Catapilla interview with Robert Calvert

Robert Calvert is a founding member of progressive rock band Catapilla. He played on both of their albums, 1971’s eponymous ‘Catapilla’ and 1972’s ‘Changes’.

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music?

Robert Calvert: I was born in Chilwell, Nottinghamshire, England in 1944. My first involvement in music came when I was ten years old, I joined the church choir associated with the small preparatory school I attended in Attenborough. This ended in 1955 when my family emigrated to Melbourne, Australia.

Neither of my parents were musical, but they did buy an old piano from a family friend which my older brother began to play and have regular lessons. When my mother offered the same for me I declined, I was simply not interested in the light classical pieces my brother was being taught or the manner of his tuition.

The music that first inspired me was early Rock ‘n’ Roll, from artists like Little Richard, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis, then later it was traditional New Orleans jazz, which had a revival in the late 1950s to the early 1960s. In fact it was this ‘Trad’ boom which was the driving force in my desire to play an instrument.

When did you begin playing music? What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

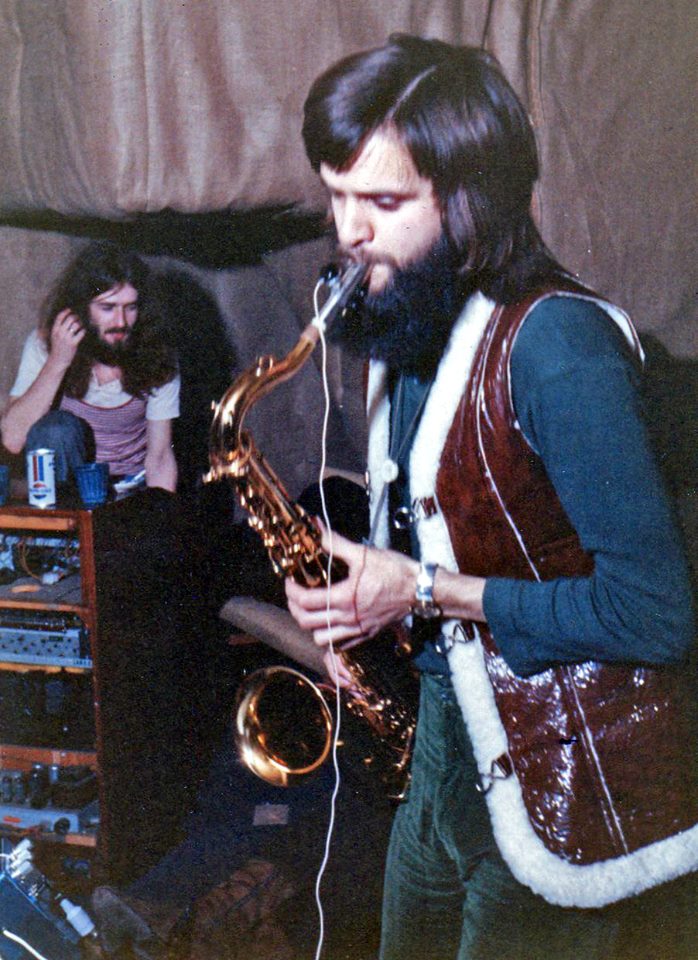

I come from a working class family and my parents, both of whom had no secondary education, believed that four years of secondary education was enough for my brother and myself. Consequently I began my working life at the age of fifteen as an office boy in a Melbourne city advertising agency. As I walked around the city of Melbourne doing my office boy errands I would stop and peer into the windows of second hand musical instrument and pawnbroker shops and be infatuated by the band instruments on display, especially trumpets. In the tradition of working class self improvement I began night school classes for a diploma of advertising. One evening, soon after I started my course, a fellow student brought an old C.G. Conn tenor saxophone into the class, an instrument he wanted to sell. Previously I had had a go on a friend’s trumpet and found it rather difficult to even get a sound out of, so the allure of the trumpet was fading. When my fellow student opened the case of his saxophone, not only the look of the instrument captured my attention, I even remember the smell that emanated from the case. The old C.G. Conn tenor became my first instrument, this was March 1960 when I was fifteen, nearly sixteen. At this time the music I mainly listened to and the local bands I went to see were Traditional Jazz bands.

What bands were you with prior to the formation of Catapilla?

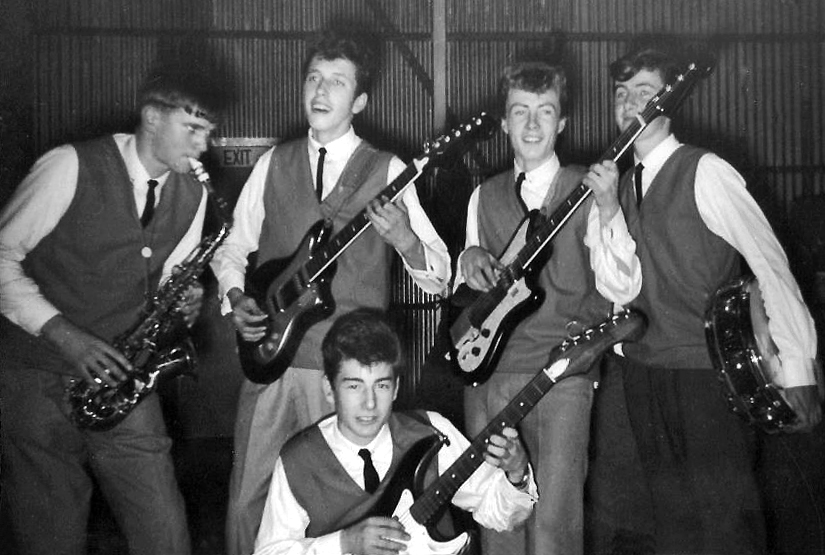

The youth movements of this period broke down into two groups – Jazzers and Rockers, I was definitely a Jazzer. I’d been taking private lessons for about nine months when I was seen with my saxophone case on a Melbourne railway station platform by some ex school mates. They had a Rock ‘n’ Roll covers band. They invited me to have a jam with them, following which they asked me to join them. I was sixteen and the band’s name was ‘The Lincolns’.

I enjoyed the collective playing so much that I abandoned my desire to play Trad Jazz and joined the ‘Rockers’ youth sub-culture! In Melbourne I played in about five or six local bands between 1961 and 1966, all of them Rock/Pop covers bands, before sailing back to Britain in December 1966.

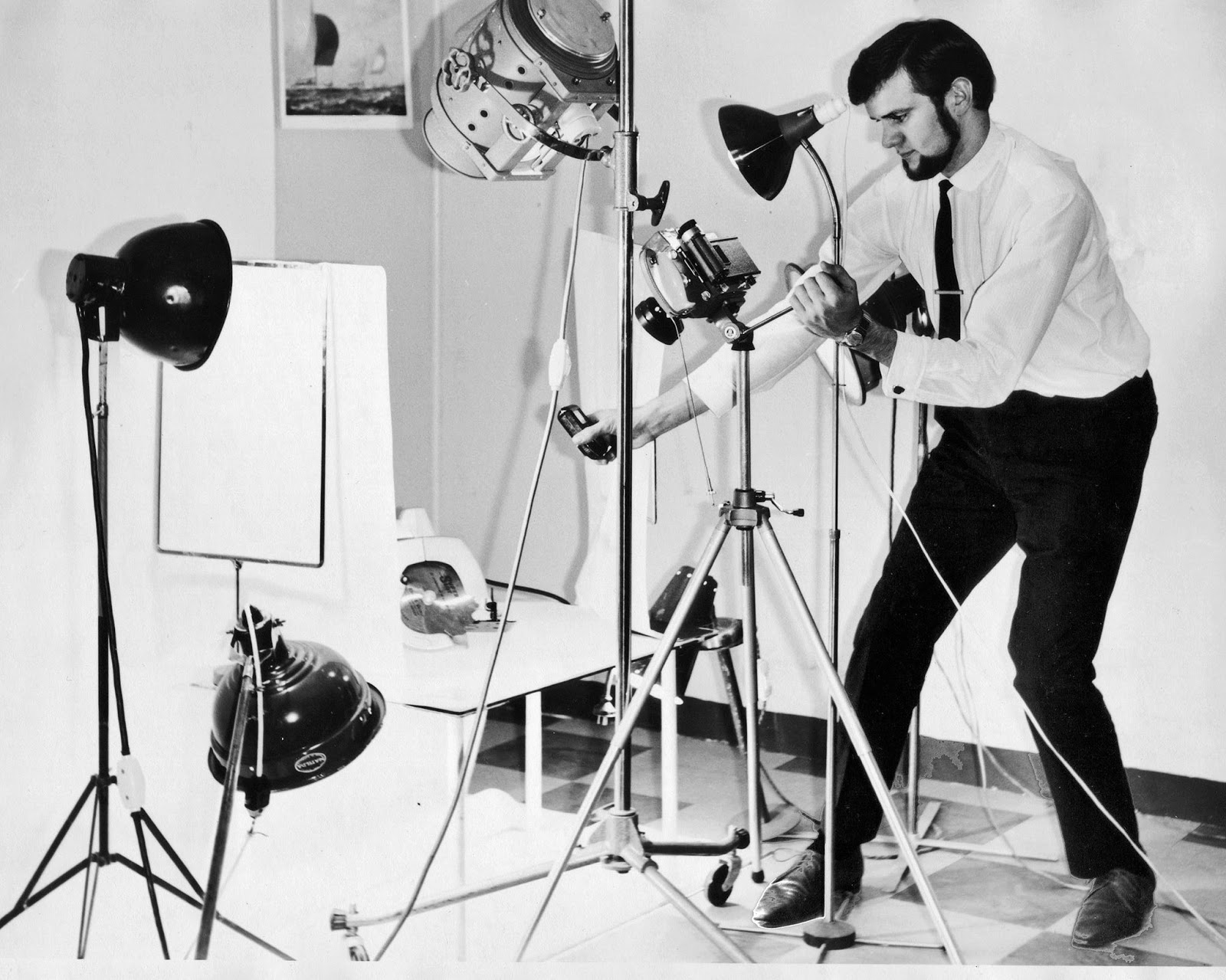

My profession at that point was photography, I’d had a really good job in Melbourne running a studio for a large hardware retail chain, but due to my inability to gain a job equivalent to the one I’d left behind my interest in the London music scene took over from my interest in photography.

