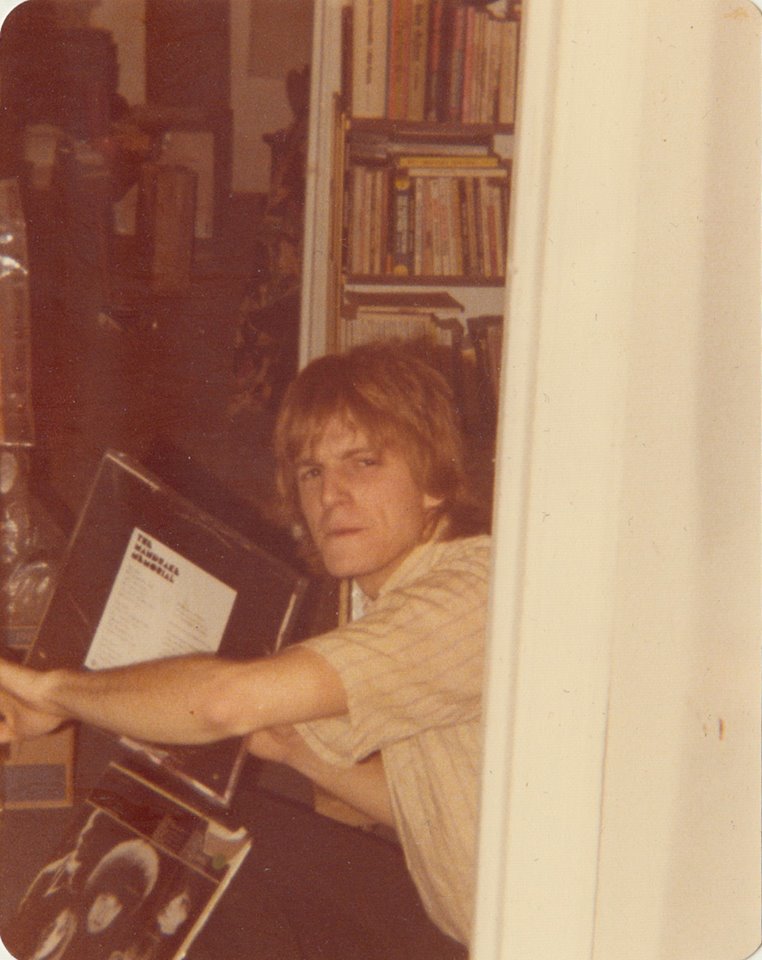

Interview with Wolf Roxon

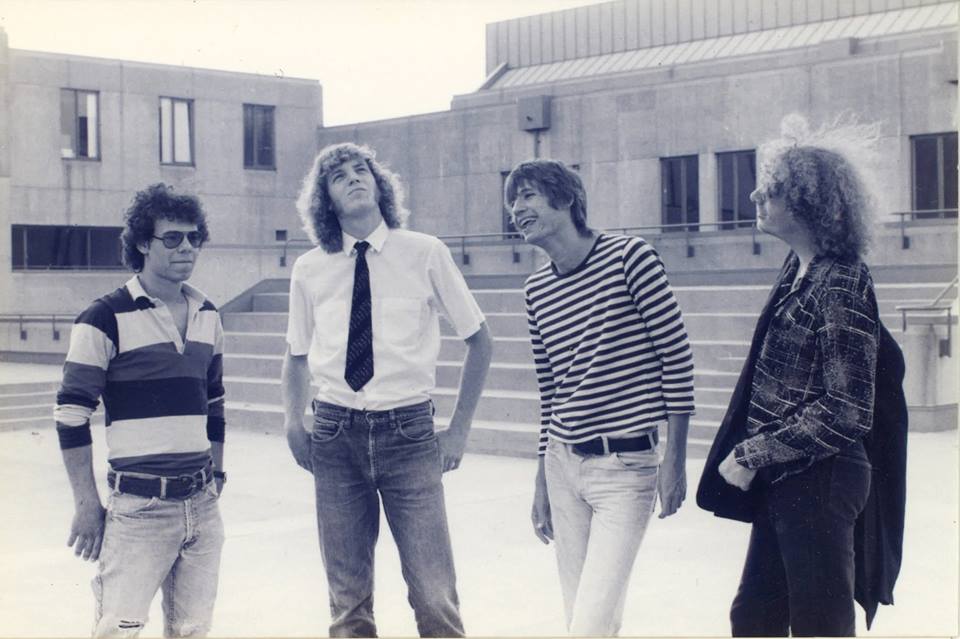

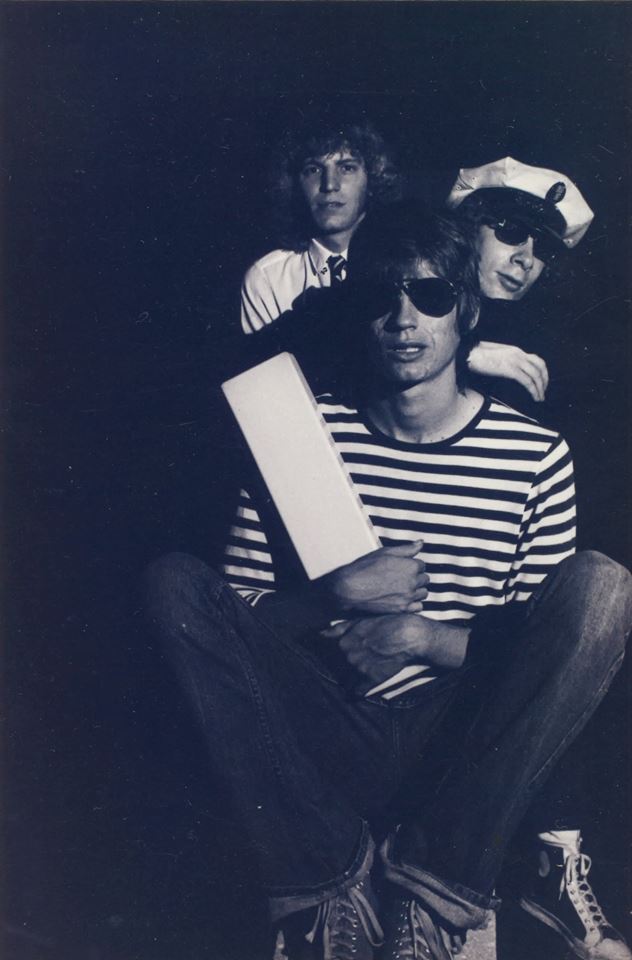

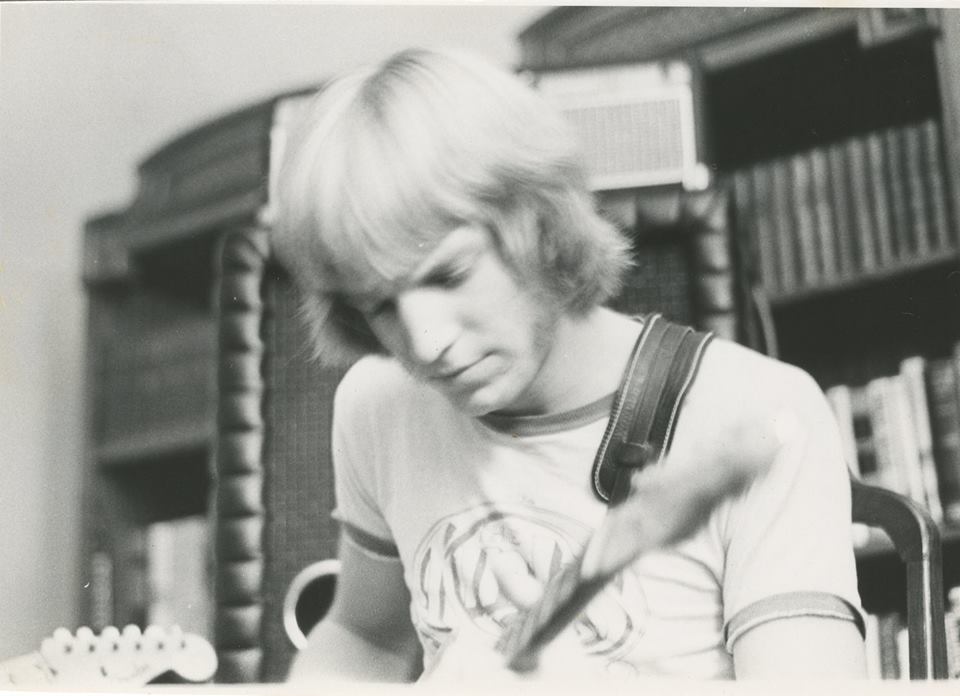

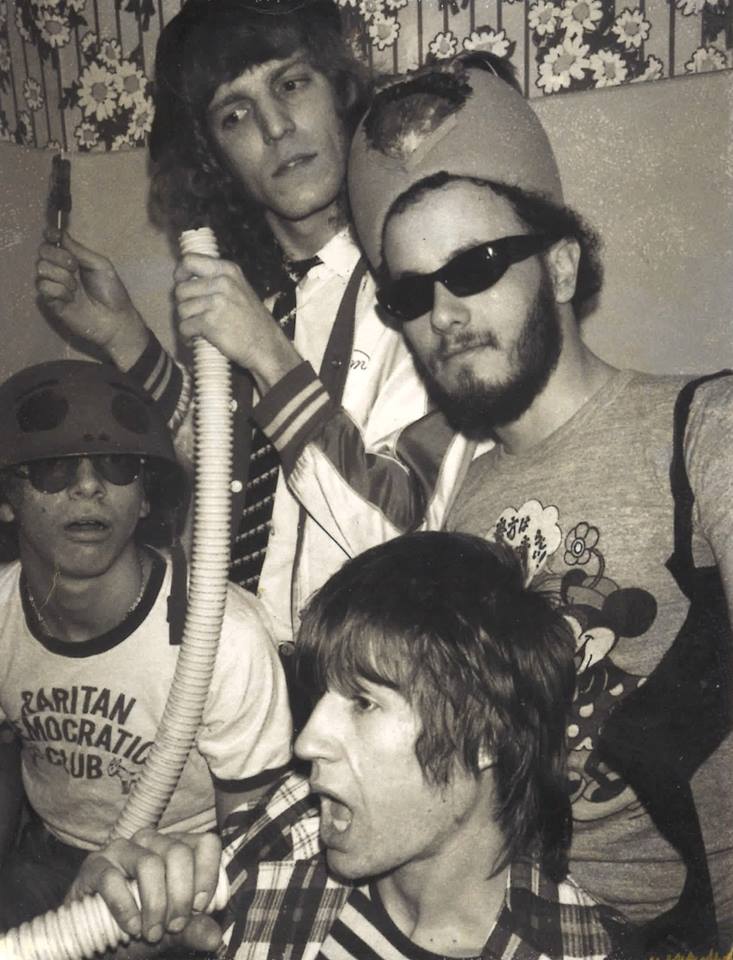

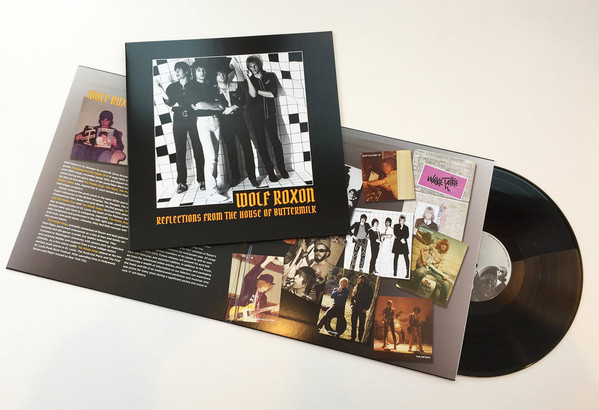

The Moldy Dogs were formed in the Fall of 1972 when Wolf Roxon met Paul Major while attending Webster College in St Louis. Wolf Roxon later on formed a lot of bands including The Tears, The Metros and Walkie Talkie and at the same time also started solo projects. He recently released Reflections From The House of Buttermilk, which I highly recommend!

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music?

I was born in St. Louis (Benton Park area) in 1952. While no one in my family attended a conservatory, we all enjoyed music. My Mother constantly sang as she worked around the house and my uncle played guitar during the Big Band Era and performed in a few local bands. Popular tunes were always a part of our family sing-a-longs. While Uncle George never taught me anything on guitar, my appreciation of the instrument started shortly after birth due to his influence.

When I was three years old, we moved to the suburbs in North St. Louis County. One evening, I accompanied my Father to a friend’s house who was showing off his new hi-fi sound system. He flipped on the radio and “Rock Around The Clock” erupted from a quality sound system. He claimed the song was “this new stuff called rock’n’roll,” as he snapped his fingers and stamped his foot. I followed his lead and moved various parts of my body like a fish on a musical hook—there was no escape.

Rock’n’roll and all its genres became a part of my life since that moment. Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, Richie Valens, and Buddy Holly were my early rock gods. Losing two of the five in one plane crash made for the worst day of my early childhood.

