Surfers’ Chaos and Paul Leary on the New ‘Live at the Leather Fly’ Release

Few bands have embodied chaos as eloquently or as viscerally as Butthole Surfers. Formed in the early ’80s by Gibby Haynes and Paul Leary in San Antonio, they surfed a molten wave of acid-fried punk, performance art, noise freakouts, and dadaist humor into a legacy that still feels totally untouchable.

‘Live at the Leather Fly,’ out May 9 via Sunset Blvd., really captures them at their most wild and unpredictable. The recording, long buried and of dubious origin, seems less like a document and more like a hallucination: 21 tracks of completely off-the-rails psych-punk, warped through the band’s twisted Texas lens. The opener ‘Graveyard kind’ of stumbles in like a zombified blues jam before collapsing into glorious sludge. ‘The Annoying Song’ is pure chaos, with Gibby shouting through a toy megaphone—a trick born on the Lollapalooza ’91 tour and now preserved here in all its noisy glory. And yeah, ‘The Leather Fly’? Never existed. But that’s part of the magic. The Surfers never played by the rules, so why start now?

And hey, we also got to sit down with Paul Leary for a rare and surprisingly deep chat. He shared some amazing things for the very first time. Paul reveals that in the early days, while recording their first EP without a drummer, a strange guy in disco platform shoes knocked on the studio door, played each drum part separately, starting with the hi-hat, and then left—never to be seen again. They never even got his name. You’ll definitely want to read it.

“We started in chaos and evolved into music.”

Back in the ‘80s, the idea of ‘The Leather Fly’ was just a fantasy, a private joke between you. Now it’s the name of a live album, an artifact pulled from some hazy corner of Butthole Surfers lore. If ‘The Leather Fly’ had actually existed, what would’ve been its defining feature—something that no other club would dare to have?

Paul Leary: ‘The Leather Fly’ was something we referred to a lot, although it never existed. ‘Live at The Leather Fly’ was almost a battle cry whenever we came up with another stupid band name. If ‘The Leather Fly’ had actually existed, its only defining feature would have been a stuffed leather fly.

‘The Annoying Song’ started as a joke, but you ran with it until it became something real. That seems to be a recurring pattern… taking something ridiculous and pushing it so far that it transcends absurdity. Is there a specific moment in the band’s history where you realized that the most off-the-wall ideas were the ones that actually worked?

The most stupid ideas always worked with us. We didn’t care if they worked for anyone else. We aren’t the brightest bulbs. We stayed in our lane and did what we were able to do.

The origins of this recording are apparently lost to time. If you had to invent a completely false but convincing backstory for ‘Live at the Leather Fly,’ what would it be? Where was it recorded, who was there, and what was happening in the room that night?

Fantasy is an important element in rock music. It is important for listeners to be able to construct their own backstories. That’s what I do when I listen to music. When songwriters explain their music, it’s always a disappointment.

Texas has this deep weirdness to it… from psychedelic rock, outlaw country, punk, to all kinds of mutant strains in between. Do you think Butthole Surfers could have formed anywhere else, or was Texas an essential ingredient in the madness?

No, Butthole Surfers could not have formed anywhere else. The music scene here was so not part of the whole East Coast/West Coast thing. The Texas scene was a red-headed stepchild.

There’s a long history of bands getting labeled as “performance art” when things get too weird for people to comfortably call it rock music. Did you ever see what you were doing onstage as something more than a rock show, or did it just naturally evolve into chaos?

We started in chaos and evolved into music. Our earliest shows were in an art gallery in San Antonio. Music was an excuse to do stupid things on stage, come up with stupid band names, and make stupid album covers.

At some point, you must have realized that manipulating sound—warping vocals, distorting guitars, messing with tape loops—wasn’t just an effect but a core part of your identity. What’s the single most demented, wrong-sounding, yet somehow perfect sound you’ve ever captured on a recording?