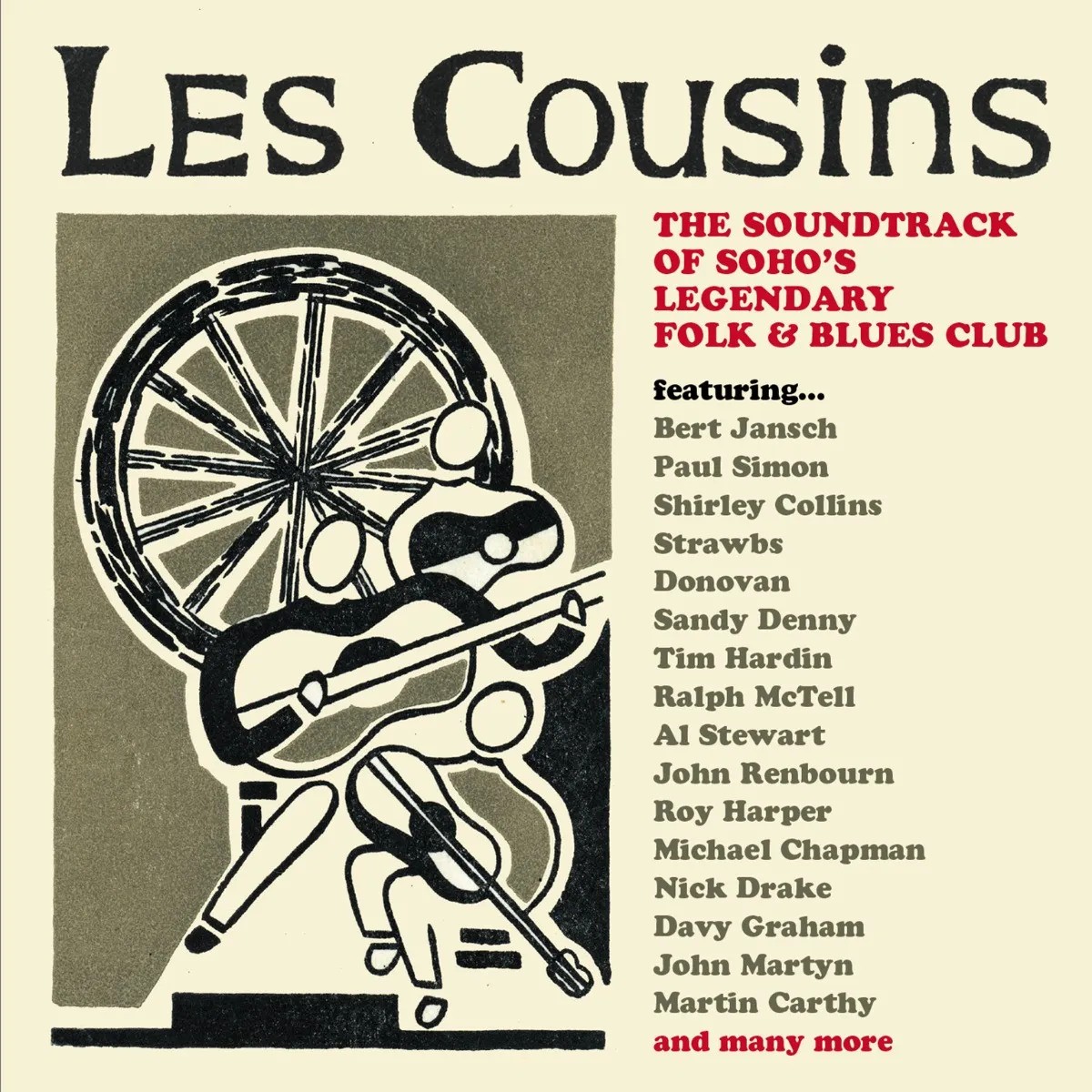

Following an advert I placed in the Melody Maker in the latter half of 1967 I auditioned with a South East London Chicago style blues band and got the gig. The band was ‘Thackary’, we were taken on by a really good agent who got us some fabulous support gigs in London’s premiere venues. We shared bills with Joe Cocker’s Grease Band, Steve Winwood’s Traffic, Ike and Tina Turner Review, Rory Gallagher’s Taste, Fairport Convention and more. I would have loved Thackary to have had a crack at turning professional but most of the members had good day jobs that they weren’t willing to give up. After a year with Thackary I left and went searching for more professionally minded musicians. I met and jammed with Brice Porteous (Savoy Brown) a couple of times, it was great fun but nothing eventuated.

Can you elaborate on the formation of the band?

In April, 1969 I answered an ad in the Melody Maker and went to the Arts Lab in Drury Lane London, to audition for a new band being set up by drummer Louis LaRose. For me it was a successful audition but during the months following this the personnel changed almost weekly, until after less than a year Louis himself left! The remaining musicians and I decided to carry on. I knew an excellent drummer, Malcolm Frith, who was playing in a big band style rehearsal band, I asked him to join us and he did. The guitarist we had at that time was Barry Clark, who left us and was replaced by Graham Wilson, who had been playing on American bases across Europe and had just returned to London. Jo Meek was the singer in this first band. At a gig we played at (if my memory serves me correctly) the Revolution Club in central London Tom Paxton heard us.

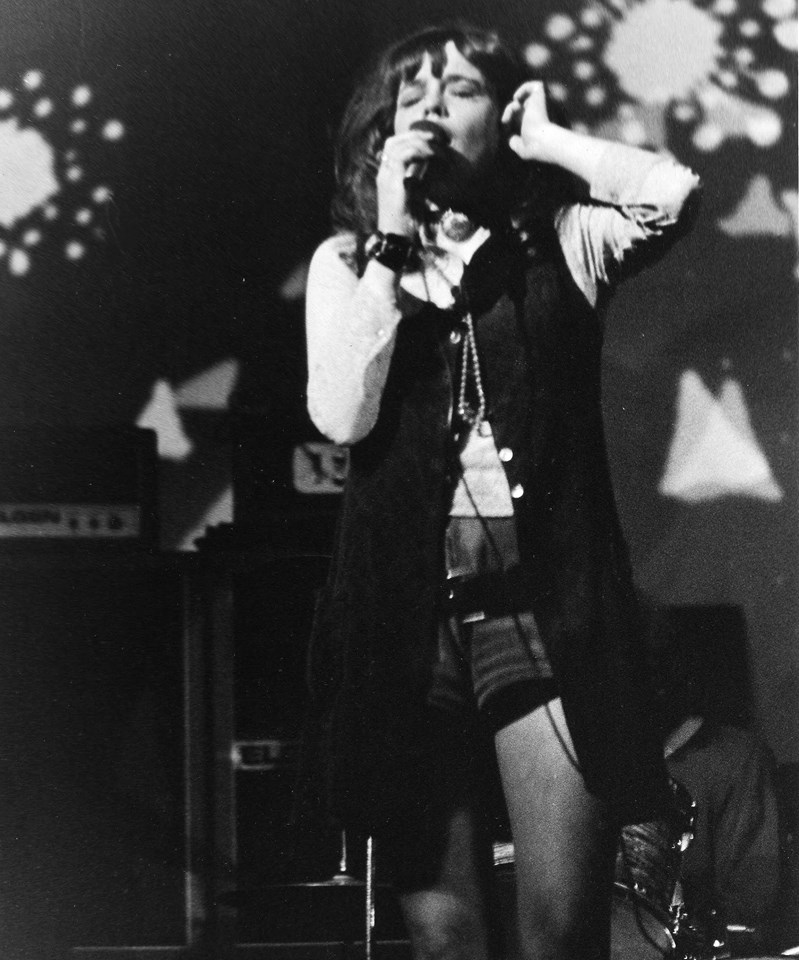

Jo’s boyfriend felt our band was not suitable for Jo’s singing style and probably in a conversation with Tom this was confirmed because very soon after this she left the band. We advertised for a replacement singer and Anna Meek, Jo’s sister got the gig. These are her own words describing this event “I took over as singer with Catapilla when my sister vacated this same working space. I did not know until the audition that this was so.” Anna’s move into the band established the personnel who went on to record the first self titled album.

When and where did Catapilla play their first gig? Do you remember the first song the band played? How was the band accepted by the audience? What sort of venues did Catapilla play early on? Where were they located?

Whilst miraculously I have through the course of a long and somewhat disrupted life managed to retain a few items, like some written records and short notes from my time with Catapilla, I did not begin keeping a diary until 1974. I can only remember the songs we played on the albums. I mean, since those days I’ve played in dozens of bands, consequently I have learned and forgotten whole repertoires and am still today quite active with a number of bands, whose repertoires I have to keep practicing in order to stay on top of my game. Some general recollections about gigs was that as soon as we came under the wing of the Orange Agency we had regular gigs in a number of London’s night clubs, The Pheasantry Club in Chelsea, Blaises Club in South Kensington, Revolution Club in central London, plus a few College and University gigs in London and the provinces. The bulk of our work was in the clubs, the clientele of which could be described as the ‘Chelsea Set’, ‘Beautiful People’, ‘Wannabes’, The Hip Brigade’, etc. who were there mainly to look at one another, checking out fashion, the style makers, and who was ‘on the scene’! The fact there was a band playing was almost incidental to the event, it was seen as a little un-cool to get into the music, unless of course a celebrity musician happened to be in the club and sat in with the band, or a famous act played a bijou gig as a warm-up before going on tour. Audiences at Catapilla’s college and university gigs were better, they contained a high percentage of music lovers who came to the gigs to see the band.

How did you decide to use the name ‘Catapilla’?

Louis LaRose had called the original band ‘Angst’, but after he quit it was essential to give ourselves a new name. Thierry Reinhardt suggested ‘Catapilla Yellow’, we dumped the yellow and became a band with a single word name, which was then highly fashionable. A made up word for a band that made up its own music!

What influenced the band’s sound?

The music that was influencing each individual member of the band influenced the collective sound of both Catapilla albums, our music was the product of our collective influences. We each had our favourite artists and bands, we discussed and shared our preferences with each other. Graham thought Hendrix was God, both he and Thierry were Pink Floyd fans. Anna, as well as being a singer, was a painter and poet, I think her words stand up as pure poetry. Malcolm spent a lot of time intently listening to Leonard Cohen. Dave introduced us to Captain Beefheart via ‘Trout Mask Replica’. Hugh liked American R. & B. and Soul music whereas I was exploring the New Wave of Jazz coming out of America as well as attending gigs in London featuring all the contemporary jazz/ improvisation bands that were around at the time. I think we all loved Tim Buckley. The same thought process, namely being original, that went into the creation of the musics we all listened to was applied to how we played and composed.

Did the size of audiences increase after the release of your debut?

No, the band wasn’t together long enough after the release to promote the album, plus, because we were having a serious dispute with our management/agency over their dishonest, lying and thieving behaviour we parted company with them soon after the delayed release of the album in June, 1971. Post release I can’t exactly recall how many gigs we played but it might have only been one or two. Due to the bust up with management and events leading up to this the band members were feeling disheartened and disillusioned, even betrayed, the energy had gone. This led to the band breaking up. So, a lack of gigs, then no band, meant we didn’t get exposure to audiences after the release of both our albums. Therefore, the effect of our albums on audience size wasn’t tested! Ironically, the size of Catapilla’s audience has increased in the decades after the band’s demise!

How did you get signed to Vertigo records?

We didn’t, we auditioned for Patrick Meehan Jnr from Worldwide Artist Management, an independent company. After signing with them they recorded us, they then licensed the recording to Vertigo.

What’s the story behind your debut album? Where did you record it? What kind of equipment did you use and who was the producer? How many hours did you spend in the studio?