Having an older brother and sister also offered exposure to a wide variety of music. Both had slightly different tastes; so the folk movement, Brubeck, teenage boy idols, the Everly Brothers, and even show tunes entered my life.

We could not afford to buy anything related to music. Fortunately, we had some lucky breaks. When a neighbor owed my Mother money for babysitting, they offered to barter their extra hi-fi set instead. We had another neighbor who maintained jukeboxes. He gave us a few crates of records (45’s). These may appear to be minor events, but, for us, the record player and 45’s were manna from heaven. After all, God must be on our side—He gave us rock‘n’ roll, a record player and records. What more could we ask?

There was a local scene in the city of St. Louis in the 1950s-60s: Chuck Berry, Ike and Tina, and other future stars would perform in clubs along with other national/regional/local artists. Unfortunately, my Father left home shortly after our move to the suburbs and we had no car—so travel anywhere was difficult.

Chuck Berry was the only local St. Louis rocker to influence me, especially with his lyrical construction, descriptive language, strong verbs, and his tendency to offer slight vagueness by twisting and turning words and phrases. So Sweet Little Sixteen is “sportin’ ” high heel shoes and Marie (Memphis) has “hurry home drops on her cheeks”.

“No Particular Place To Go” is the textbook example where Berry deliberately packed every line with suggestive phrases, vagueness, and double entendres. His methodology forces you to consider the possibility that maybe there is something more going on in his poetry (songs) than one initially thought. Are his words to be taken literally or figuratively? His lyrics cause one to think and speculate. If that’s not enough, or too much, then just enjoy the tune’s kick ass rhythm and dance.

Chuck also legitimized the right to mispronounce words or add/subtract syllables in order to maintain rhyme schemes or rhythmic meter (he sings “a la cart tay” not a la carte—because he needed a four syllable word). Ray Davies, another of my mentors, used most of these same tactics.

All of Chuck’s techniques greatly influenced my writing. “Too much vagueness maketh a song” became my credo. Add a little imagery, create slick, new expressions that imply a meaning, and stick to the rhythm with your phrasing and the lyrics will fall into place. Of course, rock’n’roll was an infant when Berry was in his prime. By the time I was writing, both the world and music business had changed considerably, which has a habit of affecting artistic expression.

When did you begin playing music? What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

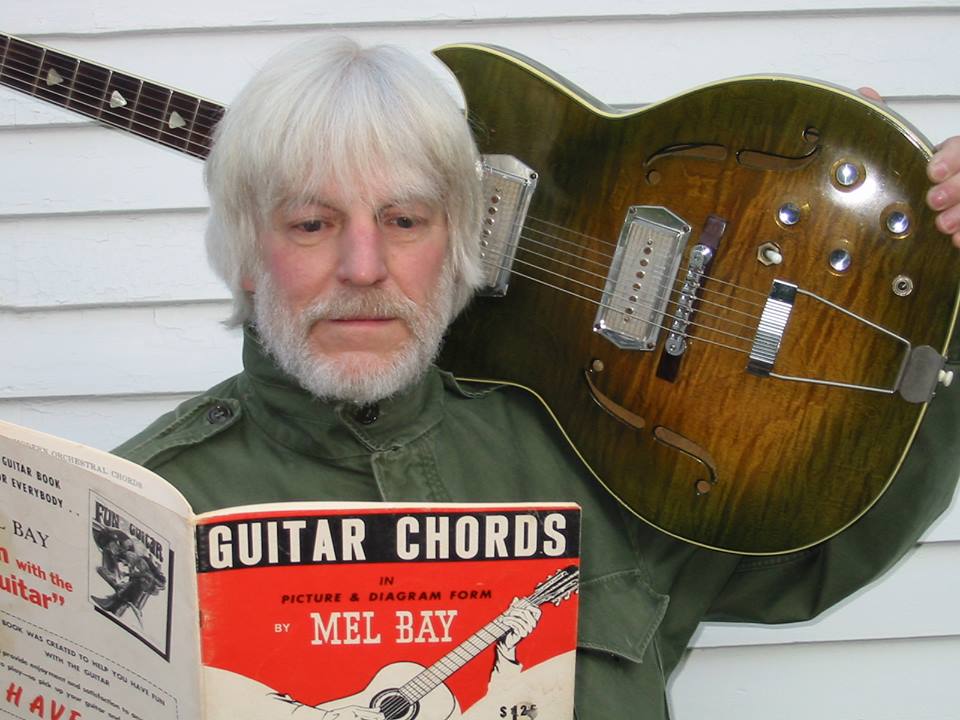

I started on ukulele in elementary school and graduated to guitar around 1963. However, this particular guitar (an Audition) was unplayable and I wasted years trying to finger notes and chords on a neck impossible to properly intonate.

I took lessons from an older woman who lived on my street. She focused on reading music, played only melody, refused to recognize the guitar as a rhythm instrument, and hated rock’n’roll. I dabbled a bit around my neighborhood with some other kids who also took lessons from the same woman. We basically reeked. My interest in performing music varied considerably until 1968 when I purchased a playable guitar (Custom Kraft—still cheap, but easy to finger and almost intonate).

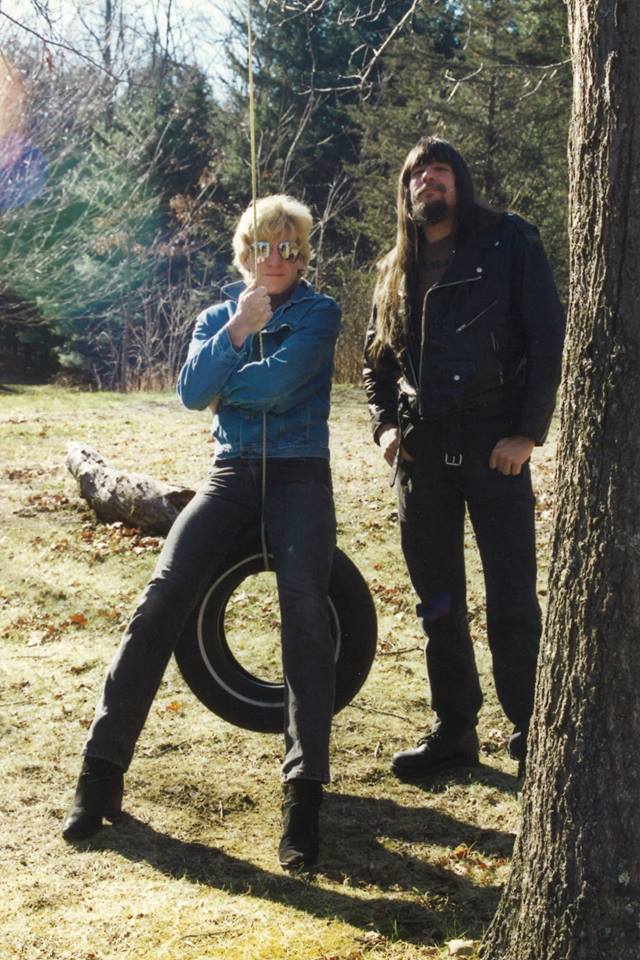

By the late 60s/early 70s, Jon Ashline and I (as Wolfgang and the Noble Oval) began writing and recording which sometimes included Bruce Cole (future Screamin’ Mee Mees) and another friend. As a foursome, we referred to ourselves as The Enamel Graveyard. We were pretty awful. Most listeners were offended when we offered our recordings for their listening pleasure. Soon after, I attended Webster College (St. Louis) and met Paul Major. Paul actually liked those “unlistenable” tapes. So we started jamming together and The Moldy Dogs were born.

Though Paul was already highly competent on guitar, we meshed as musical partners. My basic, solid, rhythm left room for Paul to toss in lots of lead fills, bass lines, and extended solos. I learned more from watching Paul than all those worthless lessons. What’s important to understand is that Paul and I always wanted to develop as musicians. We worked long, hard hours, especially after we graduated and had the time.

Even during our tenure in the NY punk scene, when bashing three-chord minimal rock was in vogue, I attended classes at The Guitar Study Center. Buying my first multi-track recorder (TEAC 3440-A) had a profound affect on my guitar skills. Now I had to figure out additional guitar arrangements. Sometimes Paul or Vic Harrison (another excellent guitarist) would offer help, but I often forced myself to write and play a bass part or guitar fill.

As a guitarist, my biggest influences were Mick Ronson, Dave Edmunds, Django Reinhardt, Davey Graham, John Renbourn, and Keith Richard (circa Beggar’s Banquet). As a songwriter, the entire British Invasion throughout the 1960s (especially The Kinks), Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, The Doors, Lou Reed, John Fogerty and Dylan were my mentors. Some obscure artists (or were obscure at the time) also inspired my creativity: Morgen, The Stooges, and any group represented on the Nuggets LP’s, especially the British compilation. Marc Bolan and, lastly, David Bowie were strong influences. After Bowie, there were no others. He took rocknroll as far as it can go.

I quit the music business in 1982 and seldom picked up a guitar until the mid- 1990s. In the early 2000s, I attended the International Guitar Seminars in NYC and studied with John Renbourn, Woody Mann and others. John taught me a lot, especially various fingerpicking techniques which added another dimension to my guitar work and augmented my solo performances.

Recording the Legend of the Lost in 2000 forced a tremendous effort in arranging guitar and vocals. The sixteen song CD required skills I never had in my earlier days. Now older, and having patience, I came to the realization just how much perseverance was necessary to produce a masterpiece. There were none on this CD, but I came close on a couple tracks.

I probably peaked as a guitarist in 2004-5. Since then, carpal tunnel and arthritis have slowed my progress, but I am still way ahead of those early years. Plus, my arranging skills have improved enormously.

What was the first song you ever composed?

We composed songs as far back as I can remember. Mad Magazine inspired us to write lyrics that fit well-known melodies. Two early creations, with both music and lyrics, were baseball tunes: one concerning my favorite team (New York Mets) and another about John Bocabella, a baseball player (Cubs), composed in 1963. John was hardly a sports icon, but that name really rocked—what rhythm!!

One of my favorites, “Andrea Pilcher”, a tune about a girl in my English class (written in 1966), was eventually rewritten and recorded (2002). The third verse is one of my finest.

By the late 1960s, most of my songs were immortalized on paper. They survived. So there’s little chance of losing the words to Eva Braun Spinning Round and the rest of the Wolfgang and the Noble Oval catalog. But most of those early ones are long forgotten, though I remember most of the verses to the New York Mets tune.

Can you elaborate the formation of The Moldy Dogs? How did you decide to use the name?

The Moldy Dogs were technically created on November 8, 1972 at Webster College (now Webster University). The date can be pinpointed with such accuracy because I had tickets to attend a Neil Young concert that evening and, when my girlfriend broke up with me and her replacement likewise reneged, I threw in the towel and asked Paul Major if he wanted to go. He consented, Neil Young sucked, and shortly after our return to the dorms, we grabbed a couple acoustic guitars and played all night. We even recorded some of the performance that consisted mostly of improvisation.

I often wonder what my life would have been if just one of those girls had gone to the Neil Young concert instead of Paul.

While this first night established the fact that Paul and I could “read” each other musically, hence play a song together that only one of us knew or create something on the spot, we did not become a working band the next day, the next month, or even the next year for a number of reasons. We were college students whose education took top priority, we had other distractions (i.e. girls), we had no money to spend on equipment, no one else would play with us, no one particularly liked us, there was no place to perform, and we needed to improve our musicianship, though, at this point, we could have easily outplayed the Ramones.

A song Paul wrote for his senior project in high school called “The Moldy Dogs Theme” inspired our name. He had performed the tune at an assembly along with another equally provocative tune. Paul brought “The Moldy Dogs Theme” with him to Webster and we had lots of fun with it. Our first vocalist, Robert, suggested the song become our namesake.

Some of our “shortcomings issues” were resolved due to the fact that Paul and I worked on student security. This meant we sat at a “post” or area designated a security risk (doorway/entrance) usually from 7:00 pm to 1:00am or even later on weekends. Most of the security guards would read, talk to friends, or party, but Paul and I would borrow a couple guitars from the rich girls (who owned Martins and Guilds) and play all night while on duty. Others would occasionally join us. I suppose you could say this was our first paid gig.

During this time we mostly played cover tunes: anything from the British Invasion, Velvet Underground, Lou Reed, Stooges, Bowie, Dylan, and various hits of yesteryear. We never played what the typical Webster students wanted to hear: Doobie Brothers, Steve Miller Band, REO Speedwagon, Grateful Dead, James Taylor, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and bluegrass. Most of the snobby Easterners thought us musical cretins which is strange since the Velvet Underground, Lou Reed and others came from New York City and the rest of our list of influences was considered incredibly hip for the time.

Since we were treated like children and considered musical dregs, we never could find the missing components of our group during our first two years. We did have a total of four “guest” lead vocalist. Each had strong points and, in some cases, not such strong points. Regardless, none were serious enough to invest time and/or money into a group.

