‘A Broken Heart Would Be Lovely’: Skip Spence and Oar

In December 1968, a young Californian musician walked out of a Nashville recording studio for the last time. Having applied the finishing touches, the slight 22-year-old’s first and final solo album would be released the following year to near-silence. One of many low-budget, quick-fix LPs released in the dying days of the 1960s, it even went on to the rather embarrassing feat of being (for some time) the worst-selling LP in Columbia Records history.

For years afterwards, this young man’s album was condemned to a humiliating, drawn-out death in the bargain bins of thrift shops and dollar stores. But awaiting those lucky few that salvaged it from the back shelves was a record of surprising beauty and true musical honesty.

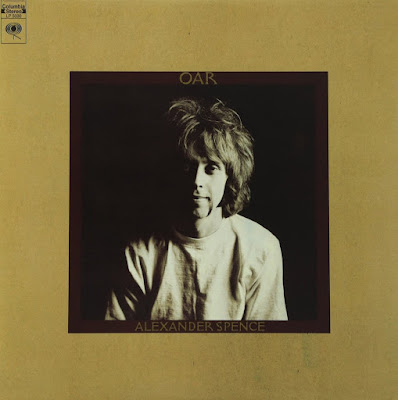

Everything about this album is strange – its cover, for a start. Without any of the self-consciously fantastic images of its contemporaries, it almost has the appearance of a wild-west wanted poster: a central black-and-white photo of a half-shadowed face, bordered by a sandy sepia backdrop and printed in block, distinctly un-psychedelic lettering: OAR – ALEXANDER SPENCE.

For those lucky few, this name was almost certainly not familiar – but it so easily could have been. In the burgeoning Haight-Ashbury scene, Spence – known to his friends and fans as ‘Skip’ – had a reputation as a promising songwriter and a consummate rhythm guitarist. He was even an early member of the pioneering bands Quicksilver Messenger Service and Jefferson Airplane, taking the drumming stool on their first LP, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off. But after taking a trip (in more senses than one) to Mexico with two girlfriends and missing a gig, Skip was fired by the band. Just months before Grace Slick joined and the Airplane went on to rock immortality with Surrealistic Pillow and their 1967 singles, Skip had to leave the gravy train early.

Yet perhaps the greatest missed opportunity of Skip’s short career was his subsequent project, Moby Grape. Backed by five capable singer-songwriters and an unbeatable live act, the Grape combined Dead-like acid jamming with a three-guitar pop wall of sound that fused Beach Boys harmonies with blues and fingerpicking folk. With all the odds in their favour, the hopes of these young men were dashed by a level of managerial and commercial ineptitude that would be amusing if it weren’t so real.

Despite these career failures, Spence was still the same old Skippy: ‘a little Buddha’ genuinely committed to peace, love and the utopian ideals of hippiedom. Heading to New York to record their second album, Moby Grape and Skip could hardly have anticipated the changes to come.

Details are thin on what really went down in New York, but it seems that Skip started hanging around with a dodgy Aleister Crowley-style psychedelic cult. A female figure is a constant in the accounts of his bandmates: a never-identified “black witch” with whom, under the influence of “lots of psychedelics”, Skip began venerating a “70-year-old street guy they called ‘father’”. Yet the mind can only take so much. After what one can assume was one too many tastes of the occult-lysergic sacrament, Skip had a full-blown psychotic break. Believing himself to be the anti-Christ, he set off to murder his bandmate, drummer Don Stevenson, in his hotel room. Axe in hand and “sweating like a son of a gun”, Skip made quick work of the door before being forcefully restrained on the floor and arrested.

His life was never the same.

The one usual consolation of a bad psychedelic trip is that, no matter what the drug-ravaged mind supposes at the time, ‘it will end’. But Skip’s bad trip, which already sounds far worse than most, never really ended. His mind shattered, ravaged by delusions, hallucinations and persistent rumination on axe murder and divine judgement, he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and committed to the notorious Bellevue psychiatric hospital in New York, where he soon set to work.

One can only imagine the harrowing scenes in which Oar was born. Holed up in a sterilised, white-walled room and surrounded by maniacs, Skippy strummed and scribbled away under an oppressive chemical cocktail of anti-psychotics, anti-depressants, tranquilisers, downers and leapers. It’s surprising that he could even function at all. Thorazine, one of the drugs Skip was dosed with daily, has the famous side effect of the ‘Thorazine shuffle’: the unmistakeable, semi-stoned lurch made by psychotics and schizoids under its lethargic, analgesic spell.