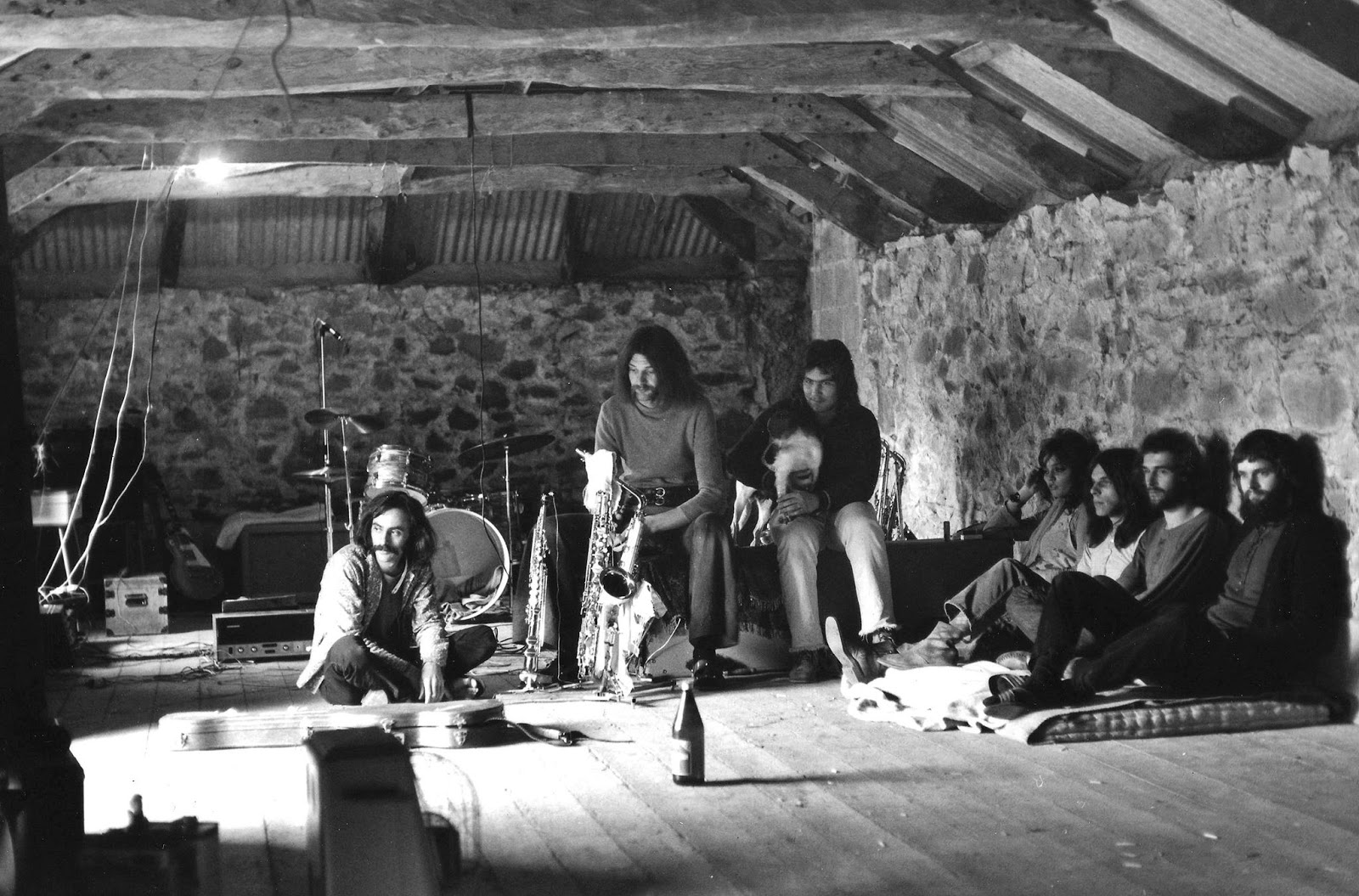

Patrick Meehan Jnr. wanted to record an album almost immediately after signing us. The band was working on new material but there was not enough for an album. Anna Meek’s parents owned an old farm house near Cockermouth in the Lake District, so the band took up residence for two weeks and completed the writing and practicing of new material. On returning to London it was only a very short time before we were in the De Lane Lee studio in London. We recorded onto an eight track Ampex machine using one inch tape and Patrick Meehan Jnr was our producer. The whole exercise was done in great haste, in less than three days. For the band two days, then the third day for Patrick to mix and master, which none of the band members were involved with. In the morning of the first day, playing live as a collective, the band laid down the bed tracks. In the afternoon we overdubbed the solos and doubled some of the horn lines. The second day was for Anna’s vocals plus a short Hammond organ overdub played by Graham’s friend Bob Andrews who was then a member of Brinsley Schwartz.

Please share your recollections of the sessions. What were the influences and inspirations for the songs recorded?

Patrick’s Meehan’s desire to simply get the job done as quickly as possible could be described as cavalier, he was happy to overlook some pretty serious cock ups we in the horn section made on the twenty four minute suite ‘Embryonic Fusion’. It is a very tricky piece, with a series of time signature changes, plus tempo changes between sections. I had to argue with him in order for him to agree to us coming in early on the second day to redo some of our section parts and for me to add an alto sax part that linked the final two sections. I’m so glad I did, just imagine having to keep hearing over and over mistakes we made all those years ago!

Side one of the first album represented the earlier sound of the band but the suite on side two was influenced by the developing trend of some progressive bands to extend their material to lengths that could be described as symphonic. Today that idea might seem pretentious, but when you break down the form of Embryonic Fusion it is actually a series of unrelated elements cobbled together and presented as one single composition. In fact it created settings in which individual members could express themselves with confidence.

Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

Naked Death, Tumbleweed and Promises were songs the band had played before Anna and Graham joined the band. They were extensively reworked for the album with a long section inserted into Naked Death for solos and in Promises a saxophone section interlude that added an unusual textural variation within the song. Embryonic Fusion was written during the time the band spent at the cottage in the Lake District.

Graham worked out most of the harmonic structures, and as he progressed, would present them to Thierry who then wrote the melody and harmony parts. I was given a section to write something for but my approach was much looser, a descending ground bass ostinato punctuated by increasing intensity saxophone accents. Anna wrote the lyrics and it was recorded in two sections. Section one was a tour de force for our drummer Malcolm Frith who was magnificent in building the energy and complexity right to its conclusion. Then in the second part we all had to deal with the time signature changes! (I’ve never been a fan of time signature changes, or odd time signatures, the drummer John Stevens, who I worked with extensively during the seventies, told me he could spend the rest of his life exploring four/four and still find the possibilities for new invention inexhaustible.)

“I was searching for greater freedom in my playing, freedom that might allow me to express myself more immediately, passionately and directly.”

How pleased was the band with the sound of the album? What, if anything, would you like to have been different from the finished product?

Although I can only speak for myself, the general impression as I remember it was that we were simply pleased to have recorded an album and have it released on the Vertigo swirl label. I thought the mix was a bit rough, as was the overall sound, but this merely reflected the haste with which the album was recorded and mixed. Had we been allowed more studio time a greater degree of musical refinement could have been achieved. Anna was not in a great psychological state when we recorded this album and did not respond at all well to the pressure and time limitation placed on her. A more sympathetic approach from the record company would have allowed her to achieve a better result!

Your playing really adds a very special vibe to the album.

I was but one voice in the collective, I believe that whatever ‘vibe’ listeners hear is the product of the disparate range of influences brought into the collective by its personnel. All I can say is that during this period of my musical development I was searching for greater freedom in my playing, freedom that might allow me to express myself more immediately, passionately and directly.

Was there a certain concept behind the album?

Other than what I’ve already talked about regarding the length of Embryonic Fusion, no! I must emphasise that this album, and also our second album, were prepared and recorded in very short periods of time. The time and cost limitations left no room to plan and build into our albums a deeper connecting narrative or more inter-related story/music dramatic arc.

How about your second album? ‘Changes’ was released a year later on the same label (Vertigo). What are some of the strongest memories from recording the second LP?

‘Changes’ was made because Catapilla had to fulfil the terms of its recording contract, which was for two albums. In the summer of 1971 the band spent a week in Cornwall, at a remote farmhouse near St Keverne, where we worked on material for the second album.

However, not long after we returned to London we organised a meeting with our management/agency during which we aired a long list of grievances regarding their dishonesty and mis-management. Nothing was resolved, they walked out of the meeting and subsequently cancelled the contract we had with them, which is why no promotional gigs or tours were organised after the album release in June 1971. At this point, the band, terminally demoralised, broke up, we all went our separate ways. The way we had been treated by our management/agency had destroyed any desire to carry on. For instance Graham and I found day jobs at a hospital in Chelsea.

Some time after this event Patrick Meehan Jnr contacted Graham to inform him that Catapilla would be in breach of its recording contract if it didn’t make a second album! A meeting was hastily arranged at which Patrick Meehan Jnr and his father Patrick Snr were present with Anna, Graham and myself representing Catapilla. We told the Meehans the sorry story behind our demise and found them sympathetic and supportive. They advised us they would pay for rehearsal time, all we had to do was reform the band and write an album’s worth of new material!

Not all the musicians from the original line-up were available, also, for the sake of just getting the job done it was easier to work with a smaller band. I invited my friend Ralph Rolinson in on keyboards and we advertised for a drummer and bass player. Drummer Brian Hanson answered the ad and got the gig. Eventually, after Graham, Anna, Brian and myself were well into working up new material a friend of Ralph, Carl Wassard, who lived in the same house as him, came in on bass. He was in fact a guitarist but went out and bought a bass in order to play on the album. I can’t remember exactly how many weeks we spent rehearsing but I can remember the intensity with which we worked as we pulled this new band together and wrote an album’s worth of material. Rather than a cottage in the country, this time the rehearsal studio was in Wandsworth, so going in every day was more akin to a day job.

The album was recorded in December 1971 at the Marquee Studio in Soho. They had a sixteen track machine recording onto two inch tape. As with the first album the band laid down the bed tracks by playing collectively. Anna joined with us providing guide vocals, later adding her parts separately on a dedicated track. I enjoyed these sessions much more than our previous outing as the atmosphere was far more relaxed, we had more studio time, and the relationship we had with our producer Colin Caldwell was friendly and constructive.

The overall sound is quite different. The vocal delivery became much more theatrical. The sax playing is absolutely stunning! How would you compare it to your debut?

Producer Colin Caldwell was responsible for the album’s sound, he certainly didn’t hold back on the application of tape echo and reverb. I would have preferred a drier mix and Anna was upset by the effects Colin used, she thought they obscured her lyrics (they do!) and as we progressed with the recording she got so upset she refused to participate further, which is the reason the last track is an instrumental! It’s regrettable this happened as Anna was far more confident about her singing and overall part in the new creative team. Her psychological disposition was more robust than the year before which was reflected in her improved and controlled vocal delivery. During the life span of Catapilla I’d used this period to do some serious saxophone practice. I love the ‘absolutely stunning’ compliment, thank you. I’d given up my day job even before we went off to rehearse for the first album. All my practicing must have paid off because I consider my playing on the second album shows an improvement to that on the first.

Some listeners prefer the first album, others the second, I definitely preferred the second. The second line-up worked well together both musically and personally. At rehearsals Graham, Anna and I introduced our suggestions to each other and simply tried them out, often jamming for hours before getting the elements to jell. I’ve always preferred this collective method of song composition as it allows the participants strengths to develop and be given voice in the collective sound of the ensemble. This way of working was so different to how the first album’s material was composed and rehearsed. In my opinion something else really important happened through the process of rehearsing and recording the second album, namely – Anna and I developed a fluid and sensuous conversational style of call and response in the music that absolutely sets this album apart from the first one.

Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

On ‘Reflections’ my wah wah soprano saxophone is featured strongly. I was influenced by a King Curtis record on which I heard that effect used for the first time. Because we were given more studio time for the second album we could go back to tracks and overlay added parts. Both Graham and I added extra parts in ‘Reflections’ and ‘Thank Christ For George’. I used my new gadget, an octave divider, and my wah wah pedal on ‘Charing Cross’. I believe the canyon size reverberation Colin put on Anna’s vocals on this track rendered her lyrics impossible to understand, and was the final straw for Anna. My solo soprano saxophone link in this same track is also awash with echo! As far as I can recall the instrumental ‘It Could Only Happen To Me’ was recorded in the old fashioned way, the band played the song live in the studio and after a couple of incomplete ‘takes’ we nailed it. I know I put my part down in one take because my friend Stephen Pearson, whose Selmer mk.6 tenor I borrowed for the session, was in the studio when we recorded it. He stood beside me, and at the end of the pastoral introductory section grabbed my soprano saxophone from me and swopped it for his tenor.

Last year I bought the vinyl re-mix that George Martin’s son Giles produced from the master tapes of Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I was overwhelmed by the stunning result. Oh to be able to produce a re-mix from the master tapes of ‘Changes’ today.