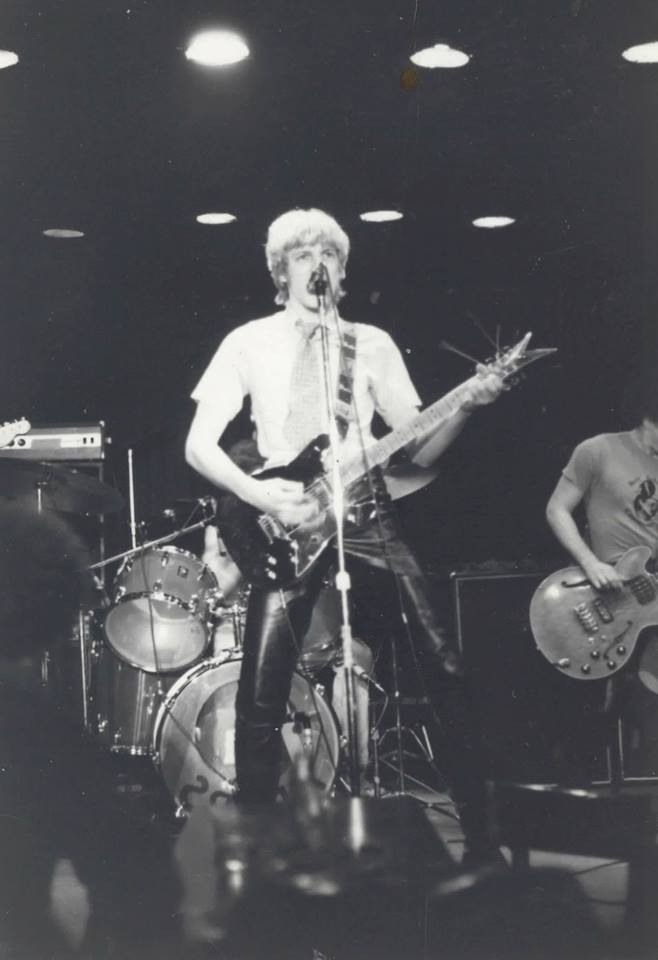

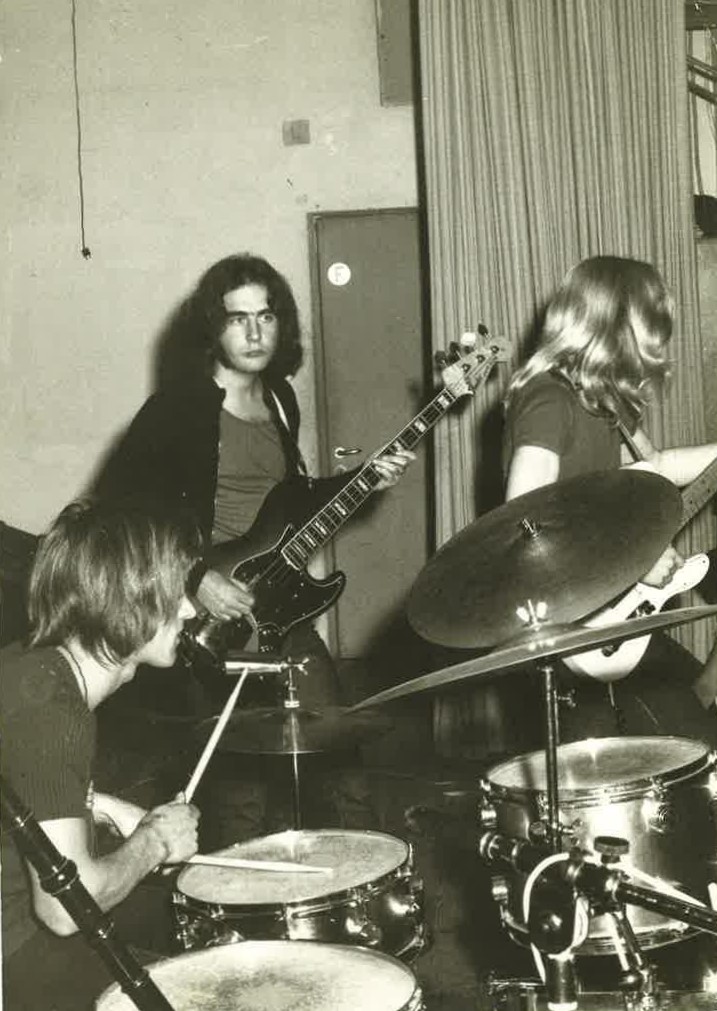

For the most part, Paul and I became synonymous with The Moldy Dogs. We snagged some pick up musicians for gigs, jams, or recording, but, in our early years, any attempt to find dedicated, permanent group members failed. Eventually, we played as a foursome, with Paul Wheeler-bass and Dave Lordi-drums, mostly during the summer of 1976 and summer of 1977.

The MDs’ progress was slow due to our surrounding musical environment, our immediate goals (graduating from college), and our monetary needs (tuition, food, rent, expensive girlfriends…). In fact, we always worked full-time day jobs during our tenure in bands—music never supported us and usually drained our resources.

Once I graduated and started teaching full-time (1974) I was able to devote more energy to the MD’s and scout for gigs, equipment, and group members. And by playing in public, we discovered the existence of a small, yet significant number of locals on our musical wavelength.

Do you remember the first song the band played? How was the band accepted by the audience?

We played a Little Richard song, “Slippin’ and Slidin’” and “Peggy Sue” by Buddy Holly on that very first night we jammed—so those may be the very first. Early jams at Webster would have included several Stones songs (“Parachute Woman”, “No Expectations”, “Get Off Of My Cloud”), and we filled many hours with Velvet Underground, and Bowie tunes.

As for originals, we composed “The Moldy Dog Theme”, “Jack The Ripper”, “Transient Situation”, “Personality Disorder”, “I’m A Gravedigger Honey”, “Madeleine”, “Fat Thigh Mary”, an early version of “Sat Chit Ananda” and a number of others.

As mentioned above, most of the students at Webster failed to appreciate our musical direction. Only the theatre students thought we were cool because we played a lot of glitter rock, especially Bowie, Reed, and T Rex.

Later, playing away from the college, in bars, restaurants, and clubs, was an entirely different story. Even our early lunchtime gigs before a few dozen elderly women went over well. I can’t explain it. Maybe they sensed that two young, relatively handsome creatures were trying to please them while they devoured their fruit cocktail and that was enough to make their afternoon. Who knows?

Our very first song at our very first official gig was The Kinks’ “Well Respected Man”. I truly believe we consistently performed quality material, never banging out the current Top 40 schlock that filled the airwaves. We chose classics from the past (this was well before radio stations played “oldies”) or we dug up obscure gems audiences would have never heard. We carefully added originals to our set lists and made sure the audience was on our side before we delved into provocative material. This was, after all, Midwest America.

What was the scene like in St. Louis?

What scene?

No real “scene” existed in St. Louis in the early to mid 1970s. The hot spots from the earlier decades were long gone.

There were a number of clubs where live music was performed by competent rock bands. Every band played Top 40 hits or tunes by popular or regional artists—exact replicas of the actual recordings. Occasionally a band might try an original song that usually sounded like the cover material they performed.

Pavlov’s Dog, and a few other local bands did achieve some notoriety around the St. Louis area though all fell short of igniting any real scene. They performed original material and, in some cases, scored major record contracts but, unfortunately, were soon dropped from their respective labels.

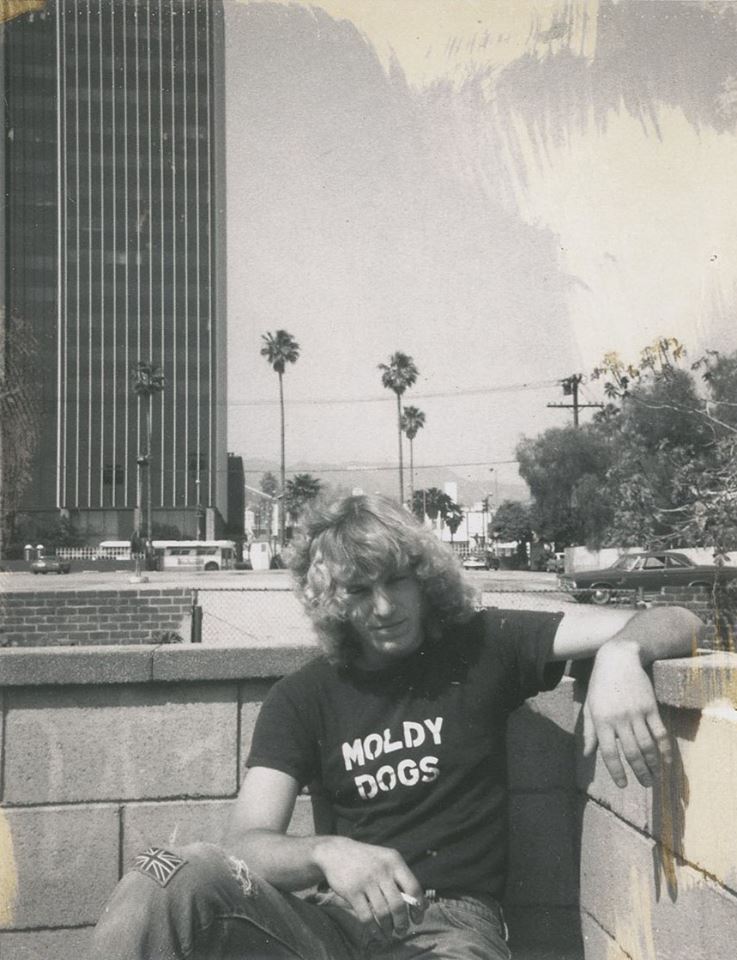

The MD’s and friends connected with others who shared our musical taste (1960s pop/rock/psych/glitter and what would eventually be termed “New Wave” or “punk”) and formed the nucleus of a scene that mostly centered in University City (St. Louis) and Washington University (KWUR radio).

We had some steady gigs that attracted followers, and we organized the Punk Out Party and the First St. Louis Punk Rock Festival, two early and well-attended events.

Undoubtedly, there were other musical cliques in and around St. Louis who were performing and writing in similar musical genres, but we were all unknown to each other. Before the age of the Internet, connecting with others was nearly impossible.

To give an example, The Moldy Dogs and The Dizeazoes, two early post-1970s “punk” bands, lived about one mile from each other in University City. Yet, each had no idea the other existed. Once the MD’s started playing out regularly in our neighborhood, we met.

What sort of venues did The Moldy Dogs play early on? Where were they located?

Mostly small bars, family style restaurants, sit down delis and the like—gigs no other band would consider due to the wages and the audience. The majority of our haunts were in the Central West End of St. Louis, University City and Webster Groves, which housed Focal Point, where the owners demanded we leave the premises because Paul played an “electrical guitar.”

In his articles on The MDs, Jack Partain rightfully claimed we “had an uncanny ability to understand our audience.” We had an enormous repertoire compiled via six nights of rehearsals a week, which was necessary when playing 4-5 hours at each gig (with only five minute breaks between each hour of playing). The Musician’s Union would have banned us from the planet had they known or cared about us.

We also performed our own arrangements of songs—never sounding like the recorded version and offered a variety of genres: Andrew Sisters to The Stooges. This also limited the venues. Though we broke many rules, perhaps part of the reason we succeeded was the fact we worked very hard to keep our audience entertained without being “in their face.” Many people came to enjoy dinner and chat. We gave them something of interest when they became bored with their dinner guests.

Of those places we performed, only Duff’s is still operating, though they no longer have live music. The Grove, The Joint, The Fourth and Pine, Lums, and other steak houses and bars vanished many years ago. Focal Point still exists, albeit at a different location. Probably waiting for the MDs to return so they can toss us out again because Paul still plays an “electrical guitar.”

While these gigs may sound inconsequential, they served a purpose. We developed into seasoned musicians/performers and we eventually attracted a small, but faithful tribe of like-minded classic, psych, pop, rock aficionados who started hanging out with us at KWUR radio on Friday nights when David Thomas broadcasted his “Rock-It” show. The St. Louis Punk Scene started here and we were one of the catalysts.

We also performed in Hollywood at a club on Highland Avenue and on the Venice beach. Likewise, in NYC, Paul and I were booked as The Imposters at all the clubs in the Village: The Back Fence, The Bitter End/Other End, Le Café Figaro, Folk City, Mills Tavern, Elbow Room, and others. Later, Gaslight, Tonic, Sidewalk, C-note and many other NYC venues would be added to this list.

How did you decide to use the name “The Moldy Dogs”?