The first thing this question brings to my mind was the recording of our song ’22 Going On 23.’ We were living in Winterville, Georgia, outside of Athens, and we had set up recording equipment in the living room of the house we were renting. One night I couldn’t sleep. While everyone else was sleeping, I really wanted to record something, but I didn’t want to wake people up. I had a small transistor radio, so I decided to put a microphone in front of it and turn it on. Immediately this woman’s voice came over the air, describing her horrible life. I hit “record” on the tape machine as fast as I could, and got vocals for a song that didn’t exist yet. The next morning the bass line just came naturally, and everything else fell into place. It was all wrong and perfect at the same time.

You’ve played in places that range from total dumps to festival stages with professional lighting rigs. Is there a particular show where the environment itself—whether it was the venue, the crowd, or just a general sense of doom—completely changed the way you played that night?

We pretty much carried the important elements of our light show around with us. We had 16-millimeter film projectors shining scenes of genital reconstruction and car wrecks and nature scenes all at once. We would blast all of our smoke machines at once near the end of the show, and the projectionist would pull back on the focus so that the image remained sharp and in focus on the smoke cloud as it billowed out into the audience. It was a pretty cool effect. We carried an entire back wall of airport-grade strobe lights that would flash bright enough so that if you put your hands in front of your eyes you could see the veins and bones. Then Gibby would fill an upside-down cymbal with alcohol and light it on fire. When he hit it, a mushroom ball of flame would result. I can’t believe we never burned a venue down. But, to answer your question, I don’t recall a single night where anything completely changed the way we played that night. Although we did play one show at The Danceteria in NYC… We were booked to play two shows that weekend, and we came all the way from Los Angeles to do them. When we arrived, they changed it to one show. We were pissed. Never would have driven all that way for one show. The bedlam we unleashed that night was epic. It gets screen time in our upcoming documentary.

Butthole Surfers have always had an aggressive relationship with the industry—you were on Touch and Go, Rough Trade, Capitol, and even had a major label bidding war over you at one point. Looking back, was there ever a moment when you were tempted to just go fully corporate, or did it always feel like a ridiculous game you were playing from the inside?

In my mind, we did go completely corporate. Signing with Capitol Records was the cherry on top of everything we had accomplished up to that point. We were on the same label as The Beatles, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Grand Funk Railroad. Not bad for an absurd band. We could not have scripted it any better than that.

There’s a very specific kind of tension in your music—like it’s constantly swinging between total chaos and something strangely catchy. How do you know when a song needs to be a complete freakout versus when it needs a hook?

The songs took care of all that. We were proud to present a schizophrenic array of songs on our albums. Song ideas fell from the sky, and we let them go where they wanted to go.

“I was out to punish the world with my music”

Your early albums were crawling with strange voices, tape loops, and cut-up samples, long before everyone had access to that kind of technology. Do you remember the first time you used a piece of studio gear in a completely unintended way and realized you’d just discovered a new sound?

We were listening to a lot of fucked up music at the time, so I never thought we were discovering any new sounds. Personally, I was out to punish the world with my music. I was angry and bitter about not getting a job as a stockbroker.

There was a show in the ‘80s where you projected a film of a penis surgery onstage while playing. What was the thought process behind that? Was it an experiment in confrontation, or were you just seeing how far you could push an audience?

We weren’t trying to push the audience, although we pushed a lot of people out the door during our shows. It was just what was in us to do. We didn’t put a lot of thought into anything. I remember one night in 1990 I went to sleep in front of the TV. I woke up at 2 in the morning to a broadcast of a band with billowing smoke and belching flames and flashing lights… just total mayhem. And I thought, “Now that’s a rock show!” Then I realized it was us on the TV. I felt proud about that.

At Lollapalooza, you brought out shotguns filled with blanks and fired them off onstage. That’s not something you can just casually do without planning. What was the lead-up to that moment? Did anyone try to stop you?

Nobody ever stopped us from using the shotgun or the fire cymbal. Those blanks were actually pretty violent. They were much louder than real shells and were intended for training hunting dogs. You could shred a beer can from ten feet with them. It became common for a fire marshal to turn up before shows to inspect the shotgun and the fire cymbal, but nobody ever said no to using them. I cannot imagine getting away with those things today.