What was the first song you composed?

Regarding song writing, I’ve always been happier to collaborate. That’s what I did on both Catapilla albums and that’s what I’ve done right up to the present day. I wrote a few songs for a band I played in with Nick Stephens (John Stevens’ Away electric bassist) in 1974 and much later I’ve written songs that have been recorded by a couple of the Ska bands I’ve played with in Australia. My main game, what I find most satisfying and rewarding, is improvisation, which can be thought of as collective real-time composition.

Were you inspired by psychoactive substances like LSD at the time of writing the albums?

What’s the old adage, ‘if you remember the 60s you weren’t there’! (I think we can include the early 70s). Well, I was there and I can remember a surprising chunk of it, but then I wasn’t much of a drug user. Marijuana was the substance preferred when we were working on Embryonic Fusion at the house in the Lake District. On these sessions I can’t recall anybody using LSD. When we were in Cornwall, rehearsing for the second album with the original line-up, Thierry, Graham, Malcolm, Hugh and myself took an acid trip. The other characters had used acid before, the actual person referred to as George in the ‘Changes’ song title ‘Thank Christ For George’ had for ages been saying to me “you’re ready for it man”. Thus convinced, and with ‘safe’ people around me, I had my one and only LSD trip ever! I vividly remember many of the details of the trip, but the funny thing is, the only chunk of my time with Catapilla that I have absolutely no recollection of is the details of the music we played during that whole week we were down there. Just think, if I’d been an acid freak this would be a very short interview! Some members enjoyed recreational use but I think it a general truism to say that hallucinogenics didn’t play a part in the creation of our music or the message of the music. We were not a band advocating the Timothy Leary premise of ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’.

What happened after the band stopped? Were you still in touch with other members? Is any member still involved with music?

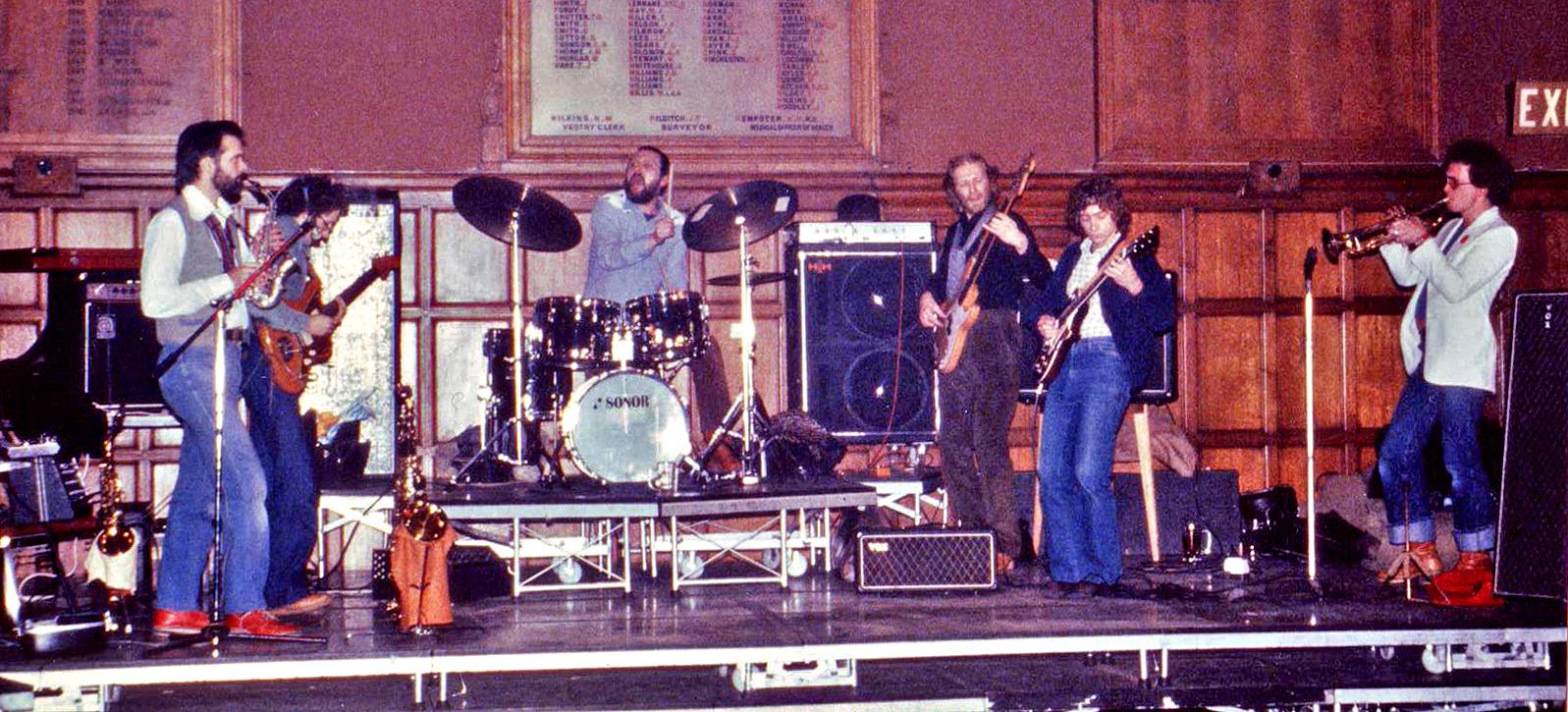

For me, the experience of rehearsing and recording ‘Changes’ had been, despite Anna’s reaction to the recording process, a happy and fulfilling one. Nevertheless, I had absolutely no desire to keep going with the band, or any band, after we walked out of the studio on that Wintery December day in 1971. The recording obligation had been met but the disgust I felt towards the corrupt and dishonest machinations within the ‘Music Business’ left me with no desire to continue as I had done in the past. A couple of years after the demise of Catapilla I joined up with Anna again in a small band specially assembled to play her compositions. This unit played a few gigs and recorded four songs (copies of which I still have). In the interim period she’d had singing lessons with Cleo Laine, written a number of songs and found an agent. Unfortunately, nothing further developed, but in 1975 we exchanged letters. She was then studying music at The Guildhall, London majoring in singing. We didn’t stay in touch and I lost contact with her, which I regret. Up until the end of 1976 I lived in Abbey Road, a few hundred metres down from the famous studio. Ralph lived close by – only about a mile from me, so I would often call in to have a chat. He was the person who most of all wanted to keep something going after we finished the recording. When I moved from Abbey Road I lost contact with him. He now lives in a bus in British Columbia (I think), Canada and I chat with him occasionally on facebook. In late 1982 I returned to live in Melbourne, Australia. Up to then I‘d kept in touch with Graham Wilson and Thierry Reinhardt. At a gig with John Stevens’ Away at the Plough in Stockwell, probably in 1978, Brian Hanson turned up. He wasn’t playing in a band, he was concentrating on song writing and trying to sell his songs to publishers. He invited me to his house in South London where I laid down some saxophone parts for him. Over the last few years, whenever I’ve been in Britain, I’ve spent time with him, in fact, I’ve done quite a bit more recording with him on his songs. I played in a band, ‘Body Heat’, with Graham Wilson prior to joining ‘John Stevens’ Away’ in 1976.

Later he went into the kitchen fitting business and his guitar disappeared into a cupboard. On my visits to the U.K. when working with Mother Gong (and Gong in 1994) I always spent time with Graham, from Australia I wrote and phoned occasionally, as did he, we always stayed in touch. He developed cancer in the early 2000s, went into remission after initial treatment, but regressed and became terminally ill in 2003 so I made a special journey to see him in October 2003. Whilst there his wife showed me numerous Catapilla references and reviews she’d found online. This was the first time I realised there were people out there in the world who were interested in what we had done all those years before. Before he died in January 2004 I’m so happy Graham got to see that our musical adventures were gaining interest amongst prog rock aficionados and receiving positive critical responses. It washed away many of our bad memories. In 1994 Thierry became a music teacher at Goldsmiths College in London, I saw him in that year but didn’t reconnect with him again until 2014 by which time he was seriously ill with leukaemia. I saw him again the following year but he died in January 2016.

I have no knowledge of what happened with other members who had played in the different combinations of Catapilla.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

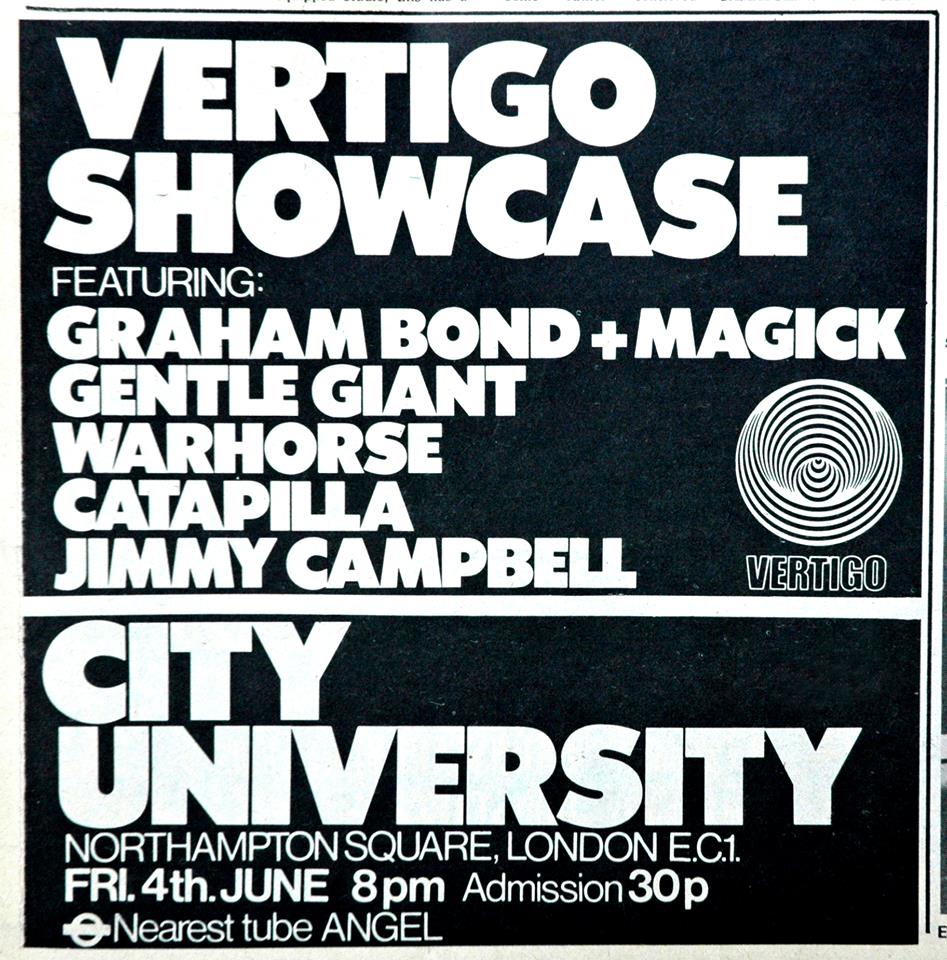

I had many good times in the lifetime of Catapilla, but I consider the highlight to be the seriousness with which we as a group of individuals took on the challenge of creating an original and unique music. The personal challenges I faced in the making of those two albums put me on a steep learning curve, the process of which has had continuing benefits. Catapilla was the first professionally minded band I’d been a part of, at the time it’s what I wanted to do. I believe the passion, dedication and hard work we put into the project added a quality discernible today, our honesty, commitment and integrity shine through giving the music what I believe to be a timeless quality. ‘It Could Only Happen To Me’, the song Graham and I co-wrote, is the song I’m most proud of. I remember Graham and Ralph got stoned before we recorded it, but I lay under the grand piano and did deep breathing exercises, which left me relaxed and calm. I definitely felt in control of my situation, the swop from soprano to tenor saxophones mid take worked flawlessly and the flow from beginning to end left me feeling very satisfied. A gig that sticks in my memory was when we played at the City University on Friday 4th June 1971. It was a Vertigo Showcase featuring Graham Bond + Magick, Gentle Giant, Warhorse, Jimmy Campbell and ourselves. Graham Bond’s band had their own dressing room, from which we heard Graham on alto sax playing Charlie Parker tunes at breakneck speed whilst being wildly cheered on by band members. (I’m sure they were on something!) The look Thierry and I gave one another belied the unspoken comment, ‘shit, we’ve got to get up on the same stage as this guy’. However, our set went well and I looked forward to Graham Bond’s set, but what a disappointment. He brought the alto on stage, put it on top of his Hammond organ, and didn’t play a note on it throughout his set. Instead what we got was a massively distorted Hammond sound that was so loud it drowned out his vocals!