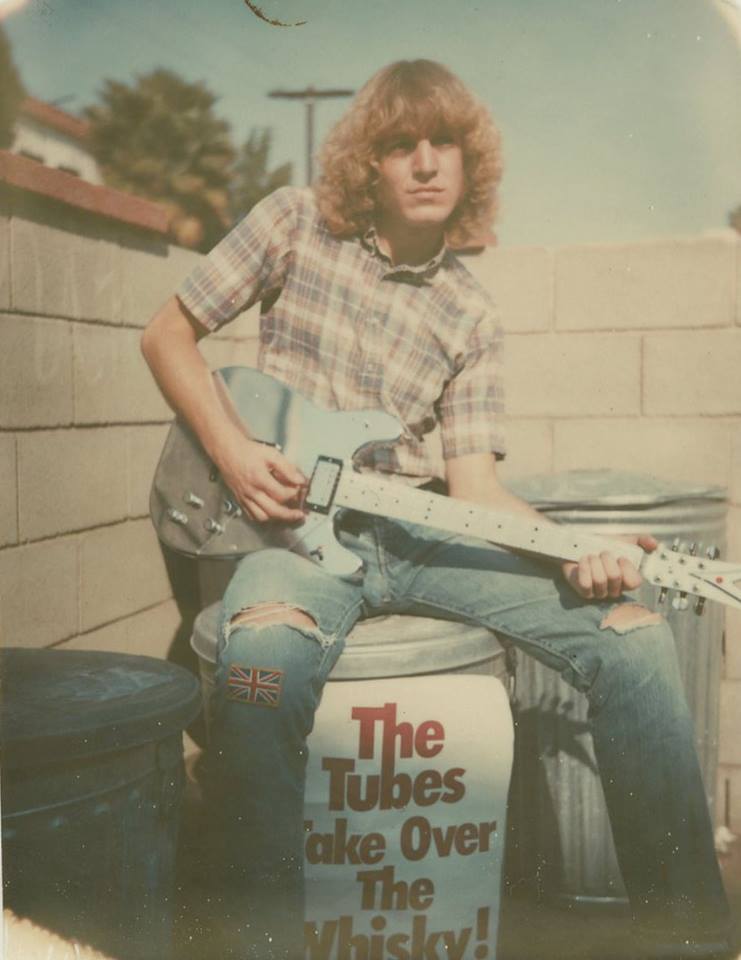

Though already covered in a previous question, The Moldy Dogs name was altered after our stay in Hollywood when our new songs, written under the influence of the California sun, became laden with pop/psych influences. We were probably getting tired of the “demented themes” present in most of the early MD’s tunes.

Paul wrote some amazing material in Hollywood. Every tune was fattened with remarkable, memorable pop hooks and left field lyrics. With this flood of new compositions and what many viewed as a departure from our pre-LA style, we wondered if the name The Moldy Dogs really personified our music.

So, upon our return to St. Louis, we started referring to ourselves as The Moldies. If you consult the KWUR “Dirty Thirty” (Top 30 charts in 1977), you’ll see us listed as The Moldies.

What influenced the band’s sound?

All the bands whose music we performed in our early gigs influenced the MDs, especially The Velvet Underground/Reed, Bowie, acid folk, and British Invasion. Psychedelic/left field artists undoubtedly intrigued Paul. By spending time with Jon Ashline and Bruce Cole, I was exposed to a variety of bands out of the mainstream: The Godz, Fugs, Bonzo Dog Band, David Peel and some krautrock.

Listening to our early practice tapes reveals an amazing assortment of blues rooted material, most likely influenced by our love of the Stones, especially their acoustic recordings. Truth is, we were playing to our strengths—Paul could dish out some ferocious as well as melodic blues licks and my rhythm technique, though simple, was strong and intense. Including blues in our set seemed to “legitimize” our performances to Midwest audiences.

Once we focused entirely on originals, our goal was to sound different than everyone else, which was not an easy task even in the early/mid 1970s. Our song subject matter had to be tastefully provocative and had a hefty spoonful of imagery and catchy hooks. To give an example of how far we took our pledge for originality, shortly after we wrote “House Of Buttermilk”, a friend informed us of Hoagy Charmichael’s tune “Oh Buttermilk Sky”. Of course, the two songs had nothing in common other than the word “buttermilk,” but that was enough for us to question our lack of originality. We decided to keep our song intact because the early lyric drafts never mentioned the word “buttermilk.” (Only the later recorded version added a different last verse that included the word.).

Our lack of resources (money, guitar gear, effects boxes, amplification) also inadvertently affected our sound. Those cover bands made big bucks and usually lived at home, thus affording them an arsenal of sonic toys and options. We were on our own from our college days and had little to spend on fancy gear. Hence, we simply could not sound like another band if we tried. Our delivery was unadulterated and pure, which both helped and hurt us. The feedback from the music business usually claimed: “great songs, competent musicians, need to work on your sound.”

How did Wolfgang and the Noble Oval came together?

Jon Ashline and I met in 1968 when we were both employed at the same Burger Chef restaurant in North St. Louis County. I had just turned 16 years old. Initially, Jon and I only socialized at work. Eventually we started hanging around his house in Ferguson, MO and producing what were called “break in” recordings.

These were early forms of what is now termed “sampling.” Dickie Goodman released a series of “break-in” records in the 1960s that became instant best sellers. They consisted of fictitious interviews of known or unknown people involved in hot topics of the day: UFO’s, student unrest and so forth. After an interviewer asked a question, the response would consist of a “snipped” line from a popular song. We created a number of these recordings on reel-to-reel tape, usually concerning our own local, personal world.

Not only were we experimenting with sound recording, as well as examining lyrics and the innuendo of their delivery, but also in searching for music samples, I plowed through Jon’s record collection. He followed many genres of rock music. I mostly listened to top ten hits. Suddenly, my exposure to offbeat music was greatly increased and, in addition, Jon introduced me to record collecting. Though we were still into the British Invasion, Jon turned me on to The Stooges, The Velvet Underground, The Bonzo Dog Band, The Godz, The MC 5, The Fugs, and The Mothers of Invention. Safe to say, that all these groups were out of the mainstream.

My dream of forming a rock’n’roll band occasionally surfaced. I literally begged Jon to actually create some music. He was very reluctant to waste time in an attempt to give the Beatles or Stones a run for the money when it was very apparent to the entire universe that we lacked any innate talent.

Nonetheless, with all these new, unconventional musical influences came a realization that we could find our own niche and sound too. After all, The Godz hardly sounded like The Beatles—and they were allowed to release albums. These off the wall groups greatly inspired us. We gave up trying to sound like virtuosos, which was obviously unattainable for us.

The real jump-start came when Jon’s little brother received a toy drum set for Christmas from K-Mart marketed as “The Noble Oval.” It was a tin, toy set, not a cheap set of adult drums. You could pick up the entire kit with one hand. Jon agreed to bring it over to my house so we could record. We now had a drummer. We now had a band.

Wolfgang and the Noble Oval was strictly angst captured on tape—we never played live. The first session was in my bedroom. We rocketed through ten songs that were, with a couple of exceptions, composed on the spot. We usually turned on the cassette recorder and just started playing. We rerecord a song or two because the first attempt was either a lost cause or the song seemed to have potential and a second attempt was deemed worthwhile. In this case, we may have scribbled down some of the better lyrics from our first recording, especially if we were going to sing together.

I played my Custom Kraft guitar and Jon pounded those “drums” while singing, and, simultaneously, spurting lyrics. He had natural rhythm and offered a solid, steady, driving beat though those skins hardly resonated any degree of tonality. Leam, In Your Face, Back on the Streets, and Long Time Leavin’ were standout tunes. Jon even attempted a drum solo in SOG Man (remember: toy set of drums). We considered rerecording the tune and just throwing the drums down my basement stairs. Maybe we should have. The session was entitled Live Oval Jam.

After a tough evening of taping, we got together with Bruce Cole and cruised around town. Bruce really got a kick out of the recordings and helped us decide which songs were keepers. He also named the group by calling us “Herr Wolfgang and the Noble Oval.” We would play the tapes for anyone foolish enough to listen. Most were shocked we had the nerve to perform such trash or take credit for the writing and playing.

The next recording session was particularly raunchy. The four letter words were really flying out of our mouths, probably because both Jon and I were having problems with females and we were loaded to the gills with anger, frustration, and Michelob. Of the thirteen songs produced that evening, there were only a few clunkers. The best were “Eva Braun, “Wolf and Oval Theme”, “Whoa Jonny Gimme That Beer”, “Why Not-Because”, and “She Was Innocent”. This session was entitled Sweet Sessions Of Silent Thought (yes, Willie Shakespeare was also an influence). Once again, our only fan, Bruce Cole, gave us the thumbs up. As before, we rounded up the usual suspects, subjected them to half a song or so, and received the usual rejection.

While other sessions and impromptu jams occasionally haunted our basements and bedrooms, Wolfgang and the Noble Oval eventually faded away. John’s participation was strictly for laughs—he never imagined the day when anyone would appreciate our recordings. We both grew musically though our aspirations became very different.

You moved to New York City and formed bands like The Tears, The Metros and Walkie Talkie and at the same time also started solo projects. Would you like to tell us about your days in New York City?

My musical life in New York City was the best of times and the worst of times. Though I struggled financially, lived in substandard conditions, saw the competition in the local music scene propagate at an alarming rate, and spent way too much time composing alone in my apartment, many stimulating experiences crept into my life. The East Village, West Village and even the Upper West Side, (with all its faults) were alive and kicking. Outside my front door was either an adventure or an observation that served as an inspiration for a new thought or idea for a song.

All this is worth mentioning so one can understand what my living circumstances offered. Some days, things were glowing and flowing, while other days I sat alone, dejected and broke, even down to my last quarter. There were times when I felt blessed and fortunate to possess a wealth of skills and opportunity, and yet futile stretches when even others concurred I was cursed and destined to be a miserable flop.

I suspect nearly all involved in the NYC scene between 1975 and 1982 have differing views and experiences due to age, goals, success, and memories. For the young, NYC offered the perfect environment to express oneself, become a local celebrity of sorts, experience the camaraderie of fellow band members, and to live in a perpetual state of arrested development.

Keep in mind that by the time I moved to NYC (Fall 1977) I was twenty-five years old, a college grad with teaching experience, had been around since the beatnik and hippy eras, and had lived through disco (let’s face it punksters, disco was a pretty easy act to follow). I had already revolted against my parent’s generation, discovered new priorities, values, and morals, accepted alternative lifestyles, and would be considered “counterculture” by the majority of Americans. I also had been playing in bands since 1970, all of whom would be classed as out of the mainstream, ranging from very crude grunge to power pop. So, what I’m getting at is the fact that primitive rocknroll, subversion, alienated youth, revolution, and all the above were nothing new for me. I was not seeing the punk movement through the eyes of a sixteen year old, and, though I know this is a very unhip thing to admit, I was not reckless with my life or others.

I loved punk/New Wave for recapturing the spirit, simplicity, energy, and power of rock’n’roll. This was our only chance to drive a musical nail into the coffin of the pretentious drivel that surfaced in the progressive music movement, the overproduced, sterile groups who topped the charts, the nondescript artists signed by the major record labels, those conceited musical geniuses who bored me to death with their endless solos, and all the banal 1970s pop and disco that polluted my environment. I performed music that would never fit in with the horseshit coming out of my radio. I wasn’t making a political statement, didn’t need the symbols that proved I was a punk, didn’t need to look like I crawled out of the gutter, or desired a mohawk, tattoos or piercings. But I always had a thing for leather.

Looking back, I now understand my lack of success in the punk rock scene. While this revelation hardly requires a social scientist to comprehend and, as a concept, was something I had grasped since my earliest days in rock’n’roll, it took Sam Shepard’s play Cowboy Mouth to drive the point home. Like most popular movements, the punks were seeking gods made in their image. As a hero who encompassed their attitudes, dress, look, musical tastes, age, preferences, and general behavior, I fell miserably short of being the idol they sought. Never mind I appreciated and was exposed to raw rock’n’roll from the beginning of the genre and participated in the like since the early 1970s. And it was hardly relevant that I too despised all the garbage the entertainment business peddled to the masses.

While the initial punk apostles (pre-1975) were, to a degree, frustrated musicians, innovators, and bereaved rock’n’rollers, the ensuing disciples that flocked to the scene, at least those visible on the street, ripened into a loosely united army of misfits, complete with regalia, that substituted attitude for art. I simply could not represent nor be empathetic with many of the punk rockers’ mentalities—or even fake it. I sought acceptance into a wider sphere of popular music culture and imagined my input and output would change the face of modern music.