The song ‘Kuntz’ from ‘Locust Abortion Technician’ is built around a loop of a Thai pop song, turned into something completely sinister. How did you first discover that sample, and what drew you to that sound?

It’s not a loop, it’s the entire song from a cassette tape of Thai music. I ran it through an Ibanez rack-mount delay unit and went crazy with it. Probably the stupidest song we ever put out.

There’s a version of the band’s history that people know from the records, and then there’s the version that only exists in the memories of those who were there. What’s something from the Butthole Surfers’ past that’s never been documented but absolutely should be?

In our earliest days, before our first record came out, we had a lot of trouble getting drummers to play for us. Some would occasionally feel sorry enough for us to play a song or two. Gibby and I opened in Houston for TSOL as a two-piece. This was after our first drummer quit the band. We had a record deal but no drummer. We started recording our first EP without a drummer. We had a song called ‘Hey.’ One day in the studio there was a knock on the door, and this weird guy with disco platform shoes came in and announced that he was a drummer, and asked if he could play on a song. We were delighted, and he played drums on that song. He insisted on recording each drum one at a time, starting with the hi-hat. When he was done, he left. Never knew his name. Then King came along, and he was ready to throw down for the long haul. That was a real coup for us.

Klemen Breznikar

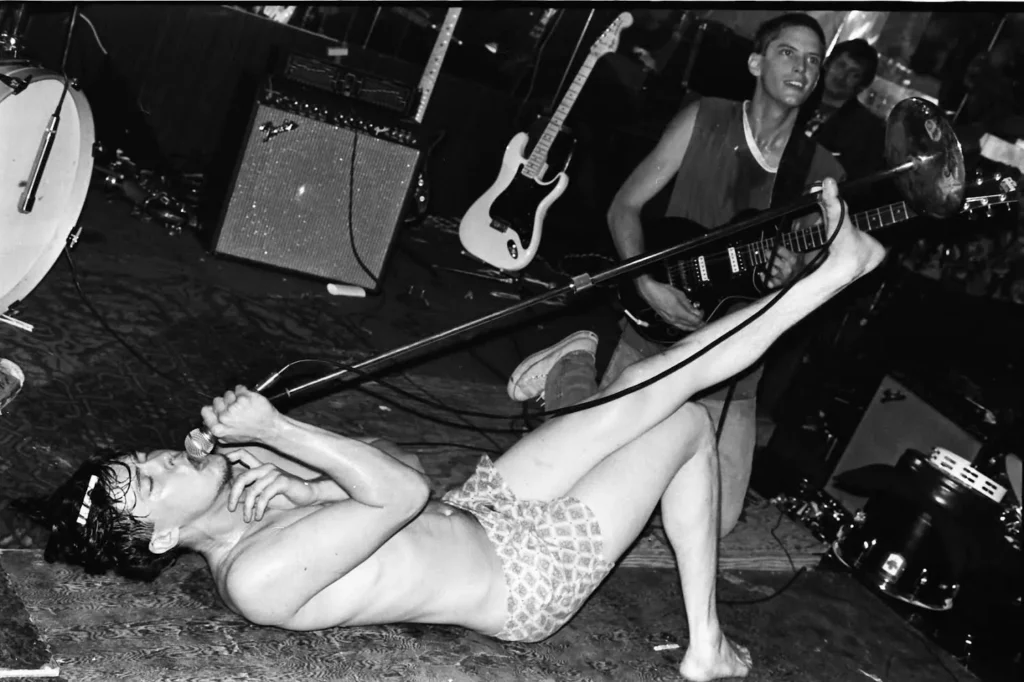

Headline photo: Butthole Surfers | Photo by Kirk R Tuck

Butthole Surfers Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube / Bandcamp

Paul Leary Facebook / Instagram / X

Sunset Blvd Records Website / Facebook / Instagram / YouTube / Bandcamp

‘The Birds Are Dying’ by Paul Leary | Butthole Surfers | Interview | ‘The History of Dogs’ Reissue + New Album, ‘Born Stupid’