On the face of it, then, it doesn’t sound surprising that Oar has gained a reputation for being ‘crazy music’. In fact, that’s exactly how his record label promoted it in a shameless advertising campaign in 1969. But the reality is far more subtle. Oar is not the rantings of a deranged lunatic, communicating nonsensically from the other side. Its lyrics generally make sense and, in places, show more insight (should I say sanity?) than most songwriters could ever dream of; its rhythms are certainly unusual, but they are ordered and stable; and its melodies, the gems of the album, are meticulously and beautifully constructed.

In fact, I would argue that Skip’s mental illness is not the defining theme of the album at all. More than a ‘soundtrack to schizophrenia’ as some critics have claimed, this album is instead a religiously-charged confession of sin, with Skip looking back at the incidents in New York with a remorse and penitence bordering on self-loathing. A fundamentally American record, in Oar Skip explores his influences from folk, country, blues and psychedelia to create a living document to the end of the ‘60s dream.

There’s something about the first ten seconds of Oar that I find irresistible. Skip prepares us for blast-off with a skeletal up-strum on the acoustic guitar and an elegant, dancing guitar phrase. And with a shot on the snare, Skip opens ‘Little Hands’ – a catchy, accessible prayer for world peace that (in some universe) could have been a chart hit. Despite mainly being built on a single Gb power chord, there is no monotony to this stellar track: behind off-beat marching-style drumming, Skip drives us through a utopic scene where the ‘little hands [are] clapping’, the ‘children are laughing’ and the ‘piper is piping’.

But having brought the song to life in the tragic corridors of an asylum, ‘Little Hands’ is a cause for both admiration and concern. On the one hand, it offers a glimpse into Skip’s unrelenting optimism, as he looks out to a hopeful future beyond the grim realities of psychosis. But ‘Little Hands’, and the psychedelic element of Oar in general, is in some ways quite disturbing. In continuing to give such a hippie-charged vision for the world, Skip is arguably lending his name to the very system that landed him in Bellevue in the first place. Indeed, by the end of the 1960s, the Love Generation and its undiscriminating evangelism for mind expansion had left in its wake a trail of acid casualties, dope addicts and a Nixon Presidency. In its own way, then, Oar is a self-defeating exposé of the philosophy that Skip himself championed.

‘War In Peace’, one of my favourites from the album, shows Skip continuing his quest into the inner mind. Powered by generously echoed guitar, drums and sibilant vocals, the whole track almost seems to be floating on a pulsing, gushing psychedelic wave. Over ‘Arnold Layne’-style descending chords and an unusually angular vocal melody, Skip’s lyrics tell an abstract sci-fi tale seemingly inspired by the Book of Revelation. Skip prophesies that the ‘war in peace’ will ‘come to separation’ and our ‘coronation’, adding an esoteric edge to the Tolstoy original. Revelling in his role as a psychedelic Nostradamus, Skip foresees that once the ‘funny combination’ has been divorced, we will no longer ‘rest in peace’: rather, draped ‘in red’, the ‘risen dead will cross another generation’ and ‘the cosmic federation’ will ‘see you clear’. On top of the fun (and slightly demented) lyricism, ‘War In Peace’ features some of Skip’s best lead guitar playing. Switching emphasis between the E and the A notes, his Jerry Garcia-style leads play on the ambiguity of its chord progression, perhaps reinforcing the precarious balance of the ‘war in peace’. In the outro, the wave peaks with echo-heavy sound effects sounding like laser guns and a strangely well-placed cover of Cream’s ‘Sunshine Of Your Love’: weird, but very effective.

But if you thought ‘War In Peace’ was strange, ‘Grey/Afro’ will sound like it’s from another planet. Unlike anything I’d really heard before, the track repels and attracts any attempt at categorisation. An entrancing exercise in minimalism, it sounds at once like the tribal soundtrack to an ayahuasca ceremony and a classic ‘60s raga, with a near-10-minute duel between tabla-style drums and woody, melodic bass. Content to ride on its own bizarre momentum, ‘Grey/Afro’ is a song that both goes nowhere and doesn’t need to go anywhere at the same time. Indeed, after the first few minutes, it becomes apparent that no key change is forthcoming. The listener is almost coerced into surrender as its vulnerable, improvised melodies track, consume and build into a continuous, integrated drone.

Skip’s words, which mix pre-written verse with paradoxical, semi-sensical ad-libs, convey ill-concealed feelings of romantic frustration. ‘[It] seems that every time I talk to you/You have something else to do’, Skip complains, before issuing his nihilistic rejection – ‘To be sure, I don’t give a damn/Live in a place, do anything’. Most interestingly, though, Skip’s improvisatory address to his lover contains a certain religious influence. ‘We’ll look at talk about how death is spread’, he sings. ‘Do you know you ask and you shall live/And die and you can turn to sin?’