Is there any unreleased material?

Not that I’m aware of! Definitely nothing from the first album. I believe everything we recorded for ‘Changes’ was used, and no live recordings. As part of the creative process, that is, in order to preserve ideas that came out in the long jam sessions we had at the rehearsals prior to ‘Changes’, I recorded some of the rehearsals on an open reel machine. Two short segments survived, they are useful to illustrate how we developed the songs.

In the 1970s you studied improvised music with John Stevens and Maggie Nicols. What are some of the strongest memories from your collaboration? Did it change the perception you had regarding music?

As previously stated I had no intension of continuing with Catapilla after completing the Changes recording. My bubble was burst, the spirit of the 60s were over and the shock of such gross mismanagement left me with no desire to engage in any musical activity that involved the commercial music business. But what to do? My interest in music was unwavering, so I went in search of the music and musicians that interested me. Quite soon after completing Changes, at the beginning of 1972, I went to hear John Stevens with the Spontaneous Music Ensemble (SME) at the Phoenix Jazz Club in Cavendish Square London. I’d been a fan of SME for years and had seen them many times. A friend had told me that John ran improvisation workshops, so at the end of their gig I introduced myself to him and asked about his workshops. Being a fan and follower of his music I definitely felt nervous approaching him but found him to be friendly and accessible. He invited me to join his weekly Inner London Education Authority (I.L.E.A) Improvisation workshops that he was running in Bethnal Green, which I immediately did. Maggie Nicols also taught on this same course, with Maggie taking one week, John the next. Maggie’s nights were always fun, she incorporated movement and drama into her approach. She was then a member of the Worker’s Revolutionary Party, and as a member of her workshop group found myself on one occasion performing on late night BBC2 T.V. a musical drama representing a Marxist dialectic. On another occasion, at London’s Alexandra Palace, along with fellow workshoppers and musician comrades from the Party, performed workshop pieces and a stirring rendition of the Internationale for thousands of Party members and delegates who had arrived by the coach load from all corners of the country. John Stevens’s workshop exercises used the most basic elements of music orthodoxy, such as tempo and dynamic control to develop skills of immense value, not only to the improvisor, but to a musician participating in any musical setting. He taught us how to listen, how to be sensitised to fellow group members and play appropriately within the ensemble. John fully understood the power of revelation that his workshop methods could release in the individual but never mentioned that that was his intension. Through rigour and discipline he guided and encouraged us to a point that caused us to experience our own revelations. What a phenomenal teacher, in all he taught me he fully understood the depth of experience possible, but let me discover for myself my own personal revelations. In his own words, “If you want to see a vision – see a vision”!

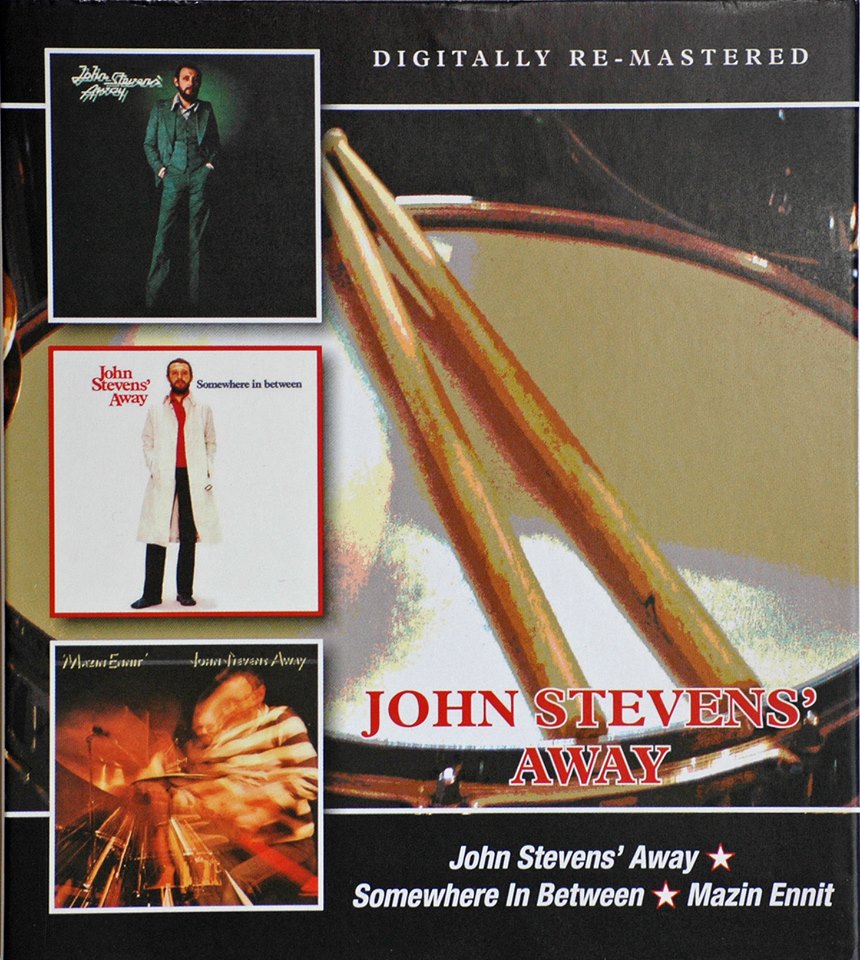

You appeared on Spontaneous Music Ensemble’s album ‘SME+=SMO’ (1975) and also on ‘Somewhere In Between’ (1976) and ‘Mazin Ennit’ (1977) followed by John Stevens Dance Orchestra – ‘Ah’ (1977) and ‘Away’s Integration’ (1980). In 1994 you appeared on John Stevens Dance Orchestra’s ‘A Luta Continua’ and ‘Away’s Mutual Benefit’.

In 1975 John Stevens was successful in obtaining a grant from the Arts Council of Great Britain which assisted him in the making of the improvisors orchestra album SME+=SMO. This expanded contingent of musicians was made up of the Spontaneous Music Ensemble, his two workshop groups – the Bethnel Green I.L.E.A. group and the Ealing College Of Higher Education group, plus further guests including Trevor Watts and Evan Parker. It was recorded at a live performance at St. John’s Smith Square, London. I’d been a member of John’s workshop group for four years when he asked me to join him in a reformed John Stevens’ Away in March 1976.

It was a case of being thrown in at the deep end. I had one short rehearsal, which took place after a workshop session, then just a few days later we played a gig at the 100 Club (which was reviewed in the Melody Maker by Chris Welch, who pointed out that this Robert Calvert is “not the Hawkwind chappie”. Funny how even today I am still confused with the ‘Hawkwind chappie’ who died on the 14th August 1988!) The following day we were in Phonogram’s Marble Arch studio recording a single ‘Anni’, which featured John Martyn on vocals and guitar. Away performed an instrumental version of ‘Anni’ on the Old Grey Whistle Test on the 4th May and were the featured band on John Peel’s BBC Radio 1 show broadcast on the 7th June. On the 15th and 16th June we recorded the album ‘Somewhere In Between’ at Phonogram’s Marble Arch studio. Three weeks later we were out on tour as special guests with fellow Phonogram recording artists The Crusaders! Our second single, ‘Can’t Explain’ featuring Terri Quaye, was recorded at Phonogram, Marble Arch on 25th July. During the first two weeks of October we toured Britain, sharing the bill with the Steve Hillage Band, promoting our ‘Somewhere In Between’ album. After a BBC Radio 3 Charles Fox Jazz In Britain broadcast on the 18th October we were back in the Phonogram studio a week later (25th and 26th October) recording ‘Mazin Ennit’. Steve Lillywhite was our recording engineer and co-producer. An extra day for recording and mixing was added on Sunday 14th November. Although Steve and John were producing the mix this was the first time I’d ever sat in on a mixing session and been asked my opinions. As far as the studio time was concerned I recall it seemed long enough, we played live, baffled off from one another, playing to a headphone mix and making sure there was good visual contact between us. We were never over rehearsed since John liked the music to be fresh, in fact he presented the song ‘God Bless’ to us on the day we recorded it. He’d sung the melody into a portable audio cassette recorder the night before and had me out in the corridor learning the melody immediately prior to going into the studio to record it. Because at the time the Musicians Union stipulated that music broadcast by the BBC must be recorded in the BBC’s own recording studios John would use our BBC sessions as warm ups, try outs, for album material, hence the ‘Jazz In Britain’ broadcast a week before the album recording.The music press were very kind to this album, we got rave reviews. Unfortunately for Away the good reviews didn’t translate into good record sales, consequently we lost the Polydor (Phonogram) contract. Incidentally, both albums were released on the Vertigo label and in 2015 were re-released on the BGO label.