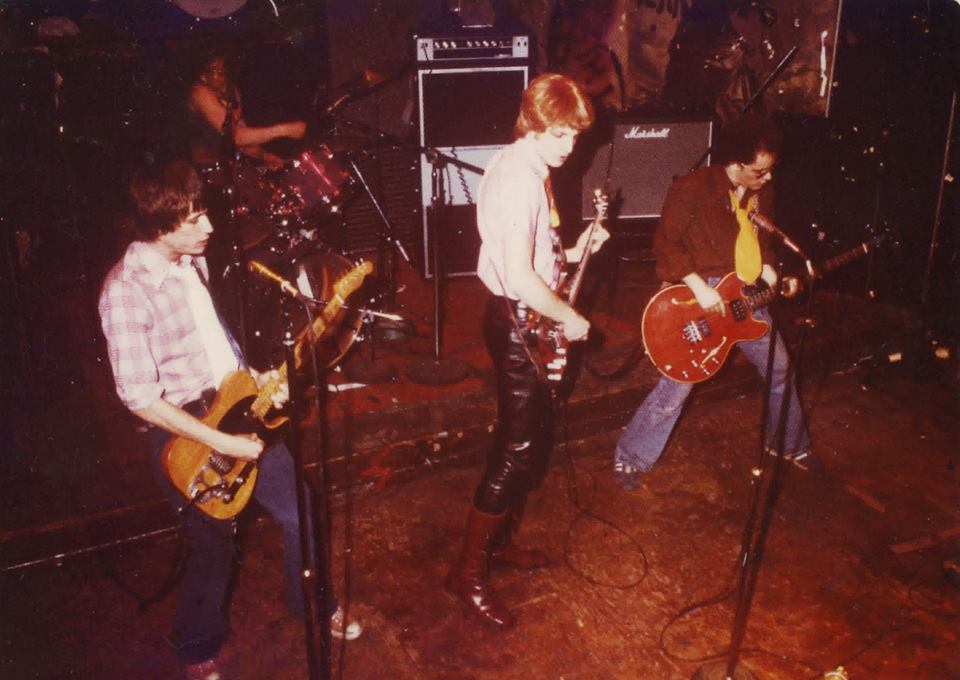

Anyway, going back to the beginning—Paul Major and I arrived in the West Village (Bleecker and McDougal) when The Tears were in full swing. We had just spent a few months hibernating in Far Hills, NJ in a house where we had access to a rehearsal room. With Pee Wee Mathiesen (bass) and a twelve-year-old drummer, Ralph Grasso, we decided to throw together a band playing mostly old Moldy Dogs’ material. Since the songs were simple, the band became tight overnight and we played CBGB’s in the middle of the Blizzard of 1978.

Shortly after our second gig, we were signed to a management contract. We never had a tour, a recording date, interview, publicity, or lunches with record company big wigs, but we played every club regularly.

The Tears also helped launch Club 57 and a few other venues that became important to the scene for many years. We booked all the early shows at Club 57 and owner, Stanley Strychacki, became my most trusted friend. We were always treated like royalty at Club 57 and allowed to perform any time we wished. Later, when the Stanley relocated to Irving Plaza, I became his stage manager.

The Tears could have morphed into a Cheap Trick style band had we stayed together. Every time we played, our performance and sound improved exponentially. Likewise, Paul Major and I had many power pop tunes sitting around our apartment gathering dust. Truth was, we all had other musical passions and rehearsal/travel was difficult to arrange with a very under age drummer who lived in the middle of New Jersey.

We played many gigs with former NY Doll Arthur Kane (The Corpse Grinders) due to being represented by the same management company. I shall always cherish the time I spent with Arthur. He was such a tragic figure—a sensitive, sweet human being snared by a brutal business.

Shortly after The Tears stopped flowing in the early summer of 1978, Pee Wee Mathiesen and I discussed forming a power pop/root rock band influenced by The Beatles, Buddy Holly, and the Who. Our timing seemed perfect because Beatlemania was a solid hit on Broadway, The Buddy Holly Story still fresh in the movie theatres, and The Kids Are Alright had reignited the popularity of The Who.

We initially shared a rehearsal space in Little Italy with Jerry Nolan and Walter Lure of the Heartbreakers and Sid Vicious. We ran into them every so often when coming/going. Sid never managed more than a growl when we conversed with him.

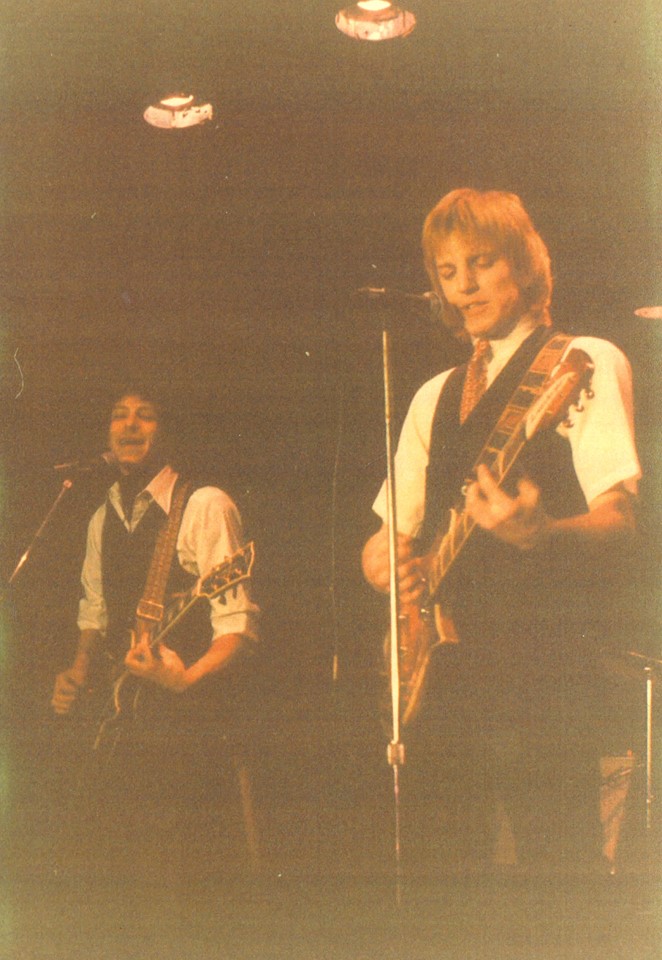

The Metros began as a trio (with drummer Sandy Klein), but we soon added Andy Marvel on lead guitar. Andy was an amazing guitarist. With his membership in The Metros, I could relax on stage. Instead of practicing lead guitar all day, my focus became songwriting. In October 1978 I somehow managed to write eight new songs for our set list. Things quickly fell together for the band and our management, left over from The Tears, helped book our gigs. We were moving up the food chain, getting top billing or booked with more interesting feature acts, and improved steadily by assembling a stronger set of unique tunes.

The recording session a little over a month later is covered in the “insights to recording sessions” question. We were excited about Punk is Dead and believed we had a hit that would launch the group a few rungs up the ladder, but the punk audiences completely misunderstood the song. We were also shocked by two events; Andy left the group to return to college and Variety Magazine skunked a performance at Max’s Kansas City, with our new lead guitarist (David Newman) who was an exceptional pop rock musician.

Without a record release and our forward momentum slowed due to the down time in replacing Andy, the group lost their way. We continue to play through the winter of 1979, though frustrations mounted for everyone. At this point, I should have taken the reigns and led the group out of the doldrums. Truth was, my new TEAC 3440 4-track offered many productive alternatives to playing live and getting nowhere. The band was buried alive.

The Metros were a tight, dynamic rock’n’roll band. I’m sure we had our detractors and the “art rockers” probably found us trite. We were not experimental, repetitive, obnoxious, political, or abusive to our audiences. Our direction was along the lines of Rockpile, The Move, The Stones, and a touch of The Who, and we came pretty close to achieving the sound we desired.

In addition, we also sought to find originality while staying within the genre of rock’n’roll, and that was challenging considering the vast number of groups now entering the scene as the 1970s was coming to a close. By this time, the scene was open to many different trends and I do believe The Metros, though not entirely unique, were still hard to define. And, though I hate to brag, we had some solid original material.

For nearly the entire tenure in The Metros, I was living on the Upper West Side in Manhattan with my manager. This was a convenient situation for both of us—when she worked overtime at a major publisher, I babysat and helped her child with homework. Her apartment served as a place to store my recording and performing equipment. Once free of The Metros, my strategy was to write and record songs for successful performers. With my new multi-track recorder and some time on my hands, I assembled dozens of demo tapes of decent quality which, occasionally were sent to established artists.

When bored, I might audition for a group or, for a short while, fill in on guitar or bass for a session. I joined The Sorcerers briefly while they searched for a permanent bassist. The experience was exhilarating because these guys were pretty rowdy. This offered some variety to my otherwise tranquil life since leaving the downtown scene.

In the late winter Paul Major and I commenced a project (The Rain Sessions) in order to write and record some new material for a potential band. We never completed one song. Since I had my TEAC and a fresh reel of tape, we decided to record some of our older material and to lay some tracks on songs that needed finishing. This project led to the sporadic recording of dozens of songs over the next eighteen months.

In the late spring, David Leeds (former NY Brats bassist) and I started discussing the possibilities of forming a band. David already had a long history in music and The Brats (named by Alice Cooper) were one of the earliest post 1970s bands that bordered on punk/glam.