After the incident in New York, sin was something that probably played on Skip’s mind a lot. With nothing to occupy him but the legacy of his own near-fatal error, it’s understandable that he would seek channels for reconciliation, repentance and healing. As for the religious language and symbology of his repentance, this perhaps stemmed from his song-writing explorations in blues and country, which are both intensely religious in their foundations.

Indeed, by this time returning to rock’s building blocks was all the rage amongst the musical elite. Just as quickly as they came, the kaftans, beads and LSD were dropped in favour of hard rock, blues riffs and raw live performance, with acts like The Rolling Stones, The Byrds and The Beatles all shifting back-to-basics by 1969. In his return, Skip shows himself to be a master of his own musical origins.

In fact, Skip’s country pieces are, for me, some of the finest of the era. When I close my eyes and listen to ‘Weighted Down’, I imagine Skip performing in a half-empty saloon. Perched on his stool under a dim, swaying light, his cutting, personal words are lost on an audience too drunk or depressed to pay attention. In a heavenly country waltz, Skip co-opts the imagery of classic southern tales to tell a parable seemingly about himself. ‘Weighted down by possessions, weighted down by the gun’, Skip sits by the river, fruitlessly anticipating the arrival of his estranged lover. Perhaps daydreaming on the world outside his asylum walls, Skip asks ‘whose socks [she] was darning/While [he’s] been gone away so long’. ‘Guilty of sin’, Skip’s absence is the ‘best thing for [her]’, according to his lover’s best friend. Amidst the pain of their separation and with an air of distant wisdom, Skip brings himself to confront her adultery: ‘I come with words of pain to bring you news of life/If you can’t find your woman, don’t take another’s wife’.

In ‘Cripple Creek’, Skip adds a Latin feel to a country classic. Behind strummed acoustic guitar and a deep, crooner baritone, Skip adds delicate samba acoustic fills and odd-accented hi-hat brushes. And where the original Kentucky tune ‘Cripple Creek’ is bawdy, upbeat and tongue-in-cheek, Skip’s update is dark and strangely poetic. In some of his best ever words, Skip tells the tale of a dying cripple and his seraphic adventures in the afterlife. Confined to his deathbed, the cripple is taken on a visionary ‘daydream’ ‘on a petal path’ and ‘past the streams of fire’. Having ‘left his wheelchair spinning deeper in the mud’ and been greeted by an angel, the cripple is confronted with ‘what was plain to see’: ‘his burden was himself’. Now dead and ‘gone for good’, he is tortured beyond the grave – he cannot ‘see his loved one like he thought he should’.

‘Books of Moses’, Skip’s brilliantly-executed foray into blues, is a true cotton-picking delta spiritual. Like some kind of acid-fried evangelical preacher, he takes the pulpit and delivers a sermon bursting with biblical and mythological imagery. ‘Heroes welcome, there stands your king’, Skip roars, ‘where the serpent shudders and the angels sing.’ Against a musique concrète backdrop of rainfall, thunderstorms, hammers and chisels, Skip’s drop-C blues riffing and Old Testament lyricism paint a scene of near-apocalyptic intensity.

For a change in pace, ‘Margaret/Tiger Rug’ shows Skip adopting the playful persona of a children’s entertainer. With an oompah rhythm, Willy Wonka instrumental breaks and audible chuckles, the track sounds like a Thorazine nursery rhyme. But, on closer inspection, the friendly Dr. Seuss exterior betrays an underlying mood of miserable self-reflection. Indeed, the tale of ‘Margaret, the daring songwriter’, sounds awfully lot like Skip himself. Like Margaret, he ‘had everything going for [him]’ – if not for that tragic, irreparable mistake, who knows how successful he would have been. ‘So, take a ride on her pen [and] step inside’ Skip insists, before describing her (and himself) as the ‘daring ice-skater’ that ‘skates the truth on the ice’. Now presumably in the ‘Tiger Rug’ section, he dons the guise of the psychiatric authorities that detained him – ‘It appears I sent you off to treatment/With the tiger by the tail’. A fly on the wall to his own incarceration, he describes the ‘stripes on him, like jail’ and the ‘jailer that comes in twice a day/And feeds him a hunk of meat/That’s just the same as you get out on the street’.

