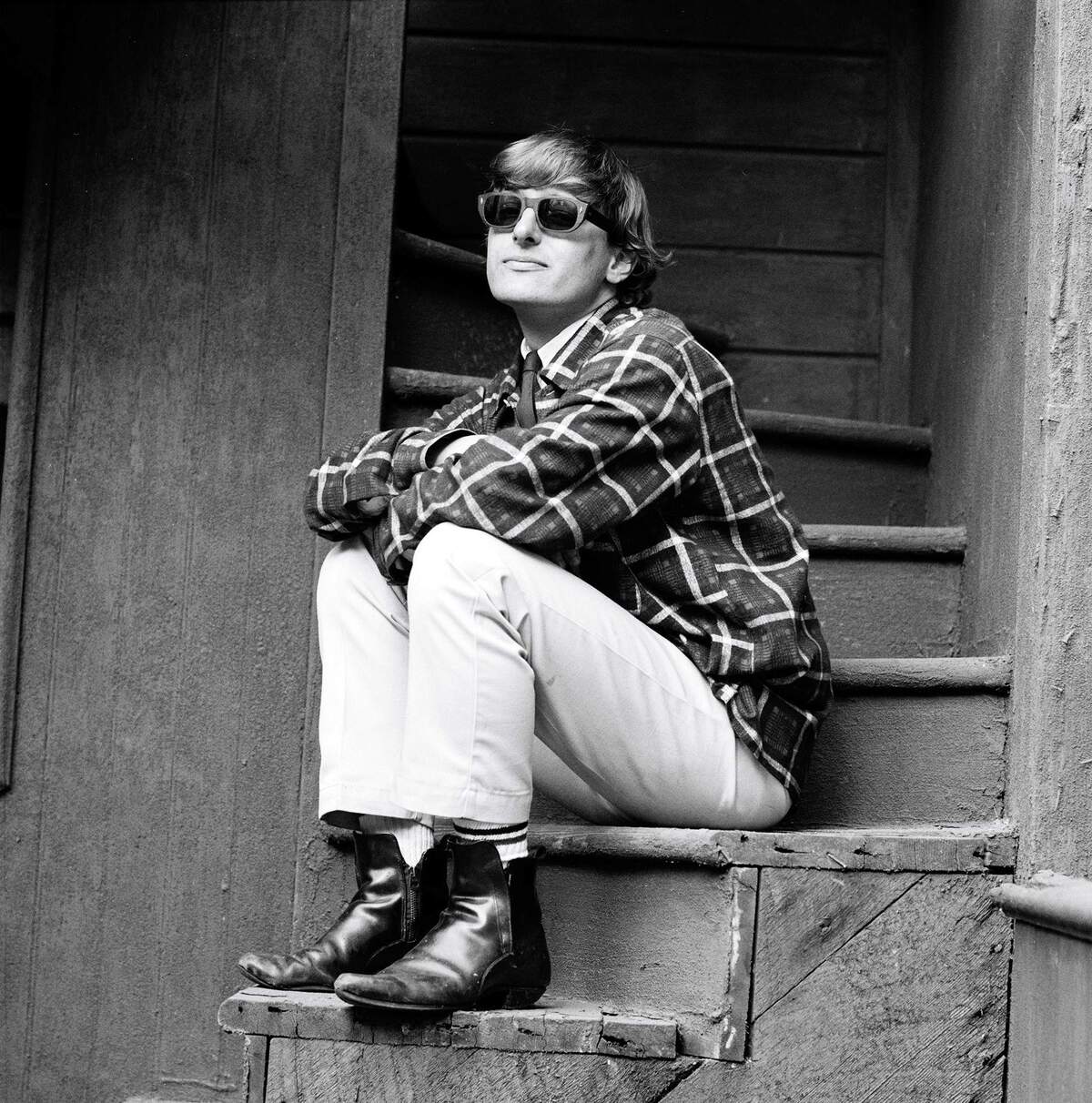

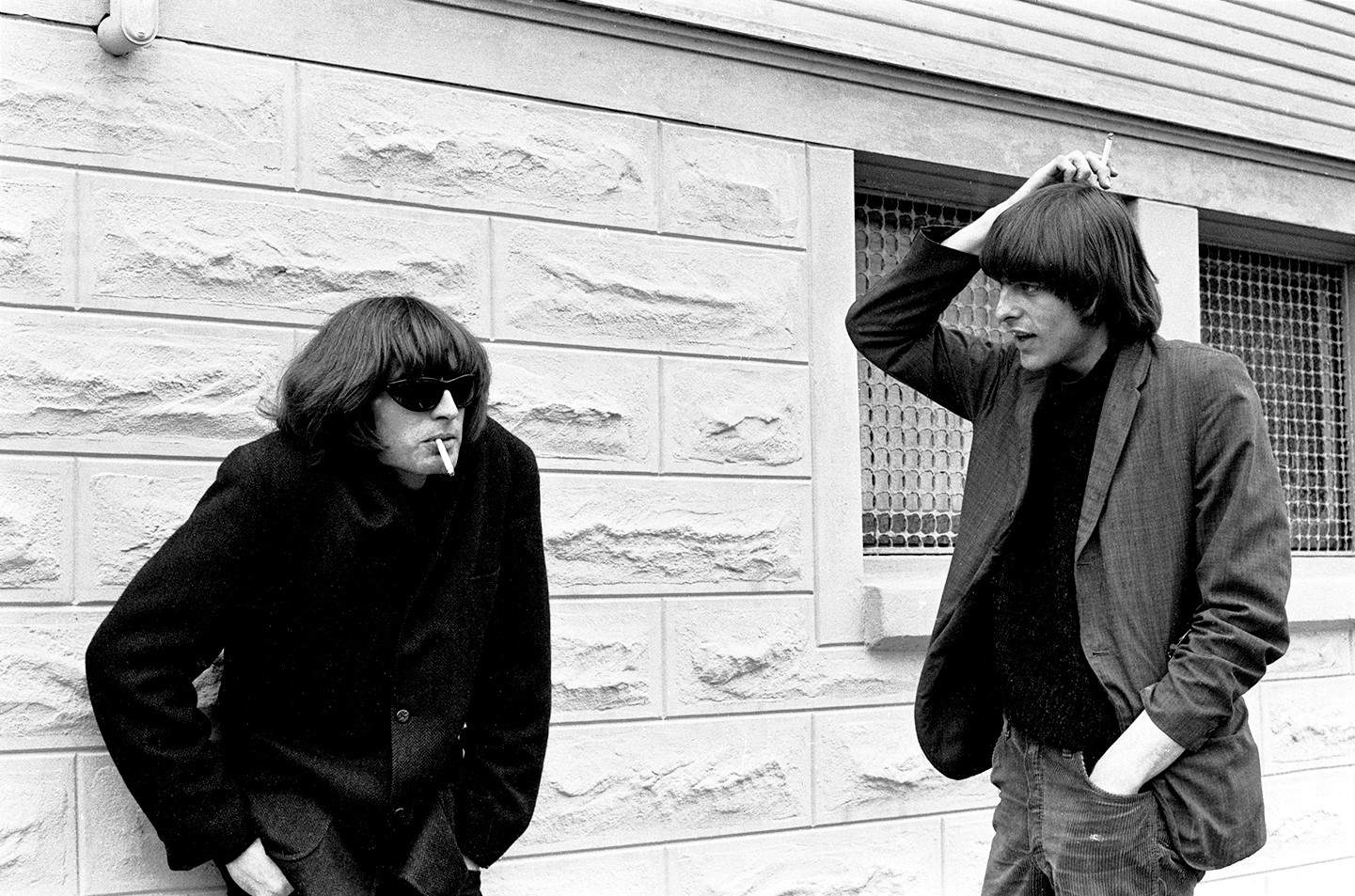

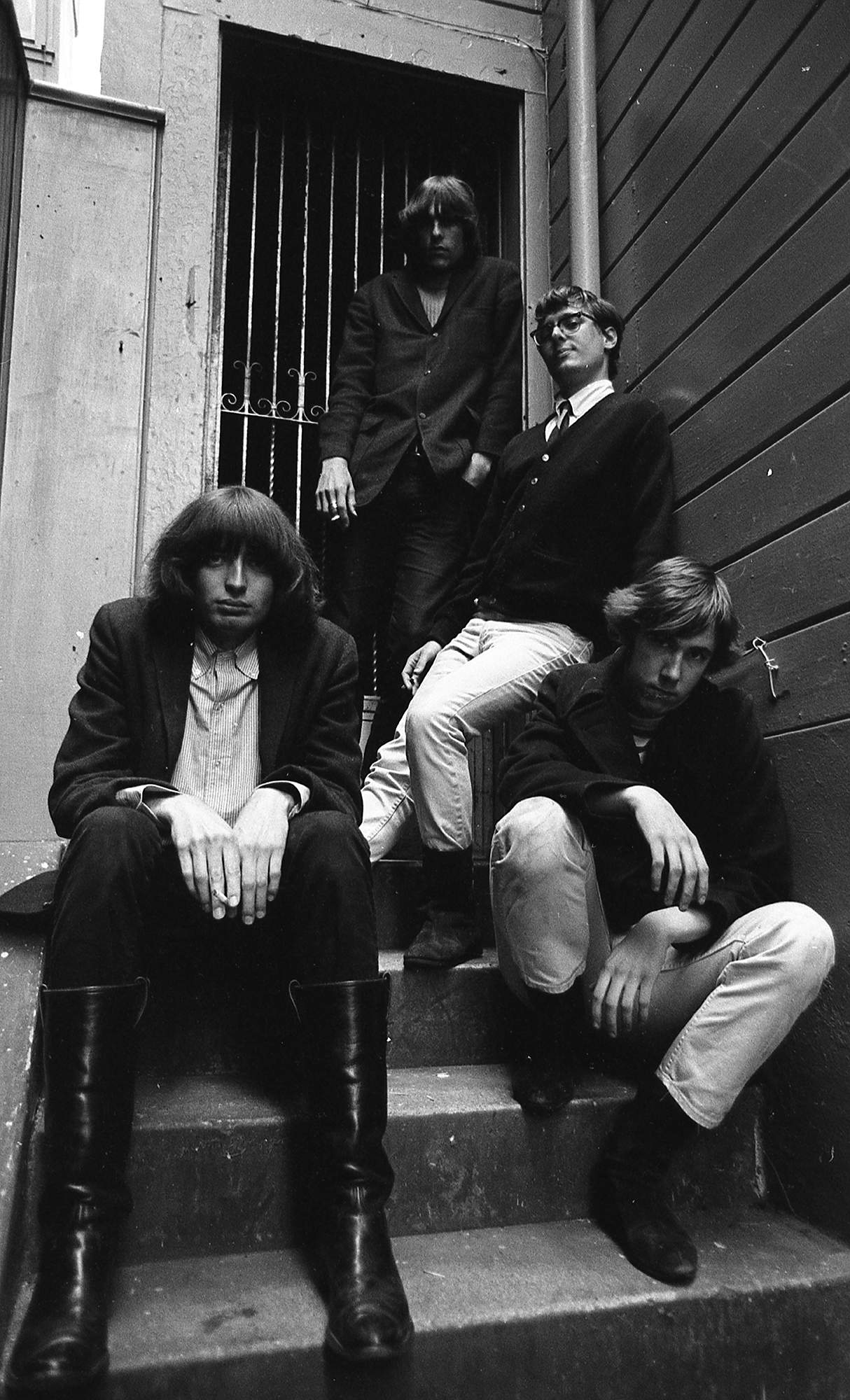

Headline photo: The Final Solution (Group L to R: John Yager, Ernie Fosselius, John Chance, Bob Knickerbocker) (Photo by Bill-Brach)

My Memory Joggers

Chance, John. 1964-1969. Personal Journals.

Dylan, Bob. 2003. The Essential Bob Dylan Songbook. Project editors Giller, Don and Lozano, Ed. Amsco Publications, New York.

Johns, Don. 2025. Personal Communications.

Miles, Barry. 2005. Hippie. Sterling Publishing, New York. [A huge book of photos!]