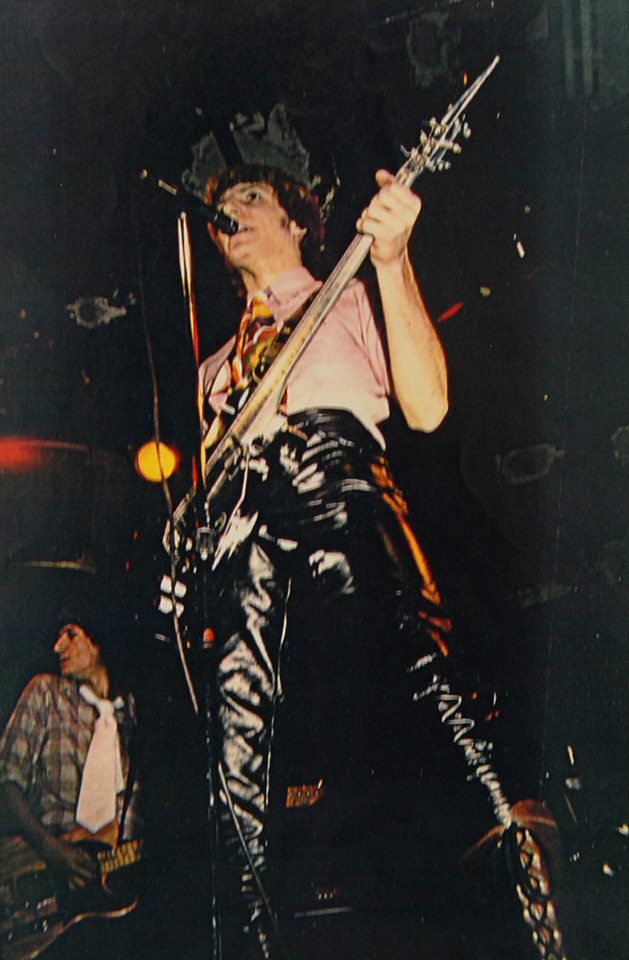

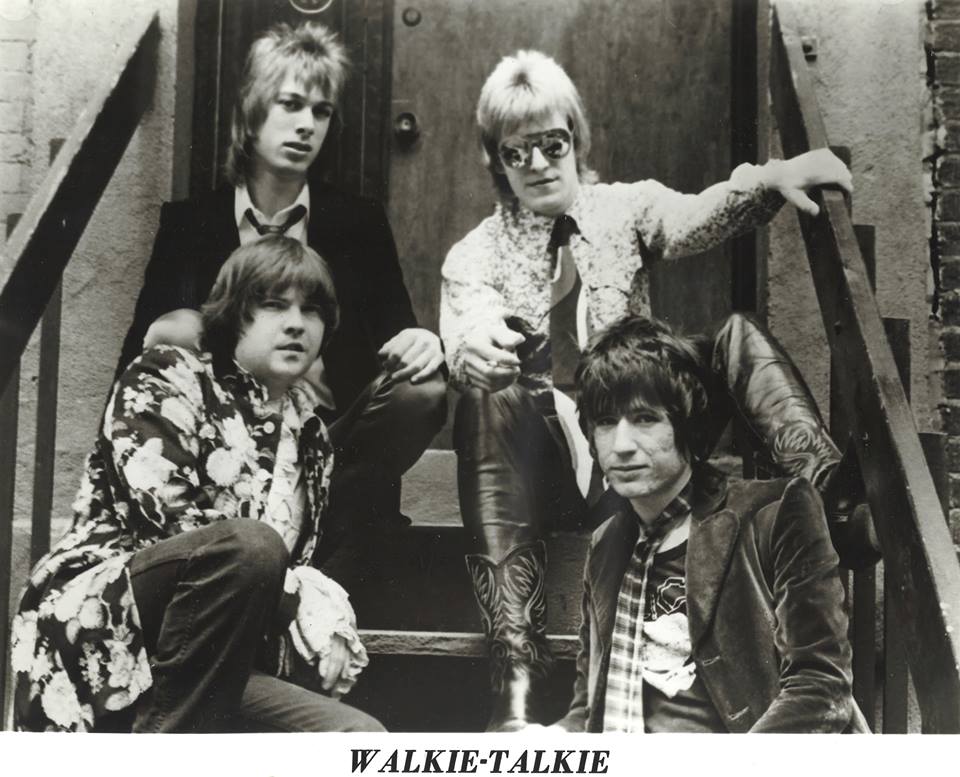

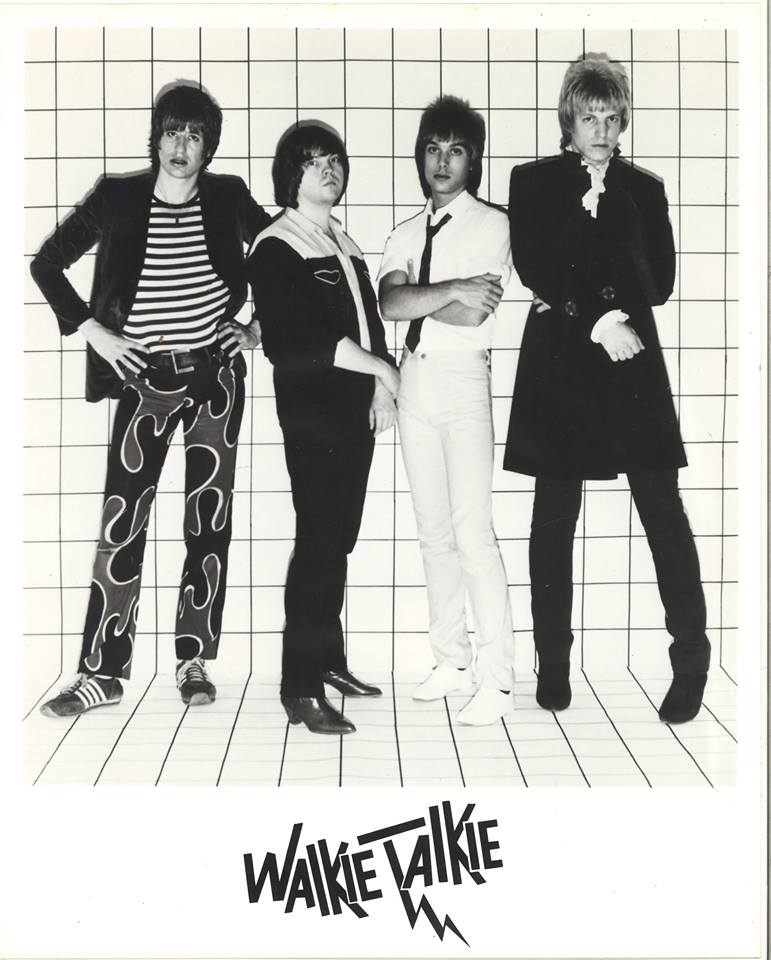

The process, which included my moving to the East Village, took nearly a year, but after countless advertisements, auditions, frustrations, and wasted dollars, we whipped up Walkie Talkie. Randy Zweiban joined on drums and, upon realizing NYC had few lead guitarists that offered the whole package, we talked Paul Major in enlisting. Our search for a lead vocalist proved fruitless, and I begrudgingly agreed to rise to the task.

WT was my dream job—WARP (Write and Arrange songs, Rehearse, and Play live). Never had to manage the group, collect and pay bills, deal with club owners, record execs, print shops or swim with any sharks. Plus the rest of the band was very professional in dealing with all the problems.

We also spared no expense in WT. We had roadies, light men, sound men, and lucked out with free recording time, photos, parties and you name it. I had just moved to the East Village and in spite of the hardships, once the group was ready to roll, I became resurrected to fight one more battle.

WT never gave a bad performance and seemed to move forward for most of our tenure. We played outside Manhattan—Queens, Long Island clubs (My Father’s Place, Malibu) and some new, some old venues in the city—Zappa’s, Camouflage, Gildersleeves, Youthanasia and others.

My songwriting at this time was peaking due to the bands’ expectations—WT simply would not accept new material that was inferior to that already in the set. Paul, Vic Harrison and I owned a cache of untested, original tunes, but we were all cognizant that every new addition, regardless of composition quality, must gel performance-wise and fit our image. So I recorded my new compositions on the multi-track, carefully arranging all the parts. Playing the band a polished version of the prospective song helped insure its acceptance. However, WT gave every song a workout before approval.

We also lucked out and received free studio time at Counterpoint, a state of the art recording studio in midtown Manhattan. This enabled the band to professionally record four songs to serve as demo tapes and, eventually, our single released in 1981.

Walkie Talkie also achieved notoriety for refusing to accept Madonna as a lead singer prospect. Nothing against her—we were just filled up in the vocals department.

Though we were progressing, the group began to slightly splinter over music direction and other problems that caused some strained situations. But even more so, personal frustrations were mounting. Vic and I suddenly lost our day jobs, which further complicated our lives. For my part, I was tired of being broke and devoting endless hours to music only to watch others succeed with seemingly less effort and abilities. I was also ready for something new, and with the issues and roadblocks, my brain became overloaded.

This may very well have been a temporary situation or state of mind. We should have just taken a month off, then regrouped. But when Randy announced he was leaving to join the Secrets with whom WT shared their rehearsal space, we were floored. Vic and I were not thrilled about the prospect of searching for a new drummer, though David was willing. So the group folded. Ironically, our single Standing Over You/Something Called Love that had been released months before was now receiving great reviews.

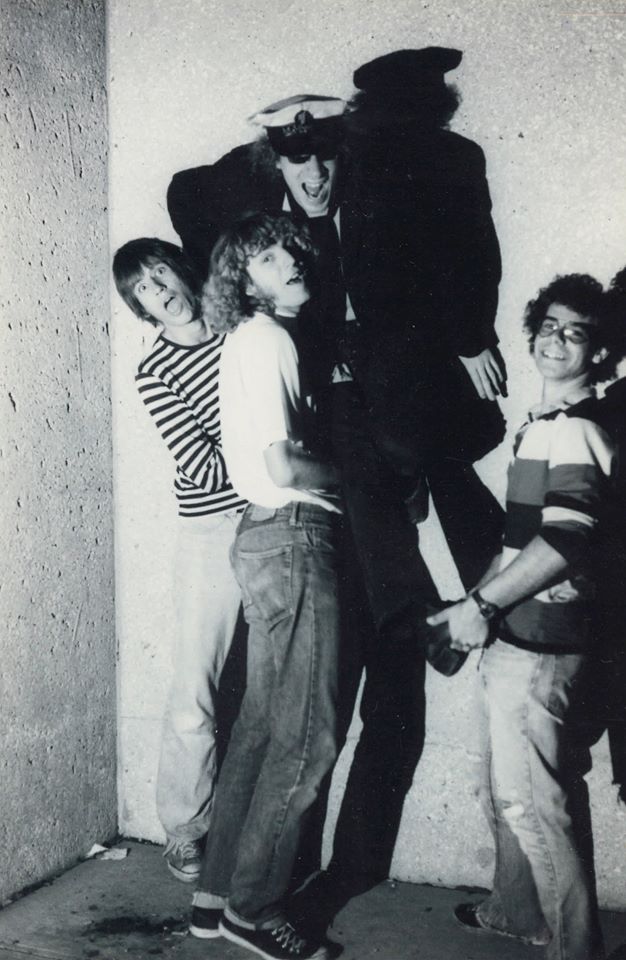

Though Walkie Talkie, with Paul or Vic, was a hard-working group, we filled every minute together with non-stop hilarity. Individually, we may not have been great comedians. Together we were able to play off each other in a way that created as much humor as music. After a night of rehearsing, my voice was shot and my stomach ached—not from singing and playing, but from laughing. This is perhaps the only time period of my life that I totally regret letting slip away.

Immediately after WT split, I began work on the Reflections From The House of Buttermilk compilation—approximately eighty recorded originals mixed to four cassette tapes. Vic Harrison assisted by offering his lead guitar skills, as did Steve Rowe who had played keyboards on a couple tracks in The Counterpoint Sessions. The bulk of this work is known as The East Village Sessions. Most of the rhythm tracks were recorded in the Music Building, our rehearsal space in the Hells’ Kitchen area of Manhattan. All the guitar, vocal and keyboard tracks were finished in my East Village apartment. I had very tolerant neighbors. Bless them.

The post-Walkie Talkie period consisted of many projects from commercial jingles to presenting my songs for other artists’ consideration. I had connected with Robert Gordon shortly after The Metros breakup and he showed an interest in I Shouldn’t Talk to You. Robert reconnected after my move to the East Village and requested more material. At this point, he was such a hot commodity that every songwriter in the Western Hemisphere was hoping to score some grooves on his next album.

Since my first days striving to become successful in the music business, we always discussed what happens when one hits that milestone: your 30th birthday. Very few rockers are signed to record or management contracts once they reach this plateau, unless they are a known entity. In July 1982, my three-decade milestone came and, on that day, I had an appointment with a MAJOR RECORD LABEL.

David Leeds had prewarned me that the person who set up this interview had ulterior motives. David (remember—a hair stylist) had the gift of gab, and could milk a confession out of anyone. And, being dedicated to me, he passed on the lurid truth. So when I noticed that the A&R man who was interviewing me and listening to my tapes was a little removed from the process, it came as no surprise.

As it turns out, the reason the interview was scheduled had nothing to do with hit songs, careers, or me. I would love to tell you why I was sitting in that schmuck’s office, praying he would like my recordings or, at least, the compositions, but, truthfully, even if I had topped The Beatles, it wouldn’t have made any difference.

At that point, I hung up my guitar.

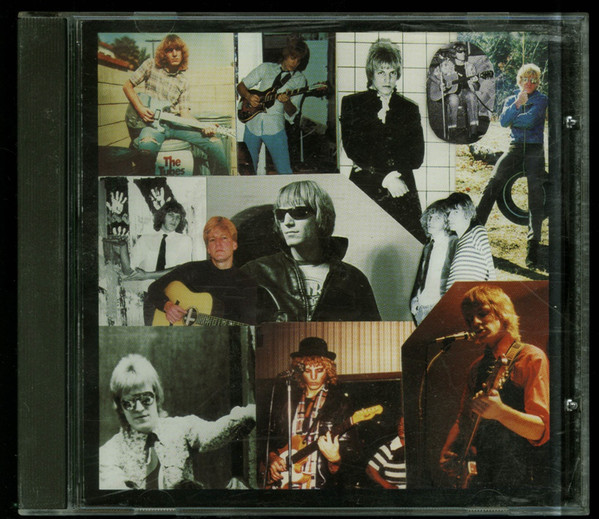

What can you tell us about the latest release: Reflections From the House of Buttermilk?

As mentioned, Reflections From The House of Buttermilk was conceived in late 1981 when I decided to catalog all my songs immortalized on tape. The project also entailed finishing existing recordings in various states, and included a batch of potential tunes currently living only on paper.

Around eighty songs were mixed and mastered to four cassettes. Those tapes lived together in a boxed set for nearly thirty-five years.

By late 2014, many of my original tapes and even later CDs, were deteriorating. I decided to update RFTHOB and professionally re-master my favorite recordings onto four CD’s. Carl Rowatti of Trutone Mastering (Nanuet, NY) was chosen for his expertise and equipment that included analog decks necessary for my reel-to-reel and cassette tapes.

The big question was how to catalog the recordings onto the CDs. I decided the majority of the nearly three hundred recorded songs fell into four or five genres: power pop/rock, acid folk, pure pop (lighter pop), comedy, old country/rockabilly, and avant-garde/experimental. The first three categories had the most candidates.

Songs were chosen based on the quality of the recording, performance, and uniqueness. Unfortunately, time had destroyed some of the original masters so we resorted to using scrap and reject mixes, which Carl resuscitated through a combination of talent and technology.

When the four volumes are completed, all my bands will be represented with at least one entry. The songwriting is mine except Volume II (acid folk) that features The Moldy Dogs and thus a few tunes written by both Paul Major and me.

The new RFTHOB was launched with a fifteen song CD in 11/2014 and planned for release after Christmas. Problem was, my memoir was finished by late January and the decision was made to include the CD with the book. After initial publication interests failed to materialize, we returned to a CD release over a year later. Meanwhile, the vinyl craze was upon us. Well, we eventually decided to go analog. Carl and I cut three tunes off the planned CD and re-mastered for vinyl. The three songs we cut left us with a record tightly packed with power pop/rocknroll.

The project would still be a daydream had not David Edge, a designer from Williamstown MA, entered the picture. He not only designed and assembled the package, but he also provided the enthusiasm and determination to complete the project when I was ready to surrender.

Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

The songs are best discussed by dividing them by the various recording sessions. These comments are based on the original liner notes that were dropped from the album due to lack of space.

The Rain Sessions Spring 1979/Fall 1980

After playing in bands together since 1972, Paul Major and I formed our own groups in the summer of 1978. Less than a year later, at the urging of friends, we began working again in a series of songwriting sessions that would hopefully serve as a foundation for a new group/project.