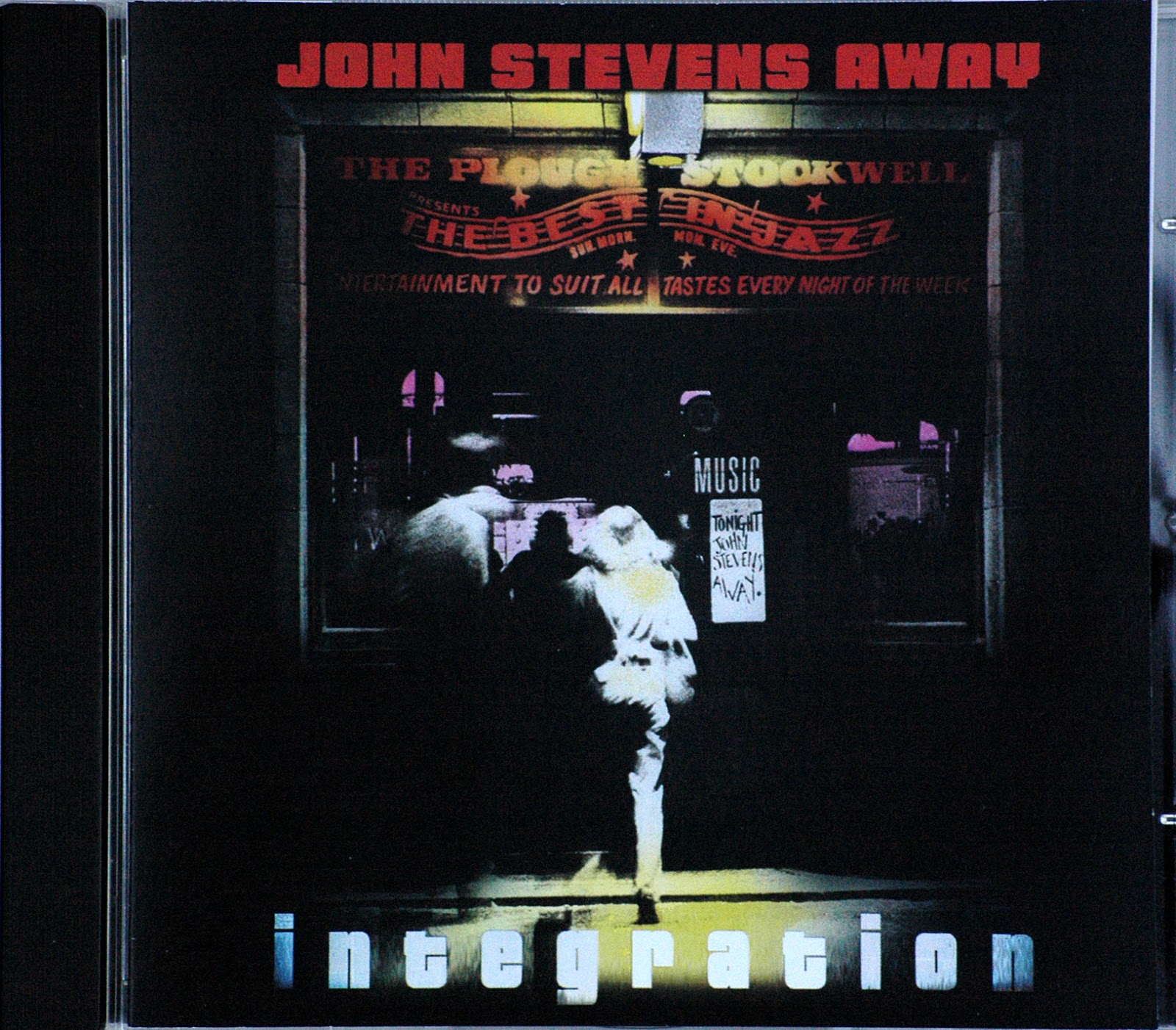

The Berlin record company ‘Vinyl’ were responsible for releasing Ah! The John Stevens Dance Orchestra. It was recorded at Riverside Recordings, Chiswick, London in September 1977 and released in 1978. Its personnel were the AWAY band with the addition of the African American pianist/organist Jeff Young. In my time with Away one further album was released, ‘Integration’.

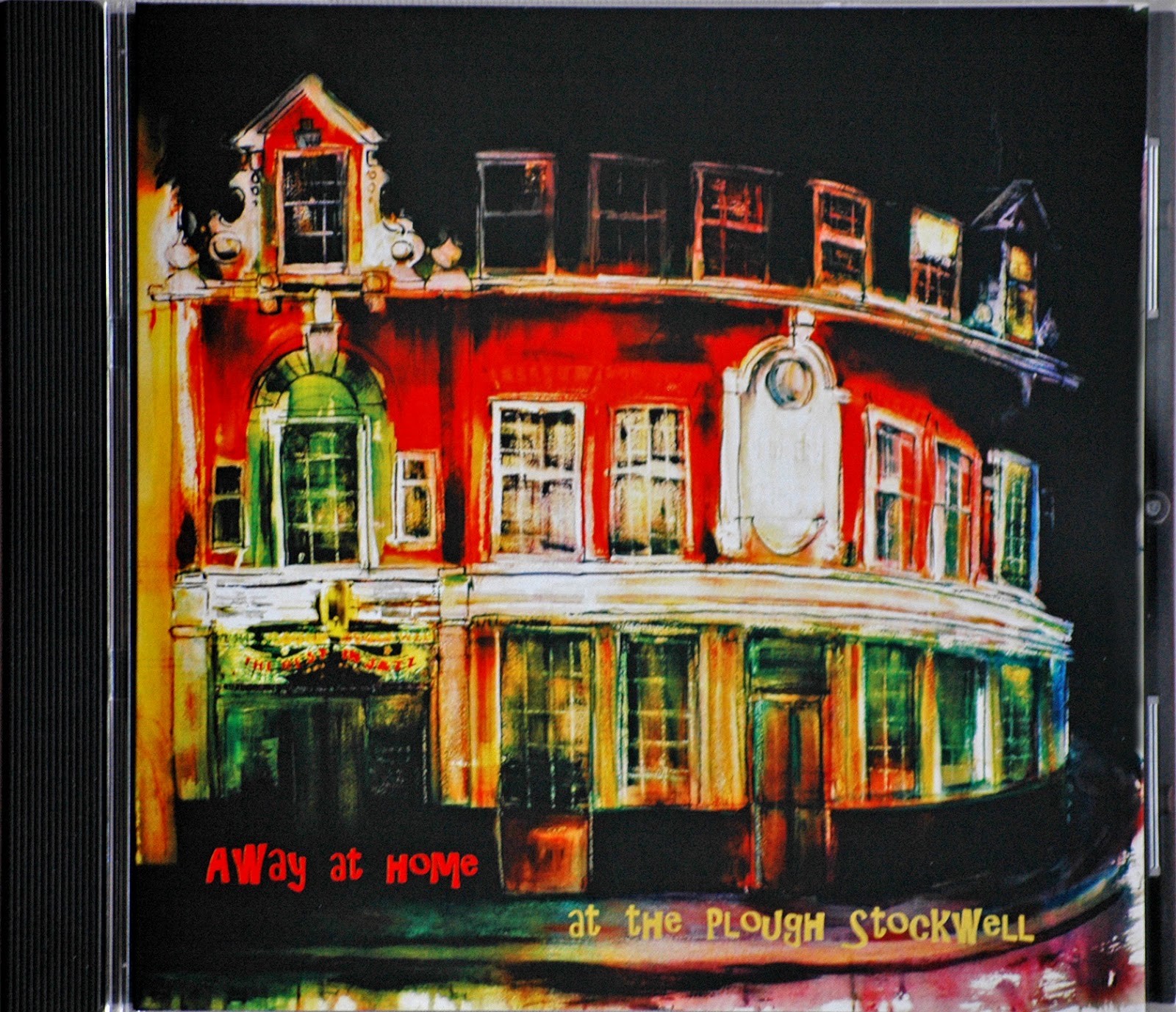

The source came from an audio cassette recording I had made of a gig at The Plough in Stockwell London on the 25th February 1978, (I still have in my possession a number of taped Away and John Stevens Dance Orchestra gigs). The sound on my tape was enhanced and cleaned up at Riverside Recordings and released on the Philadelphia ‘Red Records’ label in 1980. Away’s electric bassist Nick Stephens, who runs his own ‘Loose Torque’ label, digitally remastered ‘Integration’ and rereleased it as a CD a few years ago. He has since mastered another of my live Plough tapes, this one from 4th August 1978, and released it as ‘Away at Home – at the Plough Stockwell’.

When in 1994 I visited John at his Ealing home he gave me a copy of ‘A Luta Continua’, an album made up of different BBC broadcasts dating from 1977,1979 and 1981, with me playing on five of the nine tracks. It had only just been released and John was very happy to have finally obtained from the BBC radio broadcasts from the Away and Dance Orchestra days, material he had for years been trying to get hold of. Tracks 1 – 4 feature the band that the evening before the BBC recording date (24th October 1979) had performed at London’s Roundhouse Theatre. At this gig, as well as John on drums, we were joined by Phil Collins. Unfortunately Phil was not available the next day and so missed the BBC session.

I suspect these two tracks to have been part of a Dance Orchestra broadcast. John Stevens died on the 13th September 1994, he was only fifty four. I’d had a drink with him at his local pub ‘The Greystoke’ just a few weeks before he died but was on tour in Italy with Gong when his funeral was held. I was shocked and distraught and I felt a deep sadness for years after he died. I love John for what I learned from him and for the experiences we shared.

In the late eighties you started to collaborate with members of Mother Gong. What was your relationship with members? I find their music extraordinary, Daevid Allen had an amazing vision and huge impact on the music scene back in the 60s/70s. How was it to collaborate with them?

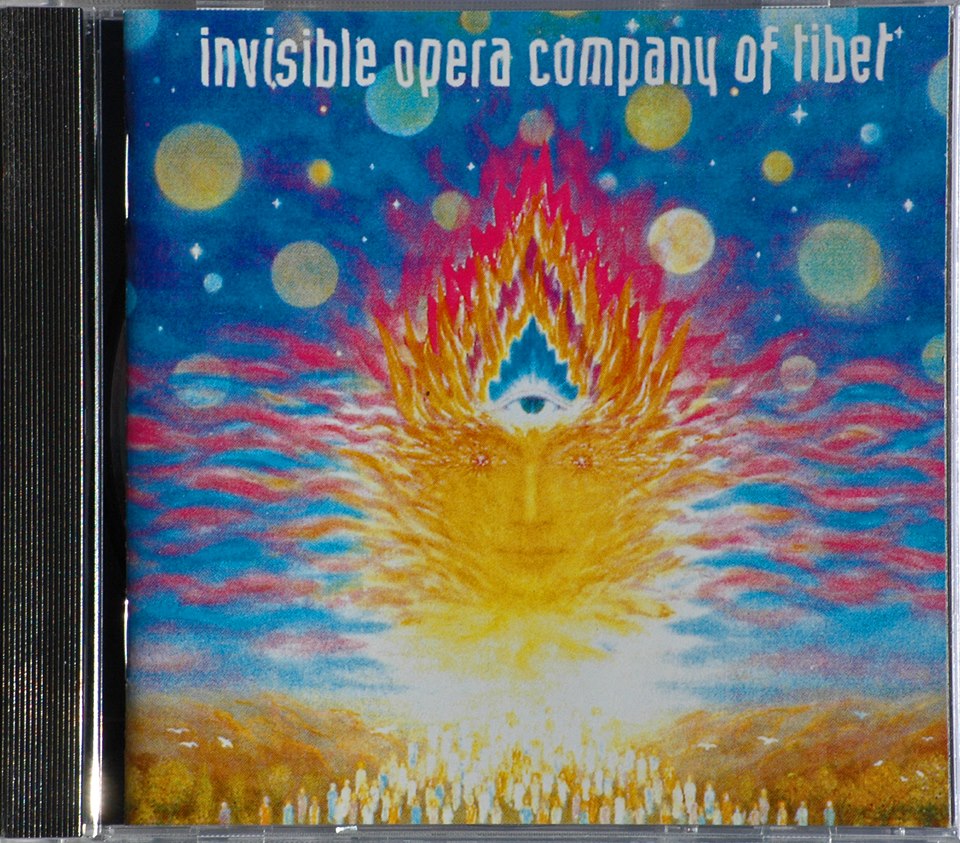

On the 21st July 1987 I was booked for a recording session with a Melbourne Afro-beat band “Kalimba’. The recording engineer was Harry Williamson. I was early, arriving before any of the other musicians, which gave Harry and I the opportunity to swop brief background information. I learned he was married to Gilli Smyth of Gong fame, and, “Had I heard of Gong?”, he asked me. Surprisingly, in Australia very few people were aware of Gong, (an ongoing situation) with their records never being released or promoted here. Naturally, having lived in London during the early Gong years, I was very aware of Gong. My awareness prompted Harry to play me some music he was working on, in no time at all I had my saxophone out and was laying down some impromptu parts! The session I was booked for went on for two days, on the second day, after I had finished the Kalimba recordings, Harry asked me to stay behind and sit in on a session he had organised for that evening with friends of his, some of whom were members of the Australian version of The Invisible Opera Company Of Tibet. He asked me “can you improvise?” Not knowing of my history with the John Stevens and Maggie Nicols London workshops I could confidently answer in the affirmative. The session recorded that evening eventually was released on the 1991 Voiceprint CD ‘The Invisible Opera Company Of Tibet’ as the track ‘Gorilla’. đ

Not long after, at another session Harry invited me to, the drummer was Rob George. Both of us arrived early, he already had his kit set up, so with me on soprano saxophone we jammed together, which brought smiles to both our faces. Because Harry, Rob and I found it easy to improvise together Harry suggested we visit his home studio, meet Gilli, and record with her, which we did. Regular Friday evening sessions developed from this first meeting, and over a period of about eighteen months, Harry had accumulated a large body of recorded works. Towards the end of this period the bassist Conrad Henderson joined us. Because this line-up was stable, recording a vast body of work over a seven year period, this is the grouping Gilli called the classic Mother Gong band. I met Daevid Allen for the first time early in 1989 at Harry’s Spring Studio in Melbourne. Harry had negotiated with Dave Anderson’s Demi Monde label an album deal to be shared between Daevid and Mother Gong. Daevid had new songs to record but needed a band. He knew a bass player in Melbourne, and his then partner Wandana Arrowheart played the harmonium, but used Harry, Rob George and myself to complete the line-up. The resulting album, made up of selected tracks from the accumulated Mother Gong material and Daevid’s newly recorded tracks, was ‘The Owl And The Tree’, released late in 1989. Dave Anderson offered to record an album with Mother Gong at his Foel Studio in Wales, so in late July 1989 Rob George and myself flew to the U.K., with Gilli and Conrad Henderson joining us a few weeks later.