Palao, Alec. 2007. Love is But the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets 1965-1970. Rhino Entertainment Co., Burbank, CA.

Perry, Charles. 2005. The Haight Ashbury: A History. Wenner Books, New York.

Sculatti, Gene and Seay, David. 1985. San Francisco Nights: The Psychedelic Music Trip 1965-1968. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Selvin, Joel. 1994. Summer of Love: The Inside Story of LSD, Rock and Roll, Free Love and High Times in the West. Dutton, USA.

Suggested Videos

Cohen, Allen and Donahue, Rachel. 1995. Haight Ashbury in the Sixties. (www.rocument.com/haight)

Cohen, Leonard. 2009. The Tibetan Book of the Dead: A Way of Life, The Great Liberation. Documentary DVD (available from Amazon)

High Moon Records Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube / Bandcamp

I first read the name of this great band as it was mentioned in Ralph J. Gleasons book “The Jefferson Airplane and the San Francisco Sound” that I purchased in 1969 but never heard a recording up to now … and I love the album

Thanks for the interesting interview. I got the Matrix recordings on a cassette from the USA in the late 70s. Later it was rel. on Curiosities S. F. Underground Vol. 2. I still have a tape S.F. PAGE STREET 66 or 67.

GREAT – MUCH BETTER QUALITY THAN MY OLD TAPE !!!

Wow what a recollection of the 60s! Awesome.