We met at my manager’s apartment. With fresh ears and a desire to learn audio engineering, I worked constantly on the basic tracks of dozens of my new songs and a few by Paul. Eventually, all they needed was lead guitar—so, when we were being unproductive as co-writers, we just laid the finishing tracks on several of our individual tunes. When Paul joined Walkie Talkie, his lead guitar tracks once again provided the finishing touches.

The Rain Sessions were so titled as an inside joke because the new group names we brainstormed apparently all had something to do with rain: The Rainmen, Umbrella, The Puddles, and various psychedelic imagery dealing with weather.

St. Susan of State Recorded April 1979

Written in 12/76, this song spoofs the girls who attended Missouri State colleges. I was teaching in St. Louis and working with some new college grads, some whom I drove to work.

Hearing them every day, first thing in the morning, left me over-exposed to their personal drama, lifestyle, goals, female problems, and so forth. I was only a couple years older than these new teachers, but their mindset, hang ups, and focus seemed so different when compared to the girls I had known in college. I was experiencing the dawn of the “me” generation.

The song sounds Kinkish, especially since my natural vocal delivery resembled Ray Davies. My “falling” bass line was supposed to resemble a continuous laughing–ha ha ha….

Wolf Roxon: vocals/guitar/bass Paul Major: lead guitar David Crigger: drums

Produced and engineered by Wolf Roxon

Arabian Night Recorded 10/24/80

Written in 78/79 in an attempt to compose a song full of launched, loaded, ringing chords that would bury groups like The Clash. Unfortunately, this 4-track demo, recorded by Walkie Talkie over a year later, needed a little more production to compete with any major band.

We were taping a batch of songs to determine our best material for future recording dates in real studios. So we set up my TEAC in our rehearsal space at The Music Building and spent an entire weekend (Fri-Mon) recording non-stop. We only completed the rhythm section (bass, drums, and a scratch rhythm guitar). The vocal and lead and rhythm guitar were added later in my apartment.

Paul played this lead that still knocks me out—the way he takes off and closes his lead fits the song perfectly. We improvised the middle section and the bridge lyrics, and always planned to add more. The arrangement is skeletal, but, in a way, the sparseness fits the song which is about never getting anywhere.”

Wolf Roxon: vocals/guitar Paul Major: lead guitar David Leeds: bass

Randy Zweiban: drums

Produced and engineered by Wolf Roxon

The Somerville Sessions Fall 1978

By the fall of 1978, The Metros were playing the rock’n’roll clubs in NYC and were the house band at Club 57 on St. Mark’s Place. Well-rehearsed, well-managed and well-received, our tight rock foursome was ready for the next step—a record.

Pee Wee Mathiesen (bass) had attended audio school with Lenny Grasso (his 12 year old brother, Ralph, played drums in the short-lived, but very busy group, The Tears). Grasso owned an 8-track studio in Somerville, NJ, so the Metros booked a session. Lenny’s studio was brand new—the cement was still wet in places. All his equipment, including the 8-track Ampex w/ 1” tape was fresh out of the box.

The session should have been cancelled. I had the flu–worst case of my life. I laid my guitar tracks then crawled into an empty box the corner of the studio and shook and chattered. When it came time for the vocal track, they pulled me out of the box, propped me in front of the mic, and let the tapes roll. I could barely breath when recording I Shouldn’t Talk to You. If you listen to the vocal track without the instruments, the wheezing and gasping for air is very pronounced. Who knows, I could have started an entirely new trend in vocal delivery.

Andy worked hard on his leads. Still, the rest of the band questioned his style of using harmonized motifs found in contemporary mainstream and southern rock for our songs, that conversely targeting a root rock audience. Compromise prevailed.

Punk is Dead Recorded 11/78

Written 7/78 during a lull in the NYC scene, the song appeared a send off for punk rock. But with Sid Vicious’ demise later that fall and his death a few months after, all the Metros viewed the lyrics as taking on an entirely new dimension –an anthem that would be appreciated by punk audiences. They missed the point.

Achieving maximum power pop was the main goal. The first time I played through the song for the band at drummer Sandy’s house in Brooklyn, his entire family and some neighbors ran into the basement ecstatically claiming the band now had a hit. Oh, if the music business was that easy.

A combination of Lenny’s new Ampex 8-track and the bands’ predictable tight performance under any conditions resulted in some strong basic tracks.

Wolf Roxon: vocals/guitar Andy Marvel: b.v./lead guitar

Pee Wee Mathiesen: bass Sandy Klein: drums

Produced by Pee Wee Mathiesen

Engineer and assisted by Lenny Grasso

I Shouldn’t Talk to You 11/78

Composed 10/78 during a very productive month when we basically revamped our entire set. This tailor-made tune was a turning point for The Metros and, along with Andy’s arrival, stoked our live performances.

This song was a straightforward rocker in the rockabilly vein very similar to Rockpile and Dave Edmunds. Mathiesen has accurately described The Metros as “a complex combination of power pop, rockabilly, blues, and psychedelic. We loved the music of The Kinks, Stones, Beatles, The Move, and The Who, but we never copied anybody.”

Written after an outlandishly wild loft party in the West Village. A woman, clothed only in high heels and an open blouse, cornered me for a discussion on current events. Her gang of suitors grew rather anxious over our conversation. Yours truly managed to escape gracefully and live to write three songs about the experience. Inspiration often arises from the strangest situations.

Wolf Roxon: vocals/guitar Andy Marvel: b.v./lead guitar

Pee Wee Mathiesen: bass Sandy Klein: drums

Produced by Pee Wee Mathiesen

Engineer and assisted by Lenny Grasso

The Counterpoint Sessions 7/80 and 10/80

David Leeds was a valuable and resourceful member of Walkie Talkie not only for his musicianship, positive attitude, and charming personality, but also his connections. As a hair stylist, Leeds had several clients in the music trade. Enter John Allan-Gifford, not only a client of Leeds, but also an engineer/producer at Counterpoint Studios, a modern state of the art 24-track recording studio in Midtown.

John’s recording experience was primarily with jazz groups. Somehow, David convinced him to branch out to power pop/rock and, of course, mentioned Walkie Talkie as pop/rock group willing to experiment with a jazz producer.

Although recording engineers barely received a livable wage, they were given comp time, that is, free studio time to record/produce their own music projects. This was a huge perk, given the fact that a couple songs could easily rack up $20,000 in studio costs.

Counterpoint Studios was a recording heaven for someone used to working on a 4-track TEAC without mixing boards, noise reduction, quality EQ, clean power amps, and special effects. Of course, since the sessions were free of charge, the hours available were usually odd times when the studio was not booked. The sessions began in mid summer 1980.

Standing Over You Recorded 7/80

WT had devoted a few weeks to analyzing all of their songs in order to determine which would work best with a producer who had very little experience in rock’n’roll. One night, at rehearsal, during a break, I started pumping out the chorus (hook) to Standing Over You. The music and lyrics just spilled out of me. The band liked the phrasing and within a day, I finished the lyrics and arrangement. Catchy, new, fresh, and relatively easy to play well, the band chose the tune for the upcoming sessions.

In addition to the WT members, the band called on Mitch Weingart for some synthesizer parts to add dimension to each song. I had written the middle lead for Standing Over You on guitar. When Mitch played the same notes on the synth, the song’s sonic territory fit perfectly into the early 80’s sound. Halfway through the lead, Major’s guitar takes over and offers a snappy ending.

The song itself is quirky and lyrically quite disturbing, concerning a young, inarticulate boy who has trouble communicating his love to an ungrateful female. Every approach he tries fails, so he just runs over her in his pickup truck (bizarre by early 80s standards, unfortunately, quite a common modus operandi today). Literally no one, including some members of the group, realized what events were unfolding in the lyrics. Again, this trait of “more going on in the song than the listener is aware” is rooted in my early influences.

The song was written in the upper registers of my vocal range—why the key wasn’t changed is a mystery. When I failed to hit the highest notes, Gifford simply slowed the tape speed, which, in turn, lowers the pitch, so I could reach the highest notes. However, on playback at normal speed the recorded vocal sounds Chipmunkish. When the 45 single was mastered, the speed was increased again, so now the vocals sounded like a castrato.

Unfortunately, the best mix of Standing Over You deteriorated over the years and only the reject mixes survived.

Wolf Roxon: vocals/guitar Paul Major: lead guitar/b.v. David Leeds: bass/b.v.

Randy Zweiban: drums Mitch Weingart: synth/keys

Produced and engineered by John Allan-Gifford

Sooner or Later Recorded 7/80

Written in 2/79 and was originally recorded in the Rain Sessions with Paul Major on lead. Shortly after composing this song, I considered it a throwaway and filed it in my logbooks. Upon realizing the arrangement matched some standard drum tracks I had on a tape, we quickly recorded a version.

The song always received a great reception live and became WT’s favorite number. For the Counterpoint Sessions, it was chosen without hesitation. As sometimes happens, the songs one thinks are going to be blockbusters, fail in the studio. The newly recorded version of Sooner or Later was considered a bit weak and was not even chosen for the B-side of the WT single.

I must accept full blame for having Mitch play the “whoopee rises” on the synth. I wanted a rising note on the synth at the end of each line in the chorus. The sound in my head was lost in translation when trying to recreate it on keyboard. It wasn’t Mitch’s fault—just a bad idea of mine that should have been dropped. Paul had some amazing fills on the original recording made during the Rain Sessions—we should have stuck with those. Surprisingly, many listeners like the whoopee rises. I can live with that.

Wolf Roxon: vocal/guitar Paul Major: lead guitar/b.v. David Leeds: bass/b.v.

Randy Zweiban: drums Mitch Weingart: synth/keys

Produced and Engineered by John Allan-Gifford

Something Called Love Recorded 10/80

Written in 9/80 with the original demo recording immediately presented to the group for consideration for the upcoming second sessions at Counterpoint (along with Rennie).

While on the surface this song appears to be a simple rocker, the timing, due to a “riff” that occasionally intercedes like a soliloquy in a play, catches the listener off guard. The Bowie influence (Low) in the interludes and the Garson type ending (Aladdin Sane) are very slight, but just enough to make the song defy categorization.

The original ending fade was at least 90 seconds long. The entire group sang the pitches of a chromatic scale while Steve Rowe (piano) added an avant garde/atonal feel ala Mike Garson. When we finished and heard the rough mix, everyone was speechless—it sounded amazing. Well, the ending was cut severely and the final mix, though good, was not what we heard in the studio. After the record was pressed, the original tapes were erased and reused by the studio.”

The Aquarian, a local New Jersey weekly, called Something Called Love:

“…a classic…there’s just enough pseudo psychedelic vocalizing and back to basic instrumentation to elevate this tune to the local Garage Band Hall of Fame.”

Wolf Roxon: vocals/guitar Vic Harrison: vocals/lead guitar

David Leeds: vocals/bass Randy Zweiban: vocals/drums/xylophone

Steve Rowe: vocals/piano

Produced and engineered by John Allan-Gifford

The East Village Sessions 2/82

After the Walkie Talkie breakup, I decided to finish recording nearly a dozen songs from the Music Building Sessions as well as tunes that were not WT material. As mentioned, Vic Harrison graciously offered to provide lead guitar (if I would provide snacks and desserts) and Steve Rowe and Jim Maresca volunteered their talents on keyboards (with no snacks or desserts).

All the sessions were recorded in my East Village apartment (except the drum tracks).

Sat Chit Ananda Recorded 2/82

Originally written in 9/74 (with a 1976 rewrite) and played extensively by The Moldy Dogs (as a duo) and The Tears (NYC-1977-78), this song was a primitive barnburner. I dropped the middle bridge for this recording. Harrison delivered a scorching lead and Rowe provided the psych keys. I discovered, well after the recording session, that we forgot to add the last lead guitar track. To fill the space, I merely copied Harrison’s middle lead, then again to another tape deck, flipped the tape backwards, and sent the signal back to the original recording, (one lead forward, the same lead backwards) giving the effect that all hell is breaking loose.

Of all my material, this tune went over best with the NYC punks.

Wolf Roxon: vocal/guitar Vic Harrison: lead guitar Steve Rowe: keyboard David Crigger: drums

Produced and engineered by Wolf Roxon

Faded Recorded 2/82

Written in 11/78 with Genya Ravan in mind, who was breaking as a major artist. My manager knew Genya, so why not write a song for her next LP? The song was written, but the meeting with Genya never happened. The lyrics were rewritten, then filed away.

After Walkie Talkie split and the Reflections compilation commenced, I enlisted a drum machine and began filling tapes with the basic tracks for many songs, Faded among them.

Once again Harrison contributes a biting “Stones-ish” lead and Rowe plays piano on a Fun Machine—a mass market, cheap electric piano owned by my girlfriend (who eventually would become my wife for life—though we both divorced the Fun Machine).

Hating the sound of the drums, I later added a real snare, which gave the percussion less mechanical sound.