Harry was already at the studio working on two of Daevid’s projects, a Gong Maison album and Daevid’s solo album ‘Australia Aquaria/She’ (two tracks on which I play).

The time I spent in Wales recording the Mother Gong album and having the opportunity to play on Daevid’s tracks was very special for me. It was the first time since 1982 I’d been back in the U.K. and the creative atmosphere I found myself in was amazingly inspiring. It produced my favourite Mother Gong album – ‘Wild Child’, not released until 1994 but well worth the wait.

Meeting up with Harry Williamson and Gilli Smyth and forming a new Mother Gong band with Rob George and Conrad Henderson as well, gave me the opportunity to do what I really loved, that is – improvising. It was usual for us at the beginning of a session to read through the poem Gilli wished to record, decide a musical mood, then improvise behind her. Daevid organised his music more conventionally, but nevertheless, allowed his musicians to find their own space and express their own voice within his songs, a formula that added richness to his compositions. On the 8th and 9th of October 1994 ‘GONG 25 – the 25th birthday party’ gig took place at the Forum Theatre, Kentish Town, London. Didier Malherbe, the band’s long standing flautist/ saxophonist joined with a re-united Gong band for these two gigs. In the months prior to this event Gong had toured through seven European countries, for these gigs Didier wasn’t available. From May through to October Mother Gong had dates booked in Britain (one of which was the Glastonbury festival) and America. We were also included on the same bill as Gong on all the European dates so Daevid invited me to fill in for Didier. It was a thoroughly enjoyable experience, the band was great, the songs were great and Daevid’s charismatic stage presence was a joy to behold.

During the five month period we were away from home there were periods of down-time. On one occasion between tours Robin Ayling from Voiceprint suggested Gilli record an album. Gilli together with Steffe Sharpstrings (Stephen Lewry, who was then Gong’s guitarist and had his own home studio) were the creative team on ‘Glo Even As We’. My soprano saxophone appeared on two, maybe three tracks, I can’t accurately remember, not being closely involved in this project.

Daevid lived in Northern New South Wales and would occasionally come down South to visit or work on projects at Harry Williamson’s Spring Studio. When he was in Melbourne I would contact him and ask that if he had a spare afternoon I would I pick him up and bring him to John Howley’s studio (John and Daevid went back a long way, indeed, right back to the late 1960s) to have a jam with the Howley/Calvert/George Trio.

This happened on two occasions and I recorded both of them, a three and a half minute section of one of my recordings appears on Daevid’s ’22 Meanings – The Art Of The Glissando Guitar vol.1’ CD which was released in 1998.

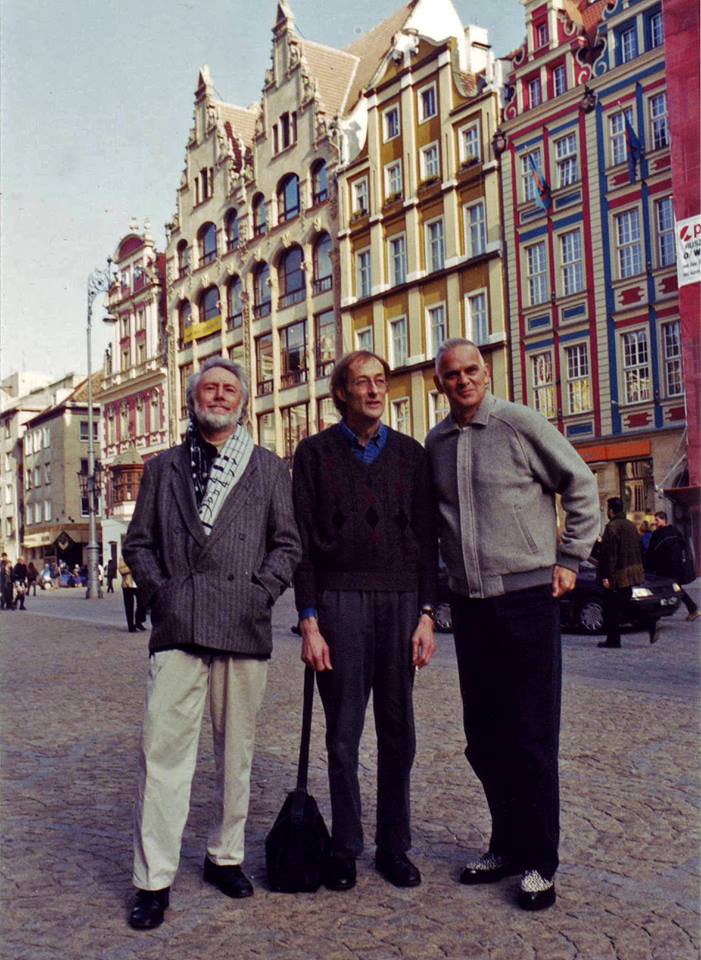

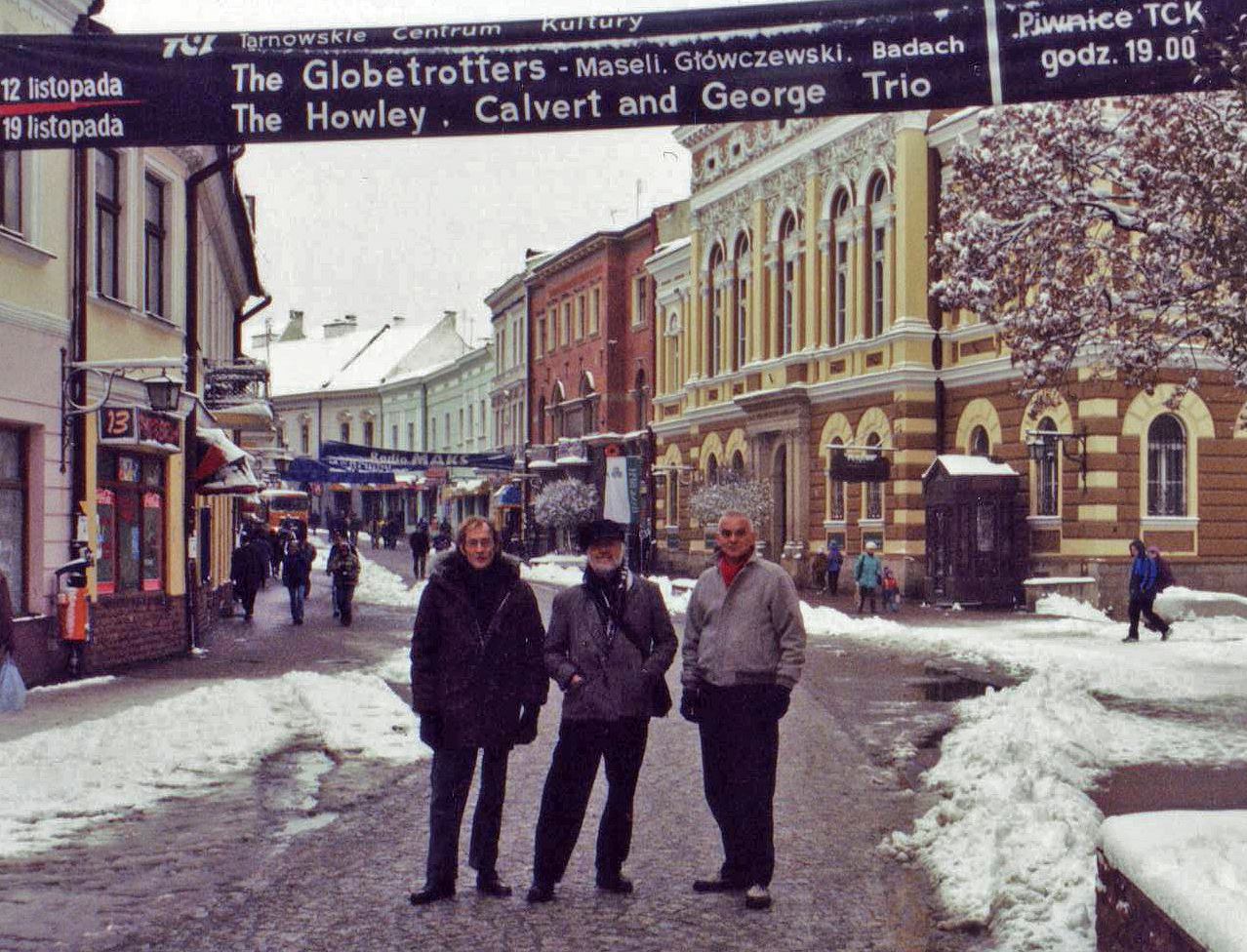

Between 1994 and 2008 you played in the free form improvising group The Howley/Calvert/ George Trio together with John Howley on piano and vocals and Rob George on drums.

John Howley is a renowned artist with a secondary passion for playing the piano in a most unusual, energetic and original way. He also has a very fine voice. I met him as an artist when in 1990 I went to one of his exhibition openings. He told me of his passion for music and invited me to his large studio to have a play with him. John was simply incapable of playing the same thing twice, making him a perfect partner for an improviser like myself. In the years up to 1994 I played with him in a number of combinations of musicians, poets (including Gilli Smyth) and dancers, but just days before I left for France in May 1994 the drummer Rob George, my colleague from Mother Gong, played with John and I at a concert at Montsalvat, an artist colony in Eltham, Victoria. Whilst I was overseas Rob and John got together regularly. On my return in October 1994 I joined with them thus creating the Trio. Although in Australia the Howley, Calvert, George Trio was intentionally, even deliberately ignored, I consider it’s where I achieved the pinnacle of my musical ethos.