If this record does have a true light-hearted side, ‘Dixie Beach Promenade’ would be it. Flowing like an effortless southern breeze, the track is a bouncy country-and-western figure with some nice cascading drum fills and acoustic soloing. Skip probably had great fun writing this one. He winks and smirks away with a bawdy plea for ‘some bal for my lance and a little left for my hoochie cooch’. ‘I’ll stay by your side today’, Skip assures his girl, for ‘you’ll stay underneath me tonight’. With an audible grin, he pokes fun at hippie faddishness, with the ‘zen food’ that teaches him ‘how to think’ and the ‘yin for [his] yang that would make everything alright.’

Perhaps the most oblique song on the album, ‘Lawrence of Euphoria’ is a bizarre one-and-a-half-minute-long character piece. A half-hearted pun on ‘Lawrence of Arabia’, Skip’s alter-ego sounds like a rather strange fellow: ‘no more will you weep’ with Lawrence, as he’ll ‘come in your sleep’, ‘share your tent’ and even ‘pay your rent’. ‘Vivian from Oblivion’ and ‘Ellie-Mae from California’ are twin-sisters, and also seemingly prostitutes, of whom Lawrence is happy to make use.

But if you have any doubts about the depth of Skip’s pain, listen to ‘Diana’. Over a strained and sometimes hoarse vocal, ‘Diana’ is an impassioned expression of need without any hint of sarcasm, irony or sentimentality. A masterpiece in multi-tracking, the song is a delicate, dense web of interlocking guitars, bass and drums, with ascending harmonic strums, melodic acoustic riffs and emotive electric bends. Skip calls out in near-desperation, separated from his lover. ‘This is my heartbeat’, Skip declares, as if to affirm even his own basic humanity. ‘Oh, oh, Diana. I am in pain. Oh, oh, Diana. Tears fall like rain.’ It’s probably unintentional, but’s interesting that he chose such a name for his estranged woman. In Roman mythology, Diana is the divine mother, the feminine personification of nature and the supreme, wholly removed from mere mortal concerns – even, it seems, when that concern is a debilitating mental illness.

In ‘Broken Heart’, Skip is lost. For three and a half minutes, he delivers a haunting, ironic message of abject self-denial. In a dark and depressing litany, he lists all the trials and tribulations he’d rather endure than the judgement of the Lord. What’s most worrying is how he accepts these trials with such open-armed invitation: ‘a broken heart would be lovely’ and ‘a broken heart would satisfy, broken in a mess’, and ‘a severed eye would gratify my soul, I must confess’. Comparing himself to a ‘thirsty cowboy’ who ‘drowned himself to death’, Skip’s self-denial is all the more saddening when one considers his sheer promise as a musician. The guitar phrases are lyrical and unerringly melodic, and Skip’s voice is strong, commanding and pathetically vulnerable.

Having prostrated himself in front of the Lord, ‘All Come To Meet Her’ marks their ecstatic embrace. In the hymnal introduction, my favourite moment on all of Oar, Skip’s choral melody is supported by a warm, sophisticated guitar track that dances, glides and flows across the scale. Exploiting the rich ambiguity of western harmony, Skip’s chords blur major and minor into a mystic, unified whole, as if to represent the bliss of laboured salvation. ‘Amen’, he concludes. In the verses, Skip intones the title in an endless mantra-like recitation that grinds the terms into an artificial, meaningless dust: by the end, it simply doesn’t matter who the never-explained ‘her’ is.

There is a strange tendency in our culture to romanticise people like Skip. I’m certainly guilty of it myself. We like to see these casualties as almost like psychedelic Icaruses – truth-seekers who flew too close to the sun and ‘saw too much’. But such mythmaking tends to forget the lived reality of such an experience. Indeed, just as Icarus plummeted and died in a crushed heap, Skip soon drifted into a tortured life of hard drug abuse, homelessness and delirium. A far cry from the handsome, long-haired youth of Oar, by the time of his death at just 52 Skip looked like a dirty, haggard old man.

Next year, it will be fifty years since that young man’s album was first released. Luckily for Skip, though, those lucky few contained some big names. After years of indifference and neglect, the album finally started creeping out of the woodwork in the early 1990s. In 1999, More Oar, an Oar tribute album, was released just after Skip’s death, featuring appearances from famous friends like Robert Plant, Tom Waits and Beck.

As that lucky few grows year on year, one hopes that maybe (just maybe) Skip’s tragic life was worth all the pain.

– Ed Prideaux

© Copyright http://www.psychedelicbabymag.com/2018

Well-written review on one of the finest albums ever made. Good to see it featured here.