Wolf Roxon: vocals/guitar/snare Vic Harrison: lead guitar Steve Rowe: piano [mechanical drums]

Produced and engineered by Wolf Roxon

Only Heads Will Roll Recorded 2/82

Written 3/81, the origins of this recording are a mystery. These tracks are not on any of the tapes that WT recorded during their Music Building sessions. Most likely, the basic tracks (drums and bass) were recorded during a practice session since WT played the song live and the mystery drums and bass sound like Zweiban and Leeds.

I added my guitar and vocals and Harrison once again came through with a polished lead. The song would not have been new to him—it was a WT staple.

Lyrically very similar to Arabian Night with psych imagery involving lack of control over one’s fate, absence of benevolent power, and a hint of fear in unknown destinations. Traveling was one of my most severe phobias.

Wolf Roxon: vocals/guitar Vic Harrison: lead guitar David Leads: bass

Randy Zweiban: drums

Produced and engineered by Wolf Roxon

Can’t Call You Mine Recorded 2/82

Written 6/76 and 10/80. This song was partially composed (a few lines) when the Moldy Dogs were following the Rolling Stones tour in Louisville. The tune was finished over four years later in the East Village, NYC. Recorded at least three times, this song is one of my personal favorites and was performed both by Walkie Talkie and in my solo act in every live performance since its conception.

As in many of my songs from this era, you will find schoolhouse imagery, addictive yet hopeless love, and the surrounding environment mocking fate. The “clouds turn to rust” was something I saw when driving around Louisville the day of the Stones show. The overcast clouds were a brown, rust–like color, probably from industrial pollution is the Midwest.

Again, this is a leftover tape from the Music Building recording projects that initially only had Zweiban’s recorded drum track. I added the bass that seems to walk and dance around the forward pacing, slightly arpeggiated, steady, rhythm guitar, very different from the other recorded and live versions. Vic Harrison delivers a fitting ominous guitar lead.

Wolf Roxon: vocals/guitar/bass Vic Harrison: lead guitar Randy Zweiban: drums

Produced and engineered by Wolf Roxon

The Shaftsbury Sessions 1998-2013

The sessions at my home in Vermont began with the reuniting of The Moldy Dogs in 1997 and sporadically continued until mid-2000. (I recorded alone after 2000). While the MD’s reunion was relatively brief (less that a year of playing live in NYC) I was intensely focused and dedicated –often devoted 40 to 50 hours a week–that resulted in the recording of dozens of new and old songs. The Moldy Dog catalog alone doubled in less than a year when Major visited two or three times to add his lead tracks.

Recorded on a digital Roland VS-880 (8-track).

Eye for an Eye Recorded 3/2003

Written on 1/10/2000, most likely in NYC, the song was never performed live though the MD’s were playing out at the time. The song was finally recorded three years later.

Eye for an Eye would have fit perfectly into a Metros set. Harkening back the Rockpile influences, it’s a simple rocker with a vocal/drum-accented hook along the lines of Elvis Presley’s Hard-Headed Woman. The lyrics fly by very quickly, so several plays are required to understand the predicament of the storyteller who always thinks he is going to “even up the score,” but meanwhile the same strategy is being attempted by everyone else who enters his life. The bad “karma” results in life always coming after him.

Wolf Roxon: vocals/guitars/bass/drums

Produced and engineered by Wolf Roxon

There will be more releases coming out soon…

The original plan was a four volume CD set released at the rate of one per year for four years. Switching to vinyl was a financial disaster with total costs around $30 per LP, not including advertising. So we are considering releasing Volume II on double CD that includes Volume I. The same will most likely happen with Volumes III and IV.

Currently, as we speak, The Moldy Dogs have some record company interests for a record release that, if it happens, could change Volume II considerably. I plan on starting on the mastering process for Volume II this September—so any interested parties have to make a commitment pretty soon.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

The musicians with whom I had the privilege to perform and record were 1st class individuals and would rate from very competent to highly skilled on their respective instruments. Our lead guitarists were top-notched players. All band members were responsible and refrained from any destructive behavior such as hard drugs or excessive alcohol.

Each band, every period, had highlights.

Wolfgang And The Noble Oval: Pure fun. We were just having a good time with rock’n’roll with no aspirations or illusions. We could have cared less if anyone liked us. In retrospect, some lyrics are remarkable considering most were recorded on the spot with no rehearsal.

The Moldy Dogs: By far the most original, creative band. We began like W&NO and became highly sophisticated through a tremendous amount of effort and commitment. Our performance at The Mayfest (Webster Groves 1975) and the Punk Out Party (St. Louis 1976) were the highlights of our career though the Café La Figaro show (NYC 1978) and Tonic (NYC-2000) are noteworthy. I am most proud of the fact the Moldies cannot be categorized, still sound fresh, and were many years ahead of their time.

The Tears: Though the band was thrown together in order to play the NYC punk scene, we sounded raging, risky, and dynamic. Ralph was the most astounding twelve-year-old drummer anywhere, any time. Don’t let the punk press fool you—he was the youngest and most talented percussionist in the scene. Greatest gig was our last club date at Rockbottom. We let it all hang out and the ceiling collapsed on us. What a way to end it all.

The Metros: A solid band performing unpretentious rock’n’roll with American roots and British flavor. We never apologized to the punks for sounding professional or to the professionals for sounding punk. Our first time at Max’s Kansas City (1978) was perhaps the best performance of my life.

Walkie Talkie: Hardworking band that enjoyed every minute together. With all members, the band came first. Part glam, part pop, edgy, modern 1980s sound with a foot firmly planted in the 1960s. Clearly the best vocals of any group in my portfolio. Our performance at Youthanasia with the Bay City Rollers (when the Rollers cancelled at the last minute) was our best. We played our hearts out—not one ticket holder requested a refund.

My favorite songs are mostly the ones that literally wrote themselves—they just sprung from of my head. Only two are on this Reflections Vol. I LP–Standing Over You and Can’t Call You Mine. Others that may appear in the Reflections series or are on my CD released in 2000 (Legend Of The Lost): Marshmellow Zoo, Sweet Amagetone, I’d Like To Do Everything More, Then I Will Leave You Alone, and, finally two written with Paul Major: Rabbit Man and Baby Bones in the Basement.

So, there is a lot of unreleased material?

Yep.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

Most of my favorite LPs of all time were commercial offerings and have since become classics: Odessey and Oracle (Zombies), Village Green Preservation Society (Kinks), Beggar’s Banquet (Stones), Rise/Fall of Ziggy Stardust (Bowie), Fun House and Raw Power (Stooges), The Doors [1st LP], and Slider (T Rex). These are flawless albums.

Others that receive my highest praise:

Horses by Patti Smith Group, Gorilla by Bonzo Dog Band, Morgen by Steve Morgen, Pet Sounds by Beach Boys, Greatest Living Englishman by Martin Newell, The Way I Play by Bill Evans, So What by Miles Davis, Go Girl Crazy by The Dictators, Mustard by Roy Wood, Get It by Dave Edmunds, Essence by Lucinda Williams, Something/Anything by Todd Rundgen, Loaded by The Velvet Underground, Time Out by Dave Brubeck, Transatlantic Sessions by John Renbourn, Rubber Soul by The Beatles, Brilliant Corners by Thelonius Monk, Plastic Ono Band 1st LP, Imposters of Life’s Magazine by The Idle Race, She’s the One (soundtrack) by Tom Petty, Transformer by Lou Reed, I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight by Richard/Linda Thompson, The Liverpool Scene: Adrian Henry, Roger McGough, etc., every LP from Hunky Dory to Heroes by David Bowie, and, of course, both 45’s by Celia and the Mutations.

For the last twenty-five years I have mostly listened to music written before 1900 (Middle Ages, Renaissance, Baroque, Classical and Romantic) plus 20th Century Modern, and jazz. I truly believe Michael Brown (The Left Banke) was correct when he claimed if you only listen to rock’n’roll music, you may not get a very big dimension of possibilities.

Occasionally I will drop a classic psyche LP on the turntable, or something Paul Major suggests, or his compilation releases. Recently, a local record hound in Vermont passed away and his entire collection was dispersed in our area. I managed to snag a couple boxes of British acid folk, mostly CD’s, and some vinyl. Still listening to those.

As for current power pop/rock, I tune in regularly to KDHX (St. Louis), especially Rich Reese. His Pop! Beat! The Bubble Burst show is chocked full of gems from both past and current artists. Rich is incapable of spinning a bad record—finds everything out there worth a listen. All the KDHX programs are archived—so you never miss one.

Likewise, Andrew Sandoval’s Come To The Sunshine podcasts are filled with both familiar and very rare nuggets from the past. His shows are also archived and, between his shows and KDHX, I get my pop/rock fix.

Last word is yours.

I assembled some impressive bands with talented musicians who had likeable personalities. All folded too early. While every member had equal say in decisions and management of these bands, me being a founder, vocalist, songwriter, guitarist, and front person required additional leadership and responsibilities. I should have done more to keep my bands together and convince all to carry on. When enthusiasm waned, I too abandoned hope, perhaps believing change brought progress. Sometimes it did, but starting over wasted too much time. One day I opened my eyes and discovered I was too old for the scene. I regret this lack of leadership and tenacity.

I appreciate It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine and Klemen for providing the opportunity to discuss my past in the music scene. Of course, there is much more to tell and often interviews and articles touch only the highlights. Truth is, we lived every day for many years pursuing this dream. Seeking success in music occupied nearly all my time—my last thought at night and first upon awakening. In other words, an obsession. There is comfort knowing many thousands of others shared this passion and accepted the consequences.

And, as did so many others, I moved on with life: left New York, raised a family, returned to teaching, bought a bookstore, and became a librarian. Yet, there was always something missing. In the late 1990s I returned to playing, writing and performing music with a newfound enthusiasm. Within a very short time, my musicianship and writing skills seemed enormously enhanced over my past accomplishments and my new recordings restored the excitement and anticipation of my early years. Returning to New York, reuniting the Moldy Dogs, touring with Peter, Paul and Mary (as a tour manager) and playing the NYC clubs threw me right back into the fire.

Unfortunately, rock’n’roll is a young person’s game. Unless you are a well-entrenched celebrity with a glorious past, attempting progress at an older age is a futile gesture at best. However, like all other first generation rockers, we need to keep creating no matter what the roadblocks or failure rate.

Truth is, time will be the great equalizer. Decades from now, music archaeologists, in an effort to examine the past, will discover our music. The criteria, perception, evaluation and analysis they afford in this totally different musical environment may result in recognition for many of us who surrendered during our lifetimes. The current press darlings of today, without their multiple publicity agents, will be flushed down the toilet of time. After all, they are not producing anything noteworthy.

This prediction may seem a pipedream. Not only has this resurrecting process existed for years, but the study of music history demonstrates time and again the fate of composers and musicians last far beyond the grave. Bach, unknown in his day, has been considered one of the top composers of all time for well over a hundred years. Many of those very popular during their productive period, are long forgotten.

So, we must never stop creating music and developing our artistry. There is hope for an afterlife of recognition and fame, even if we are not here to enjoy it. Nothing beats the immortality one achieves by writing timeless music.

– Klemen Breznikar

Really enjoyed reading the interview with Wolf Roxon. I knew him as a youngster and as an accomplished musician. I have listened to his new album (vinyl) many times and appreciate the time and energy it took to get it "out there" for all to hear. Thanks to your magazine for publishing a very interesting storyline about his various bands.

Really nice interview, one of the best. I especially liked the last comment, so truthful and truly wonderful. Roxon's a fun and interesting man and he provides an entertaining and informative narrative on that great musical era. Nice photos too.

Very interesting, insightful interview. As a music lover of all genres, I really enjoyed the peek into the various music scenes. I really appreciate the artist's continued dedication to their passion. And yes, whether or not you have huge commercial success or just the personal success in honing your craft, the music lives on forever, influencing others lives and bringing joy.

This is an interesting history of a very versatile musician. I also knew Wolf when we were both (much) younger, and this gives an excellent timeline of his career so far. Looking forward to hearing much more from him in the near future when the rest of "Reflections From The House Of Buttermilk" is released. Thanks for the music and the memories Wolf!

The life of a musician is not as easy at it looks! Getting gigs and making money is difficult in the best of situations. This article goes to show you that having that passion and stamina and loving what you do can last a lifetime, even if you have to get "real" jobs in between to support yourself and a family. Not many continue loving this art as long as others, but I think it would be safe to say that Wolf put his all and then some into making great songs and music. Best of luck in the future and never lose that passion!

Whoa yow… I didn't even remember some of this stuff until reading it now… kudos Wolf & Klemen for such an in depth and thorough telling of things… those were magic times and seem even more so now in 2018! In fact so much info is in there I took two days to find time to read it all!!

thank you

I have had the Joy and Pleasure of Knowing Wolf since the days of Webster College. St. Louis was a stronghold for a Vibrant Music Scene in the early 1970's. Many national recording acts were brought here in the 1960's – 70's because the feeling was, "If it plays in St. Louis, a band could go national. There has been an interest in the early days and of the wonderful radio station we have that started playing "Psychedelic Music" KSHE. Music is Love