This is where my life’s experiences, understanding and expression of friendship, as well as musical knowledge came together. I think an explanation is warranted: As I see it, the processes of improvisation can reveal many of life’s truths on many different levels. In the Trio, apart from the musical voices and rhythms we guided to a sort of synchronicity, it exposed other aspects of ourselves, and of our shared human condition generally, things outside the music; for example, the psychology of perceptions, the nature of personality and ego, the understanding of strengths and weaknesses, the implications of dedication. Playing in the Trio, is where the depth of feeling expressed could leave our psyche exposed and vulnerable, we needed to be absolutely confident we could trust our colleagues to acknowledge and value this level of personal exposure and respond accordingly, with respect, even reverence, so we might bring our expressive possibilities toward a coherent and focused end. We needed to feel safe in situations that reflected both musical qualities and human virtues. Here, through this complex process of improvisation, (what I consider to be the purest form of music making), it was possible for an open ended system to be realised that offered, as an allegorical example, the vision of a potential society. Now, that’s revolutionary! Generally, with all the integrity and professionalism that the years of work, study and dedication I have given to this discipline, I believe that I’m closest to the Truth when I’m being both faithful and truthful to myself as an artist and as a whole person. This is where my understanding of myself becomes clarified; this is real as far as I know anything. The lack of acceptance of the Trio in Australia was a hard pill to swallow. It took two visits to Poland (1998 and 1999) to vindicate my belief in the venture. In a variety of venues ranging from clubs, culture centres, concert halls, even the Lodz Opera House, we performed our truly unique music and didn’t disappoint a single audience.

What were some of the bands you enjoyed in the 1960s and 1970s? What’s your opinion of Pink Floyd’s debut, Soft Machine and the Canterbury scene in general?

As I said at the beginning, my love of music began in the mid 1950s with the birth of Rock ‘n’ Roll, I particularly liked Little Richard, Fats Domino and Ray Charles. The first concerts I attended that I paid for myself were local Melbourne Traditional Jazz bands. When the British Invasion of the 1960s hit Australia I was completely hooked. I didn’t miss many acts, seeing the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Manfred Mann, Herman’s Hermits, the Dave Clark Five, Peter and Gordon, The Honeycombs, The Searchers, Sounds Incorporated, Tom Jones and more. I also saw Roy Orbison, who was on the same bill as the Rolling Stones. After I arrived in London in 1967, and plunged into the music scene, quite a few bands grabbed my attention. I loved any band that saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith played in, e.g. John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and Colosseum. I loved the singing of Roger Chapman from Family, I saw Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, Stan Webb’s Chicken Shack, The Nice, and I thought the first light show I saw with the musical act Zoot Money’s Dantalian Chariot was amazing. However, because my main musical interest lay with the traditions associated with the instrument I play, namely jazz and improvised music, I closely followed local bands like Brotherhood Of Breath, Mike Westbrook’s Big Band, Zilla, the Spontaneous Music Ensemble, Evan Parker, Derek Bailey and any visiting American musicians or bands – Roland Kirk, Cecil Taylor, Cannonball Adderley, Thelonious Monk, Art Blakey, Chick Corea, Sonny Rollins, Ornette Coleman, Paul Bley, Steve Lacy, Frank Zappa and the Mothers Of Invention, Sun Ra and his Arkestra. Despite the above statement I must point out that during these times musicians and bands were being encouraged to be inventive and do their own thing – to be original. In my Catapilla days this meant not being influenced by bands in the same genre as us. Thierry Reinhardt, Graham Wilson and Ralph Rolinson were Pink Floyd fans, they bought their records and saw them live, but I have to admit that the only time Pink Floyd blew me away was when I was in Cornwall with Catapilla during that one occasion of tripping on acid! I liked the first two Soft Machine albums, their use of improvisation offered a different approach to song writing, one that I thought was not derivative of American forms, and along with the whimsy of the lyrics and hint of psychedelia created a fresh new sound, one I think of as a regional sound. I think this is what has been classified as the ‘Canterbury’ sound. Although Daevid Allen and Gong have been included into this camp, for geographical reasons, I never saw them as a part of it. Gong began as an Australian/Anglo/French band. Daevid was brought up and educated in Melbourne Australia, a long way from Canterbury England, and to me he was the mastermind behind the Gong phenomena. I also believe that the adventures and the characters inhabiting his Planet Gong creation are reactions to the failed May 1968 Paris riots, insofar as after the Establishment smashed the Revolution Planet Gong represented an escape into an alternative world. Smarter people than me have expanded this theme. Having in 1994 been a pot headed pixie myself and for a brief time been a denizen of Planet Gong all I can say is that I am left with nothing but admiration for the entire Gong family.

You emigrated to Melbourne Australia at the end of November 1982, besides your involvement with Mother Gong/Gong and Howley, Calvert, George Trio what other musical activities have you undertaken?

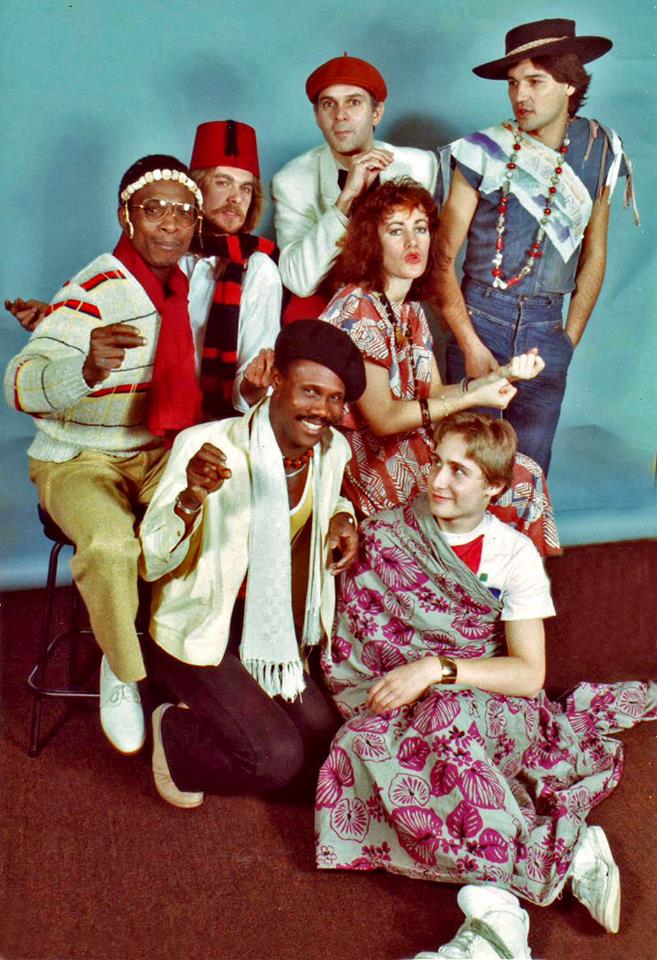

When I emigrated to Australia a second time, I had only just completed my BA (hons) in Humanities, I majored in Music. With a head full of ideas and the dreams of a migrant I wanted to participate in musical activities that had cultural significance. Hmm, this turned out to be a difficult ambition in a country that worships sport and is yet to understand how music can contribute to the making of a national identity. It soon dawned on me that if I wished to be a full-time musician it would not be possible for me to undertake anything of a similar contemporary musical nature to that which I’d been involved with in London. But how to be culturally significant? The thing that defines Australian society is its diversity. To bring elements of this diversity together in a band seemed to me to be the way to forge a music unique to the Australian social milieu. As a result I joined with musicians of mixed gender, ethnicity and nationality to form a band representing this diverse mix, named ‘Asambu’. By far the largest percentage of our repertoire was written by band members, all but one of them contributing songs. Our drummer and percussionist were Nigerian, this introduced a strong Afro-Beat element into the music, making it very dance floor friendly. We developed a loyal local following but neither of the two big Melbourne music agents would take us on.

This fact restricted the ability of the band to reach a wider audience so in 1985 I joined a touring and recording ska band, the ‘Strange Tenants’ and became a full time musician.

This band, influenced by the second generation of ska that came out of Coventry in the mid to late 70s, worked constantly. A typical six week road tour would take us from Melbourne to Adelaide, then to Whyalla (South Australia), then wind its way all the way round the South and South East coast of Australia up to Townsville in Queensland, a distance of about 4,500 kilometres.

Prior to my joining the Strange Tenants this had been their routine for more than three years. The touring took its toll, in 1986, wearied by the hard slog, the band stopped working but didn’t break up. Ever since then we have periodically performed shows. A book and a film will be released at the end of this year dealing with the history and politics of the band, plus a new album will also be released.

Because of my association with the Strange Tenants I have developed a reputation in the Australian ska scene, consequently since 2003 I’ve been a regular member of the ARIA (Australian Recording Industry Association) award winning Melbourne Ska Orchestra and since 2014 a member of the reformed 1980s Melbourne ska band No Nonsense.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

There are some artists I listened to a lot back in the 60s and 70s, like Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart, John Coltrane, Achie Shepp and Albert Ayler, but today the artists I periodically play from my vinyl record collection are Paul Bley’s albums: Turning Point and Open To Love; The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown; anything by Tim Buckley (my favourite is Starsailor); Eric Dolphy’s Out To Lunch; Roland Kirk’s: Rip Rig and Panic. I love the raw energy of Charles Mingus’s albums Blues and Roots and Mingus Oh Yeah. After the death of Cecil Taylor in April I pulled out the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra box set and played the sides featuring him, and was just as amazed as I’ve ever been about this set. I have listening binges on Bird, Sonny Rollins and Art Tatum but my eternal favourites, at any time, and always rewarding listening, has to be Lester Young with Billie Holiday and Lester Young with the Count Basie Orchestra. My two recent CD acquisitions are Billie Holiday and Lester Young – Complete Studio Recordings, and Count Basie – The Complete Decca Recordings. In the Western tradition I still love listening to Mozart’s piano concertos and symphonies, Bartok’s string quartets and Debussy’s orchestral pieces, oh, and Stravinsky’s Symphony Of Psalms. I sometimes fall asleep with the radio on. One early morning, a couple of years ago, I awoke and thought I was hearing music beaming down from heaven! It was the Unthanks, a family folk singing group from Tyneside North East England, featuring the sisters Rachel and Becky Unthanks. What I was hearing was them singing the Robert Wyatt song Free Will and Testament from the double CD album ‘Last and Diversions vol. 1’. I’d recommend anything by the Unthanks, fortunately there’s lots available to see on Youtube.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

I’ve been playing music for fifty eight years! For me it’s never been about being rich (ha ha), famous or even brilliantly virtuosic, it’s been about the sense of community I’ve found amongst the musicians and music lovers I’ve enjoyed the company of and the endless challenge, beauty and mystery of music itself. As I observe the trials and tribulations encountered by our world’s human populations I believe that music, an activity that has the power to break down all barriers and draw divergent people together into a common cause, can be understood to be one of humanity’s saving graces. The writer and mythologist Joseph Campbell said – “I think the person who takes a job in order to live, that is to say, for the money, has turned himself into a slave”. For some reason I don’t fully understand I’ve always intuitively known this to be true, because when in my life I’ve had to work ‘for the money’, I never allowed such a job to get in the way of my musical commitments, and so, in the eyes of others, dashing quite a few promising careers. My commitment hasn’t come without it’s problems, I’ve lived with insecurity, ridicule, even an episode of depression. On the other hand this apparently eccentric life has been edifying and exhilarating. So, besides the actual music I’ve created and performed (the one thing managers/music business cannot steal) the only other point I can make that might have relevance to a younger generation is that once you raise your pursuit out of the context of leisure or recreation, and it becomes something you depend on to exist (a way of life), you can survive, your life will be enriched and you will truly be yourself. Thank you for your questions.

Robert Calvert July, 2018

Klemen Breznikar

Gong are releasing a new album – ‘Rejoice! I’m Dead!’. Interview with Kavus Torabi (vocals/guitar)

Nice interview, one of the best. Calvert is articulate and has a fascinating musical life. It's also good to discover more group's from Rock's golden age.

Best musician I ever worked with and one of the most genuine people you could ever hope